Will the Real AI Please Stand Up?: Artificial Intelligence vs. Authentic Insight

作者:Austin Kocher

Last week, I gave a talk at the Newhouse Impact Summit on the role of artificial intelligence in public scholarship and research communication. The talk wasn't intended to be an explanation of the advantages and disadvantages of AI, but rather an exploration of deeper question about what's left for human expertise in an AI-driven world. I find it more important than ever to question how we conceptualize human expertise and authenticity when machines can generate increasingly sophisticated content.

In my view, one of the most significant opportunities that AI presents is that it prompts us to think seriously about the value of human intelligence. AI gives us something of a framework for focusing our limited efforts on things that are original, valuable, and uniquely human, as opposed to things that can be easily automated or automatically generated.

I believe it was the technoskepticist Cal Newport who once said that there are things that humans should never try to get good at—like email—because getting good at email does nothing for society (other than perhaps please your boss). Instead, we should focus on cultivating what Newport calls “deep work”, work that uses the unique advantages of deep human thought and creativity to come up with something new. The flip side of that coin is that AI is making it harder for average ideas to hide behind average systems, because AI is so efficient precisely at producing average ideas.

This is my first talk and essay specifically on the topic of AI, so please consider these remarks to be very preliminary. For that reason, I would greatly appreciate any feedback, questions, comments, and disagreements you may have with the tentative observations in this post. I would really like to learn from those of you who have thought about this more than I have or have expertise in this area.

Finally, I want to express my profound thanks for Gina Luttrell, Margaret Talev, Kris Northrop, and all of my other colleagues at Syracuse University and beyond who made the entire day a success. I learned a lot and I met some terrific new scholars, such as Matthew Salzano, who generously sent me some great references on the rhetoric of expertise. While I’m focusing on my own talk in this post, the other talks throughout the day were excellent, probably more sophisticated than my ramblings. If you’re in the D.C. area, stay tuned to events at the Institute for Democracy, Journalism and Citizenship.

In order to try to capture the essential tension that I’m trying to interrogate, I'm playing on the acronym AI in the title to signal both artificial intelligence and authentic insight. When I say AI, I am generally referring to consumer-facing generative AI, such as ChatGPT, Claude, and Gemini. I am aware that my own knowledge of the full range of AI is limited, but this is what I know for now.

Coming at this from the perspective of a researcher who spends considerable time writing for the public and talking to reporters and policymakers, I've been thinking through how AI changes public communication, including for academics. How does it open up opportunities for academics to do a better job of communicating publicly? And where might AI still lack—not so much raw capabilities, but where does AI fall short when it comes to meaningful public communication?

When it comes to communicating complex topics to the public, it's rarely as simple as just getting the right answer or providing an explanation. If it were that simple, you could ask why reporters and journalists would even reach out to academics or experts for interviews or quotes.

These questions gets at an underlying point: expertise and knowledge aren't only the result of combinations and permutations of bits of knowledge, facts, and details. Human expertise is tied to personality, social networks, and media presence. People want someone to either follow, blame, or support. There's something about how people think better or are more committed to their ideas when those ideas are attached to a personality with their own flavor, idiosyncrasies, original ideas, as well as their own mistakes and blind-spots.

These dynamics becomes particularly interesting when we consider that artificial intelligence is taking off at the same time that we have the rise of influencers. The role of academics, public scholars, and domain experts might be understood as occupying a social space somewhere between these two extremes, or between these two forms of popularized knowledge of questionable quality and value.

So on one side, we have artificial intelligence, which is extremely informative and sophisticated but depersonalizes knowledge and information. On the other side, we have influencers who aren't content area or domain experts but who hyper-personalize knowledge by building followings and attaching certain practices and perspectives to themselves as personalities. Influencers don't necessarily conform to strict quality controls or possess deep subject matter expertise.

Public scholars and experts might serve as a crucial middle ground by combining the rigor and depth of specialized knowledge that influencers lack with the authentic human voice and accountability that pure AI lacks. Hence the idea of “authentic insight”, or knowledge that is original, valuable, and rigorously-produced, but reflects a distinctly human form of authenticity and voice.

In my work studying the immigration enforcement system, I've identified three specific areas where AI currently falls short in some way, not necessarily because of a lack of computing power but because of the ways in which knowledge about immigration is embedded in social and political relations in the real world.

First, the data I work with is highly specialized administrative data that doesn't usually require super complicated statistics but does require data science tools, large databases, and constant research. This data requires a high level of technical, institutional, and historical knowledge, as well as qualitative insights and inferential judgment that I haven't yet seen AI perform effectively. This is the kind of contextual “real world” reasoning that I don’t think AI does particularly well. Or even when AI attempts this type of reasoning, the number of people who are capable of validating those outputs are limited.

Second, studying immigration enforcement and then communicating about it occurs in a highly polarized communication space. This necessarily means not just communicating facts, but putting those facts in context. All of that requires judgment. As I said above, it's not just about getting the numbers right, but narrating them in a spontaneous and authentic way that can be held accountable, either lifted up as a credible source or criticized and fact-checked.

Third, my research focuses on what we call closed institutions. AI is built around information, data, and text that's available for learning, but the data and information from government agencies that do immigration enforcement is only selectively released to the public, not in great bulk and not with much explanation. Secrecy is a fundamental component of how these agencies operate, so there isn't a lot of information in the public domain about the precise operational and data-driven questions I'm asking.

None of this undermines the incredible resource that AI has been for me when doing desk research, clarifying points of historical fact (with checked citations!), and thinking through various ways to narrate new policy developments. But I have not found AI to represent any significant threat to the work I am doing now.

These observations led me in my talk to identify three areas that need rethinking in the age of AI.

Rethinking Expertise

I prefer to use the term "expertise" rather than "experts," mostly because "experts" gives the idea that a person simply is this rather than having an ongoing area of knowledge that must be maintained and is domain-specific. I would describe myself as having expertise in certain areas of U.S. immigration policy and data, but I wouldn't refer to myself as an expert full stop. Just because I know a lot about one thing doesn't mean I possess that level of understanding in all domains—even within immigration, there are many areas I don't know well.

Real knowledge and experience about specific domains of politically sensitive topics like immigration enforcement still does something that AI cannot do. As much as AI depersonalizes and influencers hyper-personalize (but not always reliably), there's still an important place for nonpartisan expertise in the public realm.

AI isn't necessarily replacing human expertise, but it is interrogating it, sometimes augmenting it, and really asking us to think about what humans can uniquely contribute and say, and in what contexts, in ways that aren't easily replaceable.

Rethinking Pedagogy

For education, this definitely comes down to making sure students are exposed to questions and projects that are not simply AI-reproducible. I'm talking about projects with original components that aren't just about instructing students not to use AI, but asking them to do things that are impossible to do with AI alone.

For example, a recent project might involve going into archives, looking at historical documents, making sense of them, and creating a dataset and working database from what they found. Even in that work, AI can be quite useful in helping to fill in context that students don't have. AI can act as a tutor along the way. But ultimately, projects like this offer students a chance to do work they can feel confident can't just be done by a computer. It's also a form of accountability that shows which students are ready to do original work.

Rethinking Partnerships

In immigration research and communication, I think a lot about how authenticity is socially constructed through networks, media, and public communication. Authenticity isn't something you can come up with on your own. Authenticity is rooted in the networks you have, the audiences you have, and the relationships you build.

It's important not only to capitalize on those relationships and networks to help hold us accountable and give us opportunities to do authentic human work, but also to speak back to the technology fields about this concept of authenticity and how to enable rather than erase it.

Whether it's artificial intelligence or human intelligence, for anyone to care, learn, read, or listen, there have to be distribution networks. We need to understand how different platforms manage communication, how to take advantage of opportunities, and possibly how to shape how some platforms distribute knowledge.

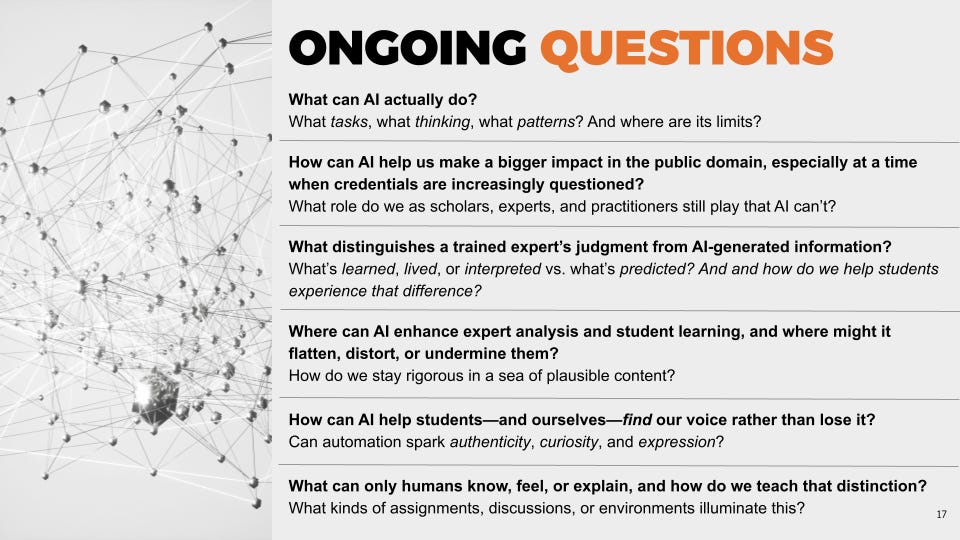

There are several ongoing questions in my work about how we can use AI to help academics have a bigger impact in the public domain, especially when formal credentials are increasingly questioned by the public. What distinguishes a trained expert's judgment from AI-generated information? Where can AI enhance expert analysis and student learning, and where might it flatten, distort, or undermine these things?

I think academics can use AI to help communicate complex findings to the public. AI can be helpful in thinking through a paper, an academic talk, or an op-ed. There are ways that AI can iterate on research questions faster than humans. But the risk is that over-reliance on AI leads back to a very neutral, ChatGPT-sounding voice and set of questions. It becomes obvious when AI is driving the entire project because it loses that sense of creativity and originality that typically comes from a person having interesting, quirky, bizarre, crazy ideas.

In a way, AI raises the stakes. Academia has its own norms and trends toward a median tone, and academia is conformist in its own way. The more that AI can reproduce average, middle-of-the-road research, the more it offers incentives for scholars to have more interesting questions and more distinctive approaches than what AI can generate.

As I've reflected on my own experience working with journalists and thinking about public scholarship, I believe that scholarship thrives on openness and reproducibility. Public scholars in particular can put methods out there, put findings out there, and learn from how people react and what feedback they get.

One of the things I love most about being able to put research out there through different channels is that I get tremendous feedback on what I'm doing, which means I tend to learn very quickly if I've made a mistake or if people find something interesting or how folks are using my work. There's enormous potential to continue staying flexible and open while ensuring that our research is communicated to broad audiences and that we're working with people to spread good ideas and information.

To close this out, I think that the rise of AI doesn't diminish the need for human expertise—it instead clarifies what makes human expertise valuable and pushes us to be more intentional about cultivating and sharing authentic insight in a world increasingly filled with artificial intelligence.

Since this was a talk with more questions than answers, I’ll include my final slide here as food for thought. Please share your questions and answers in the comments below.

Just a reminder that this newsletter is only possible because of your support. If you believe in keeping this work free and open to the public, consider becoming a paid subscriber. You can read more about the mission and focus of this newsletter and learn why, after three years, I finally decided to offer a paid option. If you already support this newsletter financially, thank you.