用于分配加固学习的对手纹状体电路

作者:Uchida, Naoshige

数据可用性

预处理数据已记录并可在Dryad上下载124。

代码可用性

本文中用于分析和生成所有数字的代码可在GitHub上获得125((https://github.com/alowet/distributionalrl)。

参考

Bellemare,M.G.,Dabney,W。&Rowland,M。分布强化学习(麻省理工学院出版社,2023年)。

舒尔茨(W.科学 275,1593年1599年(1997年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Dabney,W。等。基于多巴胺的增强学习中价值的分配代码。自然 577,671年675(2020)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Shin,J。H.,Kim,D。&Jung,M。W.背侧直接和间接途径中奖励和运动信息的差异编码。纳特。社区。 9,404(2018)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Nonomura,S。等。通过纹状体直接和间接途径监视和更新目标指导行为的动作选择。神经元 99,1302â1314.e5(2018)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Hikida,T.,Kimura,K.,Wada,N.,Funabiki,K。&Nakanishi,S。突触传播在直接和间接纹状体途径中的独特作用,以奖励和厌恶行为。神经元 66,896 - 907(2010)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Kravitz,A。V.,Tye,L。D.&Kreitzer,A。C.直接和间接途径纹状体神经元在增强中的不同作用。纳特。Neurosci。 15,816年818(2012)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Tai,L.-H.,Lee,A.M.,Benavidez,N.,Bonci,A。&Wilbrecht,L。纹状体神经元的不同亚群的瞬时刺激模仿动作值的变化。纳特。Neurosci。 15,1281年1289年(2012年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Cruz,B。F。等。动作抑制揭示了对手通过纹状体回路的平行控制。自然 607,521 - 526(2022)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Floresco,S。B.伏隔核:认知,情感和动作之间的接口。安努。Psychol牧师。 66,25年52(2015)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Sutton,R。S.&Barto,A。G.强化学习:简介卷。2(麻省理工学院出版社,2018年)。

Yagishita,S。等。多巴胺作用对树突状刺的结构可塑性的关键时间窗口。科学 345,1616年1620年(2014年)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Iino,Y。等。歧视学习和脊柱增大的多巴胺D2受体。自然 579,555 - 560(2020)。

Lee,S。J。等。多巴胺在学习中对PKA的细胞型特异性异步调节。自然 590,451 - 456(2021)。

Ito,M。&Doya,K。在固定和自由选择任务期间,纹状体的背外侧,背侧和腹侧部分的明显神经表示。J. Neurosci。 35,3499 3514(2015)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Shin,E。J.等。鲁棒和分布的动作值的神经表示。Elife 10,E53045(2021)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Hattori,R.,Danskin,B.,Babic,Z.,Mlynaryk,N。&Komiyama,T。学习过程中历史依赖性价值编码的区域特异性和可塑性。细胞 177,1858年1872.E15(2019)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Hirokawa,J.,Vaughan,A.,Masset,P.,Ott,T。&Kepecs,A。额叶皮层神经元类型分类编码单个决策变量。自然 576,446 451(2019)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Otterheimer,D.J.,Hjort,M.M.,Bowen,A.J.,Steinmetz,N。A.&Stuber,G。D.奖励学习过程中小鼠皮层中提示值的稳定的分布式代码。Elife 12,RP84604(2023)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Watabe-uchida,M。&Uchida,N。多巴胺系统:多巴胺的WEAL和WOE。冷泉港。SYMP。量子。生物。 83,83 - 95(2018)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

De Jong,J。W。等。一种用于编码中左右多巴胺系统中厌恶刺激的神经回路机制。神经元 101,133â151.e7(2019)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Tsutsui-Kimura,I。Et。在决策任务中,纹状体三个区域中多巴胺轴突中的不同时间差异信号。Elife 9,E62390(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Engelhard,B。等。VTA多巴胺神经元中感觉,运动和认知变量的专门编码。自然 570,509 - 513(2019)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Akiti,K。等。纹状体多巴胺解释了新颖性引起的行为动态和威胁预测的个体变异性。神经元 110,3789 3804.e9(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Lee,R。S.,Sagiv,Y.,Engelhard,B.,Witten,I。B.&Daw,N。D.特定特定的预测错误模型解释了多巴胺能异质性。纳特。Neurosci。27,1574年1586年(2024年)。Jeong,H。等。

中唇多巴胺释放传达了因果关系。科学 378,EABQ6740(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Coddington,L。T.,Lindo,S。E.&Dudman,J。T. Mesolimbic多巴胺适应了从动作中学习的速度。自然 614,294 302(2023)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

科斯塔(V.神经元 92,505 -517(2016)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

St Onge,J。R.&Floresco,S。B.基于风险的决策的多巴胺能调节。神经心理药理学 34,681 - 697(2009)。

文章一个 Google Scholar一个

Zalocusky,K。A.等。伏隔核D2R细胞发出了先前结果并控制风险决策。自然 531,642 - 646(2016)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Ma,W。J.,Beck,J。M.,Latham,P。E.&Pouget,A。Bayesian用概率人口代码推断。纳特。Neurosci。 9,1432 - 1438(2006)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Walker,E。Y.等。研究不确定性的神经表示。纳特。Neurosci。 26,1857年1867年(2023年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Bellemare,M。G.,Dabney,W。&Munos,R。强化学习的分布观点。在Proc。第34届机器学习国际会议(Eds Precup,D。&Teh,Y。W.)449 458(PMLR,2017年)。

Wurman,P。R.等。凭借深厚的加强学习使冠军冠军冠军司机。自然 602,223 - 228(2022)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Rothenhoefer,K。M.,Hong,T.,Alikaya,A。&Stauffer,W。R.稀有奖励放大了多巴胺反应。纳特。Neurosci。 24,465 - 469(2021)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Avvisati,R。等。中脑多巴胺神经元离散群体中关联学习的分布编码。细胞代表。 43,114080(2024)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Sousa,M.,Bujalski,P.,Cruz,B。F.,Louie,K。&Paton,J。J. Dopamine神经元编码了未来奖励的多维概率图。预印本Biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.12.566727(2023)。

Muller,T。H.等。前额叶皮层中的分布增强学习。纳特。Neurosci。27,403 408(2024)。Rowland,M。等。

分配加固学习中的统计和样本。在Proc。第36届机器学习国际会议(Eds Chaudhuri,K。&Salakhutdinov,R。)5528 -5536(PMLR,2019年)。

Tano,P。,Dayan,P。&Pouget,A。分布强化学习的本地时间差异代码。在Proc。神经信息处理系统的进步33(Eds Larochelle,H。等人)13662 13673(Neurips,2020)。

Louie,K。通过归一化强化学习进行非对称和自适应奖励编码。PLOS计算。生物。 18,E1010350(2022)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Schã¼tt,H。H.,Kim,D。&Ma,W。J.奖励预测错误神经元实现了有效的奖励代码。纳特。Neurosci。 27,1333年1339(2024)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

OâNeill,M。&Schultz,W。Orbitrontal神经元对奖励风险的编码大多与奖励价值编码不同。神经元 68,789年800(2010)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Monosov,I。E.&Hikosaka,O。灵长类动物前隔膜区域神经元的奖励不确定性的选择性和分级编码。纳特。Neurosci。 16,756 - 762(2013)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

怀特(J. K.纳特。社区。 7,12735(2016)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Yanike,M。&Ferrera,V。P.前尾状核中结果风险和作用的表示。J. Neurosci。 34,3279 3290(2014)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Yamada,K。&Toda,K。小鼠的瞳孔动态执行帕夫洛维亚延迟调节任务反映了奖励预测的信号。正面。系统。Neurosci。 16,1045764(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Tian,J。等。在多巴胺神经元的单突触输入中分布和混合信息。神经元 91,1374年1389(2016)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Stringer,C。等。自发行为驱动多维,全心全意的活动。科学 364,255(2019)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Musall,S.,Kaufman,M。T.,Juavinett,A。L.,Gluf,S。&Churchland,A。K.单审神经动力学以丰富的运动为主。纳特。Neurosci。 22,1677年1686年(2019年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Hoyer,P。&Hyvérinen,A。将神经反应变异性解释为后部的蒙特卡洛采样。在Proc。 神经信息处理系统的进步15(Eds Becker,S。等人)293 300(麻省理工学院出版社,2002年)。

Orbân,G.,Berkes,P.,Fiser,J。&Lengyel,M。视觉皮层中基于神经变异性和基于抽样的概率表示。神经元 92,530 543(2016)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Bernardi,S。等。海马和前额叶皮层中抽象的几何形状。细胞 183,954 - 967.E21(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Lowet,A。S.,Zheng,Q.,Matias,S.,Dugnowitsch,J。&Uchida,N。大脑中的分布强化学习。趋势神经科学。 43,980â997(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Gerfen,C。R.&Surmeier,D。J.多巴胺对纹状体投影系统的调节。安努。Neurosci牧师。 34,441â466(2011)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

浮士德(T. W.+在动机方法中神经元。预印本Biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.09.02.556060(2023)。

N. Martiros,V. Kapoor,Kim,S。E.&Murthy,V。N. D1和D2神经元在腹侧纹状体的嗅觉结节中通过D1和D2神经元的明显表示。Elife 11,E75463(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Nishioka,T。等。伏隔核中与误差相关的信号传导D2受体表达神经元指导小鼠基于抑制作用的选择。纳特。社区。 14,2284(2023)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Kupchik,Y。M.等。通过D1和D2受体编码直接/间接途径对于伏隔的预测无效。纳特。Neurosci。 18,1230年1232(2015)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

这样,F。P.等。ATARI模型动物园,用于分析,可视化和比较深钢筋学习剂。在Proc。第28届国际人工智能会议(Kraus,S。)3260â3267(IJCAI,2019年)。

Collins,A。G. E.&Frank,M。J.对手Actor学习(OPAL):纹状体多巴胺对增强学习和选择激励的互动效果进行建模。Psychol。修订版 121,337â366(2014)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Gjorgjieva,J。,Sompolinsky,H。&Meister,M。感觉编码中的途径分裂的好处。J. Neurosci。 34,12127年12144(2014)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Ichinose,T。&Habib,S。视网膜和视觉系统中的开关信号通路。正面。眼科。 2,989002(2022)。

文章一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Poulin,J.-F.,Gaertner,Z.,Moreno-Ramos,O。A.&Awatramani,R。使用单细胞基因表达分析方法对中脑多巴胺神经元进行分类。趋势神经科学。 43,155â169(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Wenliang,L。K.等。分销钟力杆操作员对平均嵌入式。在Proc。第41届机器学习国际会议(Eds Salakhutdinov,R。等人)52839 52868(PMLR,2024)。

Mikhael,J。G.&Bogacz,R。基底神经节中的学习奖励不确定性。PLOS计算。生物。 12,E1005062(2016)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Cui,G。等。在作用启动过程中,纹状体直接和间接途径的同时激活。自然 494,238 - 242(2013)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Markowitz,J。E.等。纹状体通过时刻的动作选择组织3D行为。细胞 174,44 -58(2018)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Tan,B。等。通用中唇神经合奏对饥饿和口渴的动态处理。Proc。纳特学院。科学。美国 119,E2211688119(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Bar-Gad,I.,Morris,G。&Bergman,H。基底神经节中的信息处理,降低维度和增强性学习。prog。神经生物醇。 71,439 473(2003)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Barth-Maron,G。等。分布式分配确定性政策梯度。在Proc。第六届学习代表国际会议4855â4870(ICLR,2018年)。

Brown,V。M.等。认知行为疗法后,抑郁症和对症状变化敏感性敏感性的人的强化学习中断。贾玛精神病学 78,1113年1122(2021)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Gueguen,M。C. M.,Schweitzer,E。M.&Konova,A。B.成瘾中强化学习和决策的计算理论驱动的研究:我们学到了什么?Curr。意见。行为。科学。 38,40 - 48(2021)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Paxinos,G。&Franklin,K。B. J.Paxinos和Franklin的鼠标大脑在立体定位坐标中(学术出版社,2019年)。

Gong,S。等。基于细菌人造染色体的中枢神经系统的基因表达图集。自然 425,917â925(2003)。

Gong,S。等。将CRE重组酶靶向具有细菌人造染色体构建体的特定神经元群体。J. Neurosci。 27,9817年9823(2007)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Gerfen,C。R.,Paletzki,R。&Heintz,N。Gensat BAC Cre-Recombinase驱动线研究脑皮质和基底神经节电路的功能组织。神经元 80,1368年1383(2013)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Govorunova,E。G.,Sineshchekov,O。A.,Janz,R.,Liu,X。&Spudich,J。L.自然光门控阴离子通道:一种用于晚期光遗传学的微生物风光蛋白家族。科学 349,647 - 650(2015)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Li,N。等。皮质回路中光遗传学失活的时空约束。Elife 8,E48622(2019)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

科恩(J.自然 482,85 -88(2012)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Thiele,S。L.,Warre,R。&Nash,J。E.帕金森氏病的单方面赋予的6-OHDA小鼠模型的开发。J. Vis。经验。60,E3234(2012)。Dana,H。等。

高性能钙传感器,用于神经元种群和微室内成像活性。纳特。方法 16,649 657(2019)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Klapoetke,N。C.等。独立的神经种群的独立光学激发。纳特。方法 11,338â346(2014)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Lee,J。&Sabatini,B。L.纹状体间接途径通过碰撞竞争介导探索。自然 599,645â649(2021)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Uchida,N。&Mainen,Z。F.大鼠嗅觉歧视的速度和准确性。纳特。Neurosci。 6,1224年1229(2003)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Pavlov,I。P。条件反射:研究大脑皮质的生理活性(牛津大学出版社,1927年)。

Jun,J。J。等。完全集成的硅探针,用于高密度的神经活动记录。自然 551,232â236(2017)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Steinmetz,N。A.等。Neuropixels 2.0:用于稳定的长期大脑记录的微型高密度探针。科学 372,EABF4588(2021)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Pachitariu,M.,Sridhar,S.,Pennington,J。&Stringer,C。Spike与Kilosort4。纳特。方法 21,914â921(2024)。

Zhou,Z。C.等。行为过程中神经动力学的深脑光学记录。神经元 111,3716 3738(2023)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Pachitariu,M。等。Suite2p:超过10,000个具有标准两光子显微镜的神经元。预印本Biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/061507(2017)。

弗里德里希(J.PLOS计算。生物。 13,E1005423(2017)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Lopes,G。等。盆景:基于事件的处理和控制数据流的框架。正面。神经信息。 9,7(2015)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Pisanello,M。等。通过在锥形光纤中的模态消散来定制光遗传学。科学。代表。 8,4467(2018)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Lee,J.,Wang,W。&Sabatini,B。L.解剖学上隔离的基底神经节途径允许平行行为调制。纳特。Neurosci。 23,1388年1398(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Sanders,J。I.&Kepecs,A。一种用于生理和行为的低成本可编程脉冲发生器。正面。神经。 7,43(2014)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Shamash,P.,Carandini,M.,Harris,K。&Steinmetz,N。一种用于分析Slice组织学的电极轨道的工具。预印本Biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/447995(2018)。

Wang,Q。等。艾伦小鼠脑公共坐标框架:3D参考地图集。细胞 181,936 - 953.E20(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Claudi,F。等。用脑生产者可视化解剖注册的数据。Elife 10,E65751(2021)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Chon,U.,Vanselow,D。J.,Cheng,K。C.&Kim,Y。对常见小鼠脑图集的增强和统一的解剖标记。纳特。社区。 10,5067(2019)。

文章一个 广告一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Claudi,F。等。Brainglobe Atlas API:神经解剖图谱的常见界面。J.开源软件。 5,2668(2020)。

文章一个 广告一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Hintiryan,H。等。鼠标皮质 - 纹状体projectome。纳特。Neurosci。 19,1100 A114(2016)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Peters,A。J.,Fabre,J。M. J.,Steinmetz,N。A.,Harris,K。D.&Carandini,M。纹状体活动在地形上反映了皮质活性。自然 591,420â425(2021)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Harris,C。R.等。带有numpy的数组编程。自然 585,357 362(2020)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Virtanen,P。等。Scipy 1.0:Python中科学计算的基本算法。纳特。方法 17,261 272(2020)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

McKinney,W。Python中统计计算的数据结构。在Proc。第9 python在科学会议上(Eds van der Walt,S。&Millman,J。)56â61(Scipy,2010年)。

Buitinck,L。等。机器学习软件的API设计:Scikit-Learn项目的体验。在Proc。ECML PKDD研讨会:数据挖掘和机器学习的语言(edscré©Milleeux,B。等人)108 -122(ECML PKDD,2013年)。

Seabold,S。&Perktold,J。StatsModels:Python的计量经济学和统计建模。在Proc。第9 python在科学会议上(Eds van der Walt,S。&Millman,J。)92â96(Scipy,2010年)。

Hunter,J。D. Matplotlib:2D图形环境。计算。科学。工程。 9,90 -95(2007)。

文章一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Waskom,M。Seaborn:统计数据可视化。J.开源软件。 6,3021(2021)。

文章一个 广告一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Dietterich,T。G.比较监督分类学习算法的近似统计检验。神经计算。 10,1895年1923年(1998年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

枕头,J。W。等。完整神经元种群中的时空相关性和视觉信号传导。自然 454,995 999(2008)。

文章一个 广告一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Yuan,M。&Lin,Y。具有分组变量回归中的模型选择和估计。J. R. Stat。Soc。系列B Stat。methodol。 68,49 - 67(2006)。

文章一个 MathScinet一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Tseng,S.-Y.,Chettih,S.N.,Arlt,C.,Barroso-Luque,R。&Harvey,C。D.在跨后皮质区域共享和专门编码,以进行动态导航决策。神经元 110,2484 2502.E16(2022)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Churchland,M。M.等。刺激发作淬灭神经变异性:一种广泛的皮质现象。纳特。Neurosci。 13,369 378(2010)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Eshel,N.,Tian,J.,Bukwich,M。&Uchida,N。多巴胺神经元具有共同的响应功能,以获得奖励预测错误。纳特。Neurosci。 19,479 486(2016)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Rescorla,R。A.&Wagner,A。R. in经典条件II:当前的研究和理论(Eds Black,A。H.&Prokasy,W。F.)64â99(Appleton-Century-Crofts,1972)。

Gurney,K。N.,Humphries,M。D.&Redgrave,P。Cortico-Striatal可塑性的新框架:行为理论在强化动作界面上符合体外数据。Plos Biol。 13,E1002034(2015)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

莱斯(M. E.)和克拉格(M. E.脑部。修订版 58,303 313(2008)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

德雷尔(J.J. Neurosci。 30,14273年14283(2010年)。

文章一个 CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Dabney,W.,Rowland,M.,Bellemare,M。&Munos,R。分数回归的分布强化学习。在Proc。第32届AAAI人工智能会议(Eds McIlraith,S。A.&Weinberger,K。Q.)2892 2901(AAAI出版社,2018年)。

Huber,P。J.位置参数的强大估计。安。数学。统计 35,73 - 101(1964)。

文章一个 MathScinet一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Romero Pinto,S。&Uchida,N。补品多巴胺和价值学习中的偏见通过生物学启发的增强学习模型相关联。预印本Biorxiv https://doi.org/10.1101/2023.11.10.566580(2023)。

Lowet,A。S。等。数据来自:用于分配加固学习的对手纹状体电路。dryad https://doi.org/10.5061/dryad.80GB5MM0M(2024)。

Lowet,A。S. Alowet/DistributionAlrl:出版物就绪版本(v1.0.2)。Zenodo https://doi.org/10.5281/Zenodo.14554845(2024)。

Chandak,Y。等。通用的非政策评估。在Proc。神经信息处理系统的进步34(Eds Ranzato,M。等人)27475 27490(Neurips,2021)。

Gagne,C。&Dayan,P。危险,审慎和计划是风险,避免和担忧。J. Math。Psychol。 106,102617(2022)。

文章一个 MathScinet一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Rockafellar,R。T.&Uryasev,S。有条件值的风险优化。J.风险 2,21 - 41(2000)。

文章一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

Fiser,J.,Berkes,P。,Orbãn,G。&Lengyel,M。统计学上最佳的感知和学习:从行为到神经表征。趋势Cogn。科学。 14,119 - 130(2010)。

文章一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 数学一个 Google Scholar一个

致谢

我们感谢Uchida实验室成员对手稿的宝贵讨论和评论;E. Soucy和B. Graham为仪器提供关键的帮助;A. Girasole和B. sabatini共享GTACR1小鼠系;X. Cai,B。Sabatini,C。Harvey和S.J. Gershman有用的对话;以及M. Carandini,K。D。Harris,A。J。Peters和Cortex Laboratory的其他成员,以了解有关Neuropixels记录的建议。这项工作得到了美国国立卫生研究院的赠款(R01NS116753至N.U.和J.D.和J.D.和F31NS124095 to A.S.L.)研究基金会(Narsad Young研究者第30035号至S.M.)。我们感谢哈佛大学生物成像中心(RRID:SCR_018673)的基础架构和对离体成像的支持,该基础架构由Simmons Award(授予A.S.L.)部分资助。本文中的计算部分是在哈佛大学的FAS科学研究计算小组支持的FASRC炮集群上进行的。

道德声明

竞争利益

作者没有宣称没有竞争利益。

同行评审

同行评审信息

自然感谢Ilya Monosov,Blake Richards和其他匿名,评论者对这项工作的同行评审的贡献。同行评审者报告可用。

附加信息

出版商的注释关于已发表的地图和机构隶属关系中的管辖权主张,Springer自然仍然是中立的。

扩展数据图和表

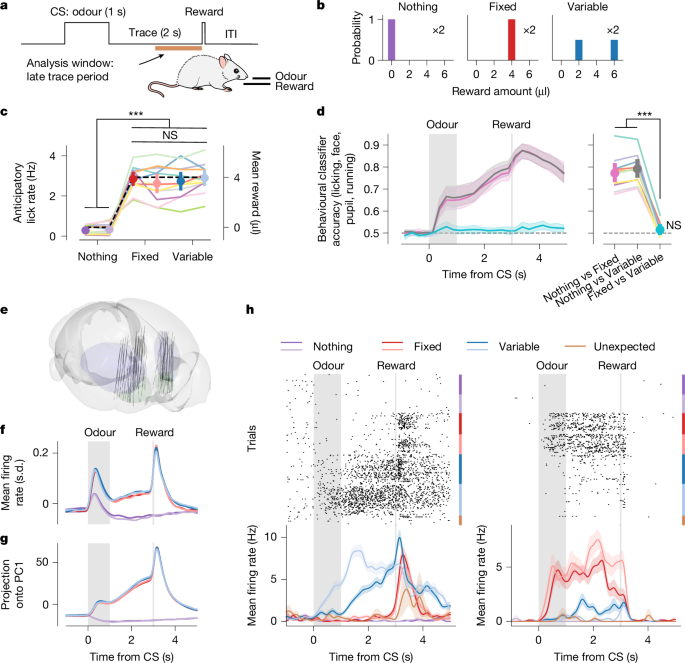

扩展数据图1附加行为分析。一个

,在面板中进行行为分类分析的示意图be。对应于同一分布的气味被视为同一类。这是针对固定与可变odour分类的情况进行说明的,背景阴影(黄色与灰色)指示分类器的目标。b,行为分类的示意图。在每个验证折叠上,搅拌,跑步,瞳孔区域,舔和训练集中的前50个面部运动能量PC被z键s缩放,然后通过线性内核传递到支持向量分类器(SVC),这可以预测关联的分配。c,正交分析的示意图。SVC学到的权重定义了最能最能分离分布的超平面的矢量正交。可以通过将每个试验的平均奖励(价值方向)对相应的行为回归变量进行回归来定义单独的向量。尽管SVC超平面一次仅考虑四个气味,但回归方向考虑了所有六种气味。d,分类器重量向量与值方向之间的余弦相似性。固定试验和可变试验之间的行为上的任何差异都是正交的价值(相对于0:0的机会水平:p<<0.001,没有固定,p<<0.001,没有任何变量,p=固定与变量的0.154)。e,在示例会话中对应于面对运动能量PC的空间掩模,并用方差排序。连续的PC强调了鼠标搅拌,嗅探和舔行为的更精细方面。f,晚期痕量和基线之间的舔率差异(在气味发作前1)对所有试验类型都显着,包括两种无异味的基线降低(所有)pS <0.001)。g,根据先前的气味试验是否导致2或6â¼l的奖励,可变气味的预期舔率没有差异(p= 0.179)。h,经过培训的线性分类器预测给定气味的先前变量试验中提供的奖励量的偶然准确性为50%(p= 0.326)。扩展数据图2值,RPE,气味和风险编码在整个纹状体上。

一个

,串行冠状切片显示探针插入的记录位点(白色虚线),记录在Allen Common Coartial坐标框架上。b,,,,顶部,热图显示了每个神经元的每种气味的平均Z得分发射速率。按照峰值活性的时间进行分类,当时在2个可变的2个气味试验中平均,然后按照相同的顺序绘制了以试验类型分组的其余试验。第七个也是最后一次试验类型对应于意外的奖励,而这些奖励之前没有气味。底部,所有神经元的平均Z得分射击率。c,与平均奖励显着相关的神经元的一部分,在非重叠的250(250 MS时箱)中分别计算出来。每只小鼠以不同的颜色显示,平均±95%c.i。跨黑色显示的小鼠。虚线是在将气味和分布之间的映射改组后的小鼠的平均值,从而考虑了纯气味编码。d,在痕量后期,重要细胞的平均百分比(p<<0.001)。e,,,,左边,交叉验证r2预测每个试验中的平均奖励是纹状体子区域的函数,在非重叠的250 ms时箱中分别计算出来。为了确保各个区域之间的公平比较,对于每只动物,我们通过反复采样而无需替换神经亚群,直到剩下的神经元少于40个神经元,而无需替换神经亚群来产生多个40个神经元的伪群。在给定区域中,神经元少于40的动物被排除在外。线显示每个子区域跨小鼠的平均值。正确的, 平均的r2在痕量后期。较小的点显示,该区域中至少有40个神经元的每只小鼠跨伪群的平均值。f,与c,除了显示与奖励预测误差(RPE)显着相关的神经元的比例,该神经元被定义为实际奖励和预期奖励之间的差异。g,与d,除了显示结果期间重要细胞的平均百分比,奖励交付后0(0p<<0.001)。h,将与平均值和RPE显着相关的每只小鼠中细胞的实际分数与平均分数和RPE编码细胞的单个分数的乘积进行了比较(假定独立性的预测分数;p<<0.001)。我,,,,左边,在多项式逻辑回归分类器解码气味身份的时间的时间内解码精度(虚线= 1/6的机会水平)。正确的,量化气味分类准确性(气味期)(p相对于机会水平,<0.001)。j,在气味期间的气味解码的混淆矩阵显示出所有气味的高解码精度,对于具有相同平均值的气味,相对较高的混淆性。k,跨阶时解码显示,气味解码在时间范围内是稳定的,允许训练有素的分类器,例如在痕量后期的活动中,将概念概述到偶然时期的气味时期,反之亦然(所有人都p相对于1/6的机会水平,S <0.001)。l,伪造的气味跨区域解码(见 方法题为跨区域,半球和基因型的比较。OT,嗅觉结节;副总裁,腹侧颗粒;MacBSH,伏伏壳中部核;LACBSH,外侧核伏壳;核心,伏隔核;VM,腹侧纹状体;VLS,腹外侧纹状体;DMS,背侧纹状体;DLS,背外侧纹状体(n= Macbsh的1鼠p= VM的0.006,所有其他pS <0.001)。m,与c,除了显示与每次bin的平均奖励编码的贡献后,除了与方差显着相关的神经元的分数外。n,在痕量后期晚期,显着残留方差单元的平均百分比为较少的比单独的气味编码所预测的p<<0.001)。o,明显少于偶然的正面和负差异的神经元对剩余方差进行编码(正和负面)pS <0.001)。p-r,与M-O,但对于有条件的价值(CVAR),这是一种用于金融和增强学习中的常见风险措施126,,,,127,,,,128,定义为较低内的期望值± - 概率分布的定量。对于我们的分布,这将等同于均值±> 0.5,相当于最低值±<0.5,仅针对变量分布而有所不同,其中是2。后者是我们在回归平均编码后在这里绘制的。同样,残留的CVAR细胞比单独的气味编码所预期的要少(p<<0.001),对于阳性和负编码细胞都是如此(均为pS <0.001)。扩展数据图3分布编码是强大的,正交对价值,并且在时间上保持一致。一个

