Twenty restaurants with the same Poughkeepsie address. A Newburgh eatery selling a Mr. Beast burger. A seemingly locally owned diner that is actually a Denny’s.

These are some of the legal yet confusing ways restaurants are taking advantage of third-party food apps, five years after the pandemic turned delivery into a lifeline for hungry diners and cash-strapped eateries. But long after social distancing measures have been lifted, these apps have only cemented their presence, while ghost kitchens — which have no brick-and-mortar space and exist solely online to fulfill delivery orders — have surged across the country.

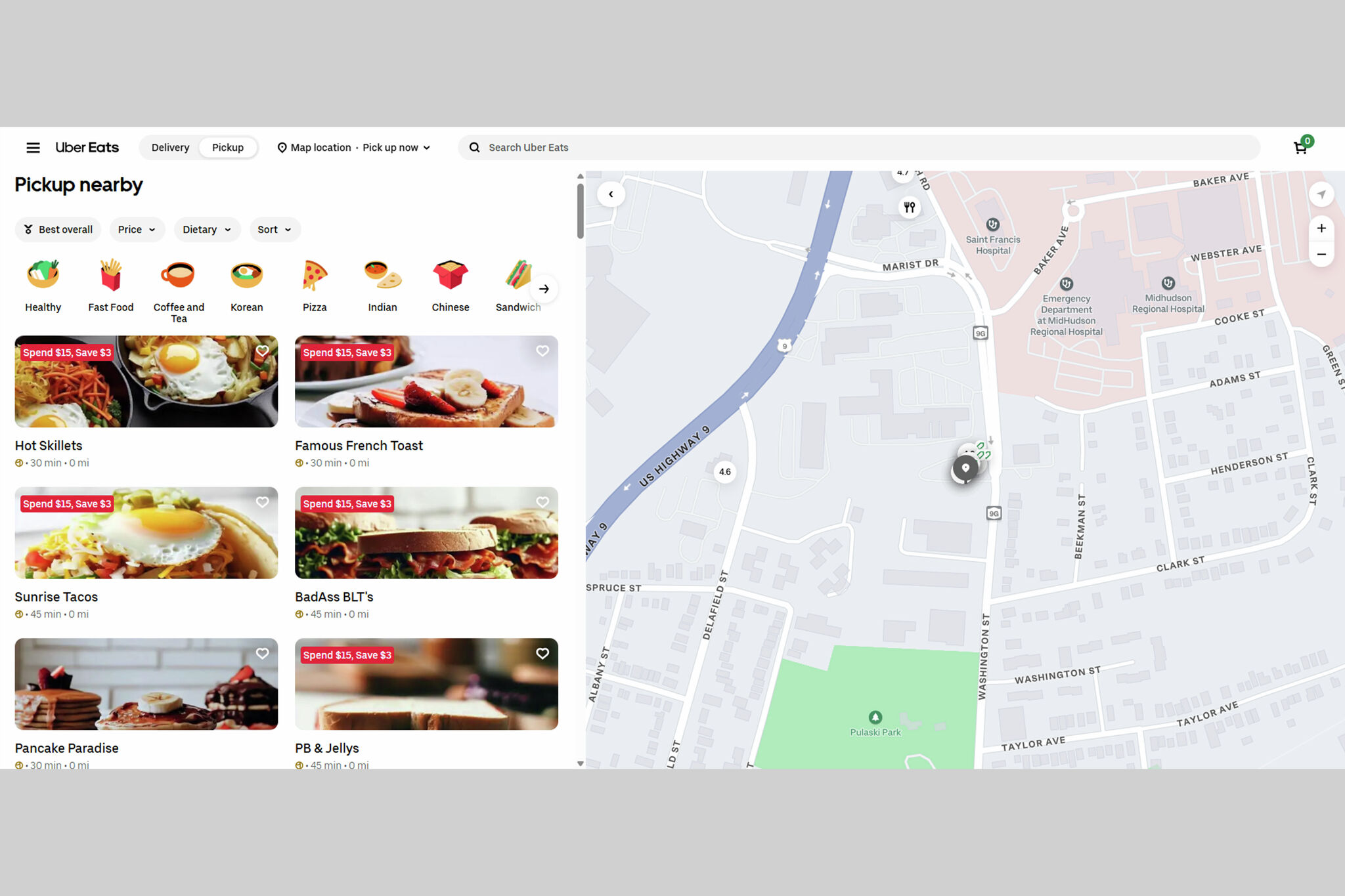

The Hudson Valley dining scene isn’t different. Scrolling apps like Uber Eats and DoorDash gives the illusion of variety. But further investigation reveals a complex landscape, where it’s typical to find multiple virtual brands based in one location, chain restaurants fronting as mom-and-pop eateries, AI-generated images of food, and actual local restaurants, all elbowing their way to the top of the app.

Article continues below this ad

Generic names, AI-generated images

A typical search of an online ordering and delivery platform yields many listings. Fast food restaurants are to be expected. Then, there are the well-known local staples you may have visited before. Finally, there are eateries with names that fall into the uncanny valley. They sound like big chains, but you can’t remember driving by them. That’s because they don’t exist in the physical realm but in the universe of food delivery apps.

A Times Union reporter found several Hudson Valley listings that met those characteristics, many with clickbait names and AI-generated photos, including “Grandma’s Pasta Company,” “Sunrise Tacos,” “Hot Skillets,” “Anytime Breakfast Sandwiches,” and “Famous French Toast.” On one app, there were 20 that all traced back to the same Poughkeepsie restaurant, Palace Diner on Washington Street.

When the reporter called the diner, its owner, George Papas, said these were actually virtual brands. Though he couldn’t remember when, he said a company called Profit Cookers had reached out offering the restaurant the brands, which are only available for delivery and operate out of kitchens in existing restaurants.

Article continues below this ad

Palace Diner is far from the only restaurant to diversify its branding on food delivery apps as a way to boost sales. And these same virtual brands don’t just exist in Dutchess County. Besides a roadside diner in Fishkill, listings for spots like “Grandma’s Pasta Company” were also found in Ossining, New Rochelle and Queens, and in Connecticut, New Jersey, Pennsylvania, Maