AI recreates the faces of enslaved people in Brazil based on descriptions by an abolitionist

作者:Joan Royo Gual

On the arduous path of historical reparation for the millions of Africans who were enslaved in Brazil over nearly four centuries, there are small gestures filled with symbolism. One is to recover the identity of those who never had the right to exist as human beings.

This is the aim of an exhibition that just opened at the Public Archives of the State of São Paulo, in the city of the same name. Using the detailed descriptions that lawyer and abolitionist Luiz Gama made of dozens of enslaved people, their faces have been recreated using Artificial Intelligence (AI). The idea came from one of the archive’s staff, the artist Diego Rimaos, who wanted to pay tribute both to these anonymous individuals and to the work of Gama, one of the heroes of the Black Brazilian struggle for freedom.

The exhibition is titled I, the scribe who wrote… because it focuses on the period when Gama worked as a clerk in a police station. He dedicated his time to exploiting legal loopholes to free as many people as possible from slavery. The documents that formed the basis of the exhibition date from 1862 to 1866, a period in which, in theory, enslaved Africans could no longer enter the country. Only in theory: Years earlier, in 1831, a law had been passed to prohibit the slave trade and thus satisfy abolitionist pressure from the United Kingdom, Brazil’s main ally at the time. Brazilians knew this law would not catch on, and they jokingly dubbed it lei para inglês ver (law for the English to see). The expression is still used today to refer to legal norms that are not enforced in practice.

Theoretically, no more slaves could arrive in Brazil anymore, although the reality was very different: “A lot of people turned a blind eye. Gama, as an abolitionist, took advantage of his status as a public official to conduct these searches at a police station and get these people out of a situation that, on paper, was irregular,” says the artist and archivist Rimaos over the phone.

Under Brazilian law, the subjects of this exhibition should never have been enslaved in the first place: “Their status was that of a free African, which was different from that of a freed slave.” For practical purposes, the emancipation documents they were granted through Gama’s intervention allowed them to live as something akin to immigrants with residency permits, but always under someone’s guardianship and with various restrictions. Even free, they were far from being full citizens.

Photography already existed at the time, but it was very expensive and reserved for the elites, hence the importance of the abolitionist lawyer’s descriptions, because that would be the document they would carry with them to identify themselves: “Olegário, from the Benguela nation, free African, round face, small eyes, regular lips, flat nose, regular and pierced ears, mark in the middle of the chest, the time at which he was imported is unknown...”

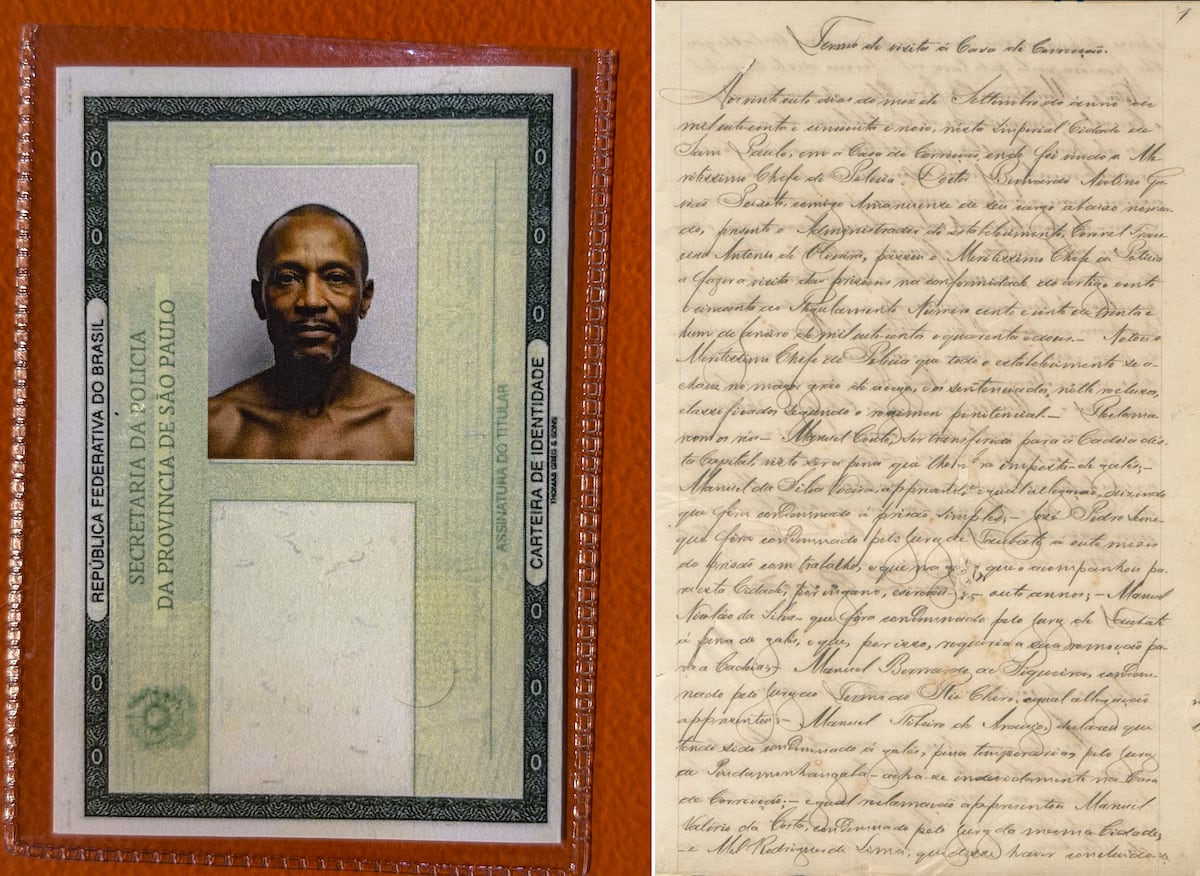

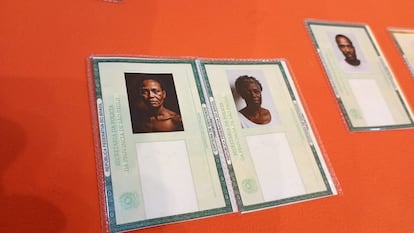

Rimaos took these texts and ran them through AI tools to generate their faces, although he had to make several corrections because the technology was giving them hair and hairstyles more typical of the 21st century. It’s the work of an anachronistic algorithm, says the artist. The new faces, in the classic passport photo format, now appear on contemporary identity documents, like the ones all Brazilians carry in their wallets.

The exhibition also serves to highlight the legacy of Luiz Gama, who had a fascinating life. He was born free in the city of Salvador de Bahia, the son of a freed slave (most likely Luisa Mahín, who participated in various anti-slavery revolts) and a Portuguese man. At the age of 10, his father, drowning in debt, sold him as a commodity. As a young man, Gama learned to read and write in the house where he worked as a slave, and soon afterward, he fought a legal battle to prove his right to be a free man.

He studied law independently, and although he was prevented from enrolling, he was allowed to audit classes at the elite São Paulo Law School. Later, as a rábula (a lawyer who could act in court despite lacking a formal degree), he fought for the freedom of hundreds of enslaved people. His manuscripts, kept in the São Paulo archives, were recognized in January of this year by UNESCO as part of its Memory of the World program.

Sign up for our weekly newsletter to get more English-language news coverage from EL PAÍS USA Edition