,成对解码分析的示意图。

对线性SVC进行了单个固定和可变气味的培训,一次是两个。This resulted in six possible dichotomies, four of which encompassed one Fixed and one Variable odour (green arrows; “Across distributionâ€) and two of which compared odours cuing the same exact distribution (orange arrows; “Within distributionâ€).b, Pairwise decoding during the late trace period was significantly better for across- than within-distribution pairs, consistent with distributional but not traditional RL (p = 0.001).c, Schematic of congruency analysis, which considered all four Fixed and Variable odours simultaneously. In the Congruent grouping, both Fixed odours were assigned to one class (yellow background) and both Variable odours were assigned to the other class (grey background), just as was done for behavioral decoding. By contrast, in the Incongruent groupings, class assignments cut across Fixed and Variable distributions.d, Classifier accuracy in the late trace period was higher for Congruent than Incongruent pairs, again consistent with distributional but not traditional RL (Congruent:p = 0.028 vs. Incongruent 1,p < 0.001 vs. Incongruent 2).e, Schematic illustrating the classifier weight vector (normal to the separating hyperplane for across- or within-distribution classifications) and the regression weight vector (for Value or Variance).f, Quantification of cosine similarity between the classifier weight vector and the Value direction shows that the vectors are not significantly different from orthogonal (CCGP:p = 0.071 cosine similarity relative to chance value of 0; Pairwise:p = 0.797 Across- vs. Within-distribution absolute cosine similarity; Congruency:p = 0.493 Across- vs. Within-distribution absolute cosine similarity).g, Same asf, but for Variance rather than Value direction (p < 0.001 for all comparisons).h-j, Cross-temporal decoding for the pairwise, congruency, and CCGP analyses. Distributional RL is favored during every time period between odour onset and reward delivery, and decoders trained during one period almost always generalize to other time periods.Extended Data Fig. 4 A distribution-coding subpopulation is over-represented in the lAcbSh and permits ANN-based distribution decoding.一个, Pseudo-population CCGP across subregions (relative to chance level of 0.5:p

= 0.059, 0.473, 0.044, 0.017, 0.088, 0.346, 0.257, 0.407, and 0.133 for OT, VP, mAcbSh, lAcbSh, core, VMS, VLS, DMS, and DLS, respectively. Same order applies to all statistics in this figure). Pseudo-populations were constructed as in Extended Data Fig.

2l。b, Pseudo-population pairwise decoding across subregions (Across- vs. Within-distribution:p = 0.861, 0.344, 0.883, 0.010, 0.409, 0.040, 0.882, 0.482, 0.106).c, Pseudo-population congruency analysis across subregions (Congruent vs. Incongruent 1:p = 0.097, 0.817, 0.744, 0.007, 0.832, 0.047, 0.523, 0.138, 0.523; Congruent vs. Incongruent 2:p = 0.306, 0.760, 0.815, 0.010, 0.473, 0.177, 0.316, 0.486, 0.985).d, Parallelism score across subregions (relative to chance level of 0:p = 0.300, 0.878, 1.00, 0.001, 0.229, 0.243, 0.273, 0.615, 0.764).e,,,,左边, fraction of neurons with classifier coefficients above the percentile cutoff for all three (CCGP, pairwise, and congruency) analyses. Horizontal dotted line indicates level at which 2.5% of null coefficients fell above the cutoff; this was the 73rd percentile (vertical dotted line), and retained 11.43% of neurons.正确的, ratio of data to null coefficients falling above the cutoff (log scale).f, Fraction of distribution-coding cells in each subregion. This fraction is significantly higher in the lAcbSh than in more dorsal subregions (relative to lAcbSh:p = 0.339, 0.285, 0.473, 0.274, 0.071, 0.038, 0.001 for OT, VP, mAcbSh, core, VMS, VLS, and DLS, respectively;p < 0.001 for DMS).g, ANN schematic. Single-trial spike counts from the distribution-coding subpopulation一个were linearly mapped into 16 dimensions by the trainable matrixwand then fed through the network (see 方法)。After a final layer, a softmax function transformed activations into a properly-normalized probability distribution, whose 1-Wasserstein distance to ground truth was minimized with stochastic gradient descent.h, Example decoded distributions from the test set, shown as line plots to distinguish individual pseudo-trials.我, Wasserstein distance relative to reference for the ANN trained on all six trial types, with and without shuffling odour-distribution mappings (p < 0.001 ordered vs. shuffled;p < 0.001 ordered relative to chance value of 1;p = 0.350 shuffled relative to chance value of 1).j, Same as我, but for ANN trained on only the rewarded odours, which shared the same mean (p < 0.001 ordered vs. shuffled, ordered relative to chance value of 1, and shuffled relative to chance value of 1).k, Schematic depicting setup for transfer analysis.Four trial types, including both Nothing odours, were used for training (green background), and the other two were used for testing (orange background).Matched pairings veridically assigned odours to distributions, while mismatched pairings used either only Fixed or only Variable odours for training while assigning one member per training pair and one member per testing pair to the opposite distribution (indicated by the exclamation mark).There were four possible ways to draw the matched dichotomies, all of which are shown (rows).For the mismatched dichotomies, the distributions (Fixed or Variable) could be arbitrarily assigned to both pairs of red and blue odors, and then either red or blue could be assigned to the training versus test set, so only four of the eight total possibilities are显示。l, Wasserstein distance relative to reference for standard (mean ± s.e.m. = 0.128 ± 0.019), matched (0.217 ± 0.032), and mismatched (1.028 ± 0.123) settings. Standard is identical to analysis shown inc, except that for this decoder, neurons from all mice were pooled. Matched transfer yields distributions that are nearly as accurate as training with all six trial types (p < 0.001 for matched vs. mismatched and standard vs. mismatched, Student’st-test for independent samples;p = 0.043 for standard vs. matched, Student’st-test for independent samples;p < 0.001 for standard and matched relative to chance value of 1, one-sample Student’st-测试;p = 0.836 for mismatched relative to chance value of 1, one-sample Student’st-测试)。Extended Data Fig. 5 A generalized linear model (GLM) to examine trial history, reward, reward prediction, and motor encoding in the striatum.一个, Schematic illustrating the design of the GLM (see 方法)。Briefly, trial-length regressors (time in trial and trial history) were broken up into 7 raised cosine basis functions tiling the 6 seconds of each (odour-cued) trial.Reward, reward prediction, and sensory regressors were time-locked to reward or odour onset and then convolved with a logarithmically-scaled raised cosine basis112。Licking, whisking, and running regressors were convolved with the same basis in both the forward and reverse directions.Pupil area and face motion SVDs from Facemap were input directly to the model without convolving.

The Poisson GLM computes the sum of the regressors weighted by their fitted coefficients, passes this through an exponential nonlinearity, and uses this rate to predict spike counts in 20 ms bins.

b,,,,顶部, example regressor matrix for 10 test trials. Each row corresponds to a different predictor, binned on the left by regressor type (rectangles) and group (colour). Rectangles on top demarcate different trials, coloured by trial type.中间, empirical spike counts in each bin for an example neuron.底部, smoothed empirical firing rate (black) and model prediction (pink) for the trials shown. Deviance statistics in every panel of this figure rely on a held-out test set (never used during cross-validation), after zeroing out the contribution of electrode drift.c, Histogram of fraction deviance explained for all neurons.d, Fraction deviance explained as a function of striatal subregion (relative to DLS:p < 0.001 for OT, VP, lAcbSh, and core;p = 0.490, 0.608, 0.054 for VMS, VLS, and DMS, respectively). For these analyses, mAcbSh was omitted due to lack of neurons/animals.e, Difference in fraction deviance explained between the full model and reduced models in which trial history (上排), 报酬 (第二行), sensory and reward-prediction (third row), or motor (bottom row) regressors were excluded before re-fitting.f, Kernel strength (see 方法) of trial history (顶部), 报酬 (第二) expectile (第三), and motor (底部) regressors.g,如e, but showing the difference in fraction deviance explained as a function of striatal subregion. (History, relative to DLS:p = 0.124 for DMS;p < 0.001 for all other subregions; Reward, relative to DLS:p = 0.009, 0.141, and 0.441 for OT, VP, and DMS, respectively;p < 0.001 for all other subregions; Expectiles, relative to DLS:p = 0.234 for DMS;p < 0.001 for all other subregions; Motor, relative to DLS:p < 0.001 for all subregions).h,如f, but showing the kernel strength computed on the full model as a function of striatal subregion. (History, relative to DLS:p < 0.001 for OT, VP, and VLS;p = 0.042, 0.288, 0.023, and 0.926 for lAcbSh, core, VMS, and DMS, respectively; Reward, relative to DLS: 0.148, 0.004, 0.172 for VP, core, and DMS;p < 0.001 for all other subregions; Expectiles, relative to DLS:p < 0.001 for OT, VP, lAcbSh, VMS, and VLS;p = 0.285 and 0.014 for core and DMS, respectively; Motor, relative to DLS:p = 0.004 for DMS;p < 0.001 for all other subregions).我, Pearson correlation (across-neurons, within-sessions) of difference in deviance explained between reduced models. Holding out trial history, reward, or expectiles tends to similarly affect deviance for a given neuron, while being uncorrelated with motor behavior. Small dots, individual sessions; medium dots, mean across sessions within animals; large dots, mean ± 95% c.i. across mice. (Drop History vs. Drop Reward, Drop History vs. Drop Expectiles, and Drop Reward vs. Drop Expectiles,p < 0.001 for all subregions; Drop Motor vs. Drop History,p = 0.644, 0.479, 0.993, 0.428, 0.133, 0.148, 0.674, 0.986 for OT, VP, lAcbSh, core, VMS, VLS, DMS, and DLS respectively; Drop Motor vs. Drop Reward,p = 0.626, 0.981, 0.134, 0.596, 0.473, 0.028, 0.745, 0.498; Drop Motor vs. Drop Expectiles,p = 0.331, 0.816, 0.796, 0.681, 0.193, 0.603, 0.148, 0.554).Extended Data Fig. 6 Striatal activity patterns are inconsistent with sampling-based codes.一个, Illustration of how the mean-matched Fano factor was computed115。The mean and variance (across trials) of the spike count for a single neuron contributed one data point to the scatter plot.Grey dots depict all neurons from an example session, time bin (here, centered 200 ms after odour onset), and odour (here, Variable 2).The grey line is the regression fit to all data, constrained to pass through zero and weighted according to the estimated s.e.m.of each variance measurement.Black dots are the data points preserved by mean matching at each time point, to eliminate the possibility that differences across time are driven by differences in firing rates, which could in principle violate the Poisson assumption.This transforms the distribution of mean counts from the grey to the black distribution.The regression slope for the mean matched data is plotted as the black line.Finally, the Poisson expectation of equal mean and variance is plotted in orange, with a slope of one.This procedure was performed independently on each session, time bin, and trial type.b, Time course of the computed mean-matched Fano factor (±95% c.i.) for the example session shown in一个。That is, the slope of black line in一个

is the height of the light blue, Variable 2 line inb

200 ms after CS onset.c, Quantification of mean matched Fano factor across second-long time periods. Consistent with cortical observations115, we see a quenching of variability upon CS onset (baseline:p = 0.002, 0.001, <0.001, <0.001 relative to odour, early trace, late trace, and outcome periods), and another one upon reward delivery (reward:p < 0.001, = 0.002, 0.006, 0.053 for baseline, odour, early, and late trace periods).d, Quantification of mean matched Fano factor across trial types, shown separately for each time period. In general, there is no tendency for Variable odours to elicit strong and sustained increases in variability, as would be predicted by sampling-based codes129(baseline, odour, early and late trace: allp’s > 0.05, except Nothing 1 vs. Variable 1 for odour:p = 0.032 uncorrected). However, reward delivery specifically drives yet another decrease in variability during the outcome period (Nothing 1:p = 0.570 for Nothing 2;p < 0.001 for Fixed odours;p = 0.002 for Variable odours).Extended Data Fig. 7 Additional detail for distributional model comparisons.一个, Schematic showing converged expectile code for each distribution (Nothing, Fixed, and Variable) learned by EDRL, as in Fig.2d。The activation of each value predictor is shown as a function ofÏ„, the level of pessimism or optimism. Together, they encompass the complete reward distribution.b, Same as一个, but for quantiles rather than expectiles.c, Same asb, but for a reflected quantile code in which pessimistic (D2, green) neurons correlate negatively withv我

(灰色的)。

Optimistic (D1, yellow) neurons are identical tov我, as in REDRL.d, Same as一个, but showing the converged value predictors for the Distributed Actor Uncertainty model123。In it, D1 and D2 MSNs learn exclusively from positive and negative RPEs, respectively, such that their difference at each level ofÏ„(grey dots) approximates each expectile, and their sum relates to the spread of the distribution. This drives maximal activity in response to Variable odours, which is why they separate out most clearly along PC 1.e, Same asd, but for a reduced version in which only a single pair of value predictors are learned with balanced positive and negative learning rates66((τ = 0.5).f, Same as一个, but for a categorical code in which distributions are encoded as a histogram33。Each neuron is imagined to correspond to a single reward bin, with its firing rate proportional to the height of that bin.g, Same asf, but for a Laplace code40。In the limit of infinitely steep reward sensitivities for the teaching signal, these value predictors converge to the probability that the reward delivered exceeds some threshold reward amount, the “exceedance probabilityâ€.This is simply 1 minus the CDF of the probability distribution in question.Neural activities are taken to be proportional to this 1 – CDF value.h, Same asg, but for a population of neurons that flips the encoding, and so is directly proportional to the CDF.i-k, Qualitative features of each code ina–hplus random noise. REDRL predictions are included in the box on the last line, for comparison.我, PCA projection for each code. Only quantile-like codes give rise to the pattern observed in the data.j, Hypothetical activity in response to each distribution, averaged separately over optimistic (blue) and pessimistic (purple) predictors for each code type. Only the reflected codes and AU model predict a noticeable uptick in Variable relative to Fixed odours.k, Percentage of simulated predictors that significantly correlate with mean reward either positively (blue) or negatively (purple) for each code type. Only the reflected and categorical codes have a substantial fraction of both types of cells. In practice the positive-coding predictors are optimistic and the negative-coding predictors are pessimistic.l, A hypothetical “distributional†code in which each neuron’s firing rate linearly correlates with either reward mean (左边) or variance (正确的)。m, Each trial type, replotted in mean–variance space. From this picture, it is clear that for this particular set of reward distributions, Fixed odours will be located at the midpoint between Nothing and Variable odours along PC 1, though altering the ratio of mean- to variance-coding neurons will move Fixed odours left or right along PC 1. Different sets of reward distributions could lead to different geometries.n, Mean z-scored firing rates for each neuron, in addition to being higher for rewarded than unrewarded odours (p < 0.001), were also higher for Variable than for Fixed odours (p = 0.006), as assessed by an LME with neuron level observations, averaged over trials, and session-level random effects nested within mouse.o, Same as Extended Data Fig.2o, but for mean. Fraction is higher than chance for both positive- and negative-coding cells (bothp’s < 0.001).Extended Data Fig. 8 REDRL consistently predicts population responses across three additional classical conditioning tasks.一个, Reward distributions for the Bernoulli (顶部), Diverse Distributions (中间), and Fourth Moments (底部)任务。b, Anticipatory lick rate during the late trace period for each task and trial type. (Bernoulli task: 0%,p < 0.001 versus 50, 80, and 100%; 20%,p < 0.001 versus 80 and 100%;50%,p < 0.001 versus 100%; 80%,p = 0.008 versus 100%. Diverse Distributions task: CS 1,

p

= 0.008 versus CS 2,p < 0.001 versus CS 3–6; CS 2,p < 0.001 versus CS 3–6; CS 3,p = 0.560, 0.243, <0.001 versus CS 4–6, respectively; CS 4,p = 0.560, 0.001 versus CS 5–6, respectively; CS 5,p = 0.009 versus CS 6. Fourth Moments task: Nothing 1 or Nothing 2,p < 0.001 versus Uniform 1, Uniform 2, Bimodal 1, and Bimodal 2; Uniform 1,p = 0.570, 0.336, <0.001 versus Uniform 2, Bimodal 1, and Bimodal 2, respectively; Uniform 2,p = 0.126, <0.001 versus Bimodal 1 and Bimodal 2, respectively; Bimodal 1,p = 0.016 versus Bimodal 2). Dashed line indicates mean reward for that trial, given on the secondaryy-轴。c, 2D PC projections for example sessions in each task.d, 2D PC projections for each model on each of the three tasks.e, Quantification of Pearson correlation between the Euclidean distance matrices measured between each trial type along either PC 1 (左边) or PC 2 (正确的)。(Bernoulli task: PC 1 relative to REDRL,p = 0.994, 0.459, 0.284, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, 0.861, 0.888, 0.772, <0.001 for Expectile, Quantile, Reflected Quantile, Distributed AU, Partial Distributed AU, AU, Categorical, Laplace, Cumulative, and Moments codes, respectively; PC 2 relative to REDRL,p = 0.666, 0.964, 0.653, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, 0.078, 0.002, <0.001. Diverse Distributions task: PC 1 relative to REDRL,p = 0.999, 0.963, 0.985, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, <0.001, 0.993, 0.994, 0.011; PC 2 relative to REDRL,p = 0.863, 0.077, 0.050, 0.096, 0.054, 0.147, 0.428, 0.038, 0.065, 0.047. Fourth Moments task: PC 1 relative to REDRL,p = 0.891, 0.990, 0.997, 0.951, 0.928, 0.978, 0.828, 0.984, 0.927, 0.921; PC 2 relative to REDRL,p < 0.001, 0.127, 0.325, 0.167, 0.305, 0.891, 0.839, 0.075, 0.060, 0.021).f, Difference between observed and trial-type shuffled data in the percentage of cells significantly correlating positively or negatively during the late trace period with either mean (左边) or residual variance (正确的)。In the Bernoulli task, mean and variance are orthogonal by design, so residual variance is equivalent to variance.In the Fourth Moments task, mean and variance are fully colinear, so residual variance is always equal to zero.(Bernoulli task:p < 0.001, = 0.013, 0.112, 0.225 for Positive and Negative mean and residual variance differences relative to zero, respectively. Diverse Distributions task:p < 0.001, = 0.009, 0.312, 0.026. Fourth Moments task: both meanp’s < 0.001).g, Pseudo-population parallelism score across subregions in the Fourth Moments task, comparing neural representations of Uniform and Bimodal distributions (relative to chance level of 0:p = 0.291, 0.150, 0.851, 0.002, 0.465, 0.832, 0.775, 0.175, 0.548 for OT, VP, lAcbSh, core, VMS, VLS, DMS, DLS, and All Subregions, respectively. Same order applies to remaining panels in this figure). Pseudo-populations were constructed as in Extended Data Fig.2l, and mAcbSh was excluded because of too few neurons in all animals.h, Same asg, but for CCGP (relative to chance level of 0.5:p = 0.975, 0.997, 0.948, 0.150, 0.852, 0.945, 0.474, 0.693, 0.337).我, Same asg, but for pairwise decoding (Across- vs. Within-distribution:p = 0.893, 0.411, 0.012, 0.184, 0.590, 0.762, 0.256, 0.327, 0.311).j, Same asg, but for congruency analysis (Congruent vs. Incongruent 1:p = 0.457, 0.411, 0.333, 0.606, 0.833, 0.966, 0.956, 0.106, 0.225; Congruent vs. Incongruent 2:p = 0.993, 0.014, 0.265, 0.228, 0.602, 0.978, 0.073, 0.760, 0.007).Extended Data Fig. 9 Additional data for 6-OHDA experiments.一个, Consensus heat map74of all five animals’ lesion locations. 6-OHDA was injected in the lAcbSh but diffused into the VLS, so we considered both regions to be lesioned. We excluded OT, despite the fact that it was often lesioned, because it is not physically contiguous and showed weaker evidence of distributional coding in control animals. The illustration was adapted from ref.74, Elsevier.b, Behavioral decoding analysis comparing fully intact animals (n = 3) and unilaterally lesioned (n = 9) animals across time. For this analysis, animals were considered lesioned if they had received any 6-OHDA injection, even if that hemisphere was never recorded or was mistargeted relative to Neuropixels recording location.c, Quantification of behavioral classifier accuracy during the late trace period. While across-mean behavioral decoding was stronger in the control than the lesioned animals (effect of lesion:p = 0.006, 0.001, 0.173 for Nothing vs. Fixed, Nothing vs. Variable, and Fixed vs. Variable, respectively), both groups of animals clearly learned the task and had above-chance across-mean decoding (p < 0.001 compared to chance level of 50% for both Nothing vs. Fixed and Nothing vs. Variable in control as well as lesioned animals). Interestingly, Fixed vs. Variable classification was also weakly significant (p = 0.032 relative to chance level of 50%) for fully intact control animals, providing behavioral evidence that they did in fact learn this distinction.d, Median fraction deviance explained by the GLM (Extended Data Fig.5) for neurons in control vs. lesioned hemispheres (p = 0.831).

e

, Difference in fraction deviance explained between full model and models in which history (左边;p = 0.474), reward (第二;p = 0.623) sensory/reward prediction (第三;p = 0.861) or motor (正确的;p = 0.618) regressors had been dropped out.f, Absolute kernel strength of history (左边;p = 0.634), reward (第二;p = 0.089), expectiles (第三;p = 0.448) or motor (正确的;p = 0.145) regressors.Extended Data Fig. 10 Additional data for two-photon calcium imaging experiments.一个, D1 MSN activity.顶部, heatmaps showing average z-scored deconvolved calcium activity in response to each odour for each neuron, as in Extended Data Fig.2b。底部, grand average z-scored deconvolved calcium activity across all neurons.b, Same as一个, but for D2 MSN activity.c, Anticipatory lick rates for each trial type, computed during the late trace period separately forDrd1-cre和Adora2a-creanimals (in which we imaged D1 or D2 MSNs, respectively).(Drd1-cre, Nothing 1 or Nothing 2:p < 0.001 versus Fixed 1, Fixed 2, Variable 1, and Variable 2;Drd1-cre, Fixed 1:p = 0.960, 0.458, 0.642 versus Fixed 2, Variable 1, and Variable 2, respectively;n = 4 mice, 29 sessions.Adora2a-cre, Nothing 1 or Nothing 2:p < 0.001 versus Fixed 1, Fixed 2, Variable 1, and Variable 2;Adora2a-cre

, Fixed 1:p

= 0.790, 0.608, 0.686 versus Fixed 2, Variable 1, and Variable 2, respectively;n = 4 mice, 41 sessions. Main effect of genotype, relative to Nothing 1:p = 0.785; interaction of genotype and trial type:p = 0.888, 0.387, 0.525, 0.350, 0.331 for Nothing 2, Fixed 1, Fixed 2, Variable 1, and Variable 2, respectively;n = 8 mice, 70 sessions).如图1C, dashed lines indicate mean reward for that trial type.d, Fraction of neurons whose late trace activity increased (顶部) or decreased (底部) relative to baseline, shown separately for D1 (左边) and D2 (正确的) MSNs and unrewarded (Nothing) versus rewarded (Fixed and Variable) odours (x-轴);these trial types were pooled before analysis.As expected, a larger fraction of D1 MSNs increases to rewarded rather than unrewarded odours (p = 0.006; mean ± s.e.m. = 0.524 ± 0.074), while there is no difference in the fractions that decrease (p = 0.423; mean ± s.e.m. = –0.098 ± 0.106). Meanwhile, for D2 MSNs, a significantly greater fraction of neurons change their activity on rewarded compared to unrewarded trials, by either increasing (p = 0.022; mean ± s.e.m. = 0.189 ± 0.043) or decreasing (p = 0.016; mean ± s.e.m. = 0.133 ± 0.027) their activity relative to baseline. Asterisks andp-values report the results of paired samples Student’st-tests on rewarded vs. unrewarded fractions across mice.e, REDRL predicts higher variance across trial types for optimistic than for pessimistic reward predictors on average (左边), which is also true in the two-photon data for D1 and D2 MSNs, respectively (正确的)。Small dots are averages within sessions, medium dots are averages within mice, and large dots with error bars show averages ± 95% c.i.across mice (p = 0.017 for effect of genotype).Extended Data Fig. 11 Additional detail for distributional model manipulations.一个, Schematic showing how optogenetic perturbations were simulated for an expectile code (from EDRL). Optimistic (blue) or pessimistic (purple) predictors were shifted from their original values (semi-transparent grey circles) and clamped to low or high values to mimic inhibition (左边, “xâ€s) or excitation (正确的, triangles), respectively. Panels on the right depict the ground-truth reward distribution, its mean (black line), and the means of the manipulated sets of value predictors (blue or purple dashed lines).b, Same as一个, but for a quantile rather than expectile code.c, Same asb, but for a reflected quantile code. The additional, leftmost panel for each distribution depicts the activity of D1 (yellow) and D2 (green) MSNs at baseline (semi-transparent circles) and after manipulations (opaque “xâ€s and triangles). These are what are directly clamped by the simulated optogenetic inhibition or excitation. As a result, the effect on the implied value predictors (middle panel) corresponding to D2 MSNs are of opposite sign, as is the change in predicted mean (right panel).d, Same asc, but for the Distributed Actor Uncertainty (AU) model. Since D1 and D2 MSN activities in this model can exceed the maximum reward value, the left panel shows that perturbations were simulated by adding or subtracting a fixed amount from each activity level (opaque “xâ€s and triangles) relative to baseline (semi-transparent circles). The middle panel plots the resulting value predictors, computed as the pointwise differences between D1 and D2 MSN activities, for pessimistic (purple) and optimistic (blue) manipulations in comparison to baseline (grey semi-transparent circles).e, Same asd, except that only the optimistic or pessimistic half of MSNs were manipulated to simulate perturbations of D1 or D2 MSNs, respectively.f, Same asd, except for the original Actor Uncertainty (AU) model in which there is only one pair of value predictors with balanced learning rates (τ = 0.5).g, Schematic showing how optogenetic perturbations were simulated for a categorical code (from CDRL), which effectively represents the reward distribution using a histogram. Pessimistic (0, 2 μL; purple) or optimistic (6, 8 μL; blue) bins were clamped to 0 or 1 to simulate inhibition or excitation, respectively, relative to baseline (grey). The resulting distributions were normalized to sum to one (see 方法)。Dashed vertical lines show the means of the ground-truth (black) and manipulated distributions.h, Same asg

, except for a Laplace code

40in which each neuron corresponds to the height of 1 – CDF at a particular point. While the baseline case is always monotonically decreasing, simulated excitation or inhibition can change this. Means were computed by differentiating and then normalizing (see 方法)。我, Same ash, except for a cumulative code where each neuron corresponds to the height of the CDF at a particular point.j, Actual differences in lick rate during the last half second of the trace period in response to inhibition of D1 or D2 MSNs, copied from Fig.5f。k, Same asj, but for excitation.l, Predicted difference in mean reward due to inhibition for REDRL and each of the alternative models in一个我。m, Same asl, but for excitation.n, Average lick rates in each group of animals, with (blue and purple) or without (black) manipulations, rarely exceeded 5 Hz.补充信息Supplementary DiscussionThree extensions to the discussion in the main text of the paper, on (1) distinguishing expectile- and quantile-based versions of distributional RL; (2) contrasting our results with non-RPE-based accounts of dopamine; and (3) considering probabilistic coding in the brain more broadly.补充表1Full specification of all linear mixed effects models (LMEs).权利和权限Springer Nature或其许可人(例如,社会或其他合作伙伴)根据与作者或其他权利归属人的出版协议享有本文的独家权利;本文接受的手稿版本的作者自我构造仅受此类出版协议和适用法律的条款的约束。重印和权限关于这篇文章引用本文Lowet, A.S., Zheng, Q., Meng, M.等。用于分配加固学习的对手纹状体电路。自然(2025)。https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08488-5下载引用已收到:2024年1月2日公认:2024年12月4日出版:2025年2月19日doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08488-5, Predicted difference in mean reward due to inhibition for REDRL and each of the alternative models in a–i. m, Same as l, but for excitation. n, Average lick rates in each group of animals, with (blue and purple) or without (black) manipulations, rarely exceeded 5 Hz.

Supplementary information

Supplementary Discussion

Three extensions to the discussion in the main text of the paper, on (1) distinguishing expectile- and quantile-based versions of distributional RL; (2) contrasting our results with non-RPE-based accounts of dopamine; and (3) considering probabilistic coding in the brain more broadly.

Supplementary Table 1

Full specification of all linear mixed effects models (LMEs).

Rights and permissions

Springer Nature or its licensor (e.g. a society or other partner) holds exclusive rights to this article under a publishing agreement with the author(s) or other rightsholder(s); author self-archiving of the accepted manuscript version of this article is solely governed by the terms of such publishing agreement and applicable law.

About this article

Cite this article

Lowet, A.S., Zheng, Q., Meng, M. et al. An opponent striatal circuit for distributional reinforcement learning. Nature (2025). https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08488-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41586-024-08488-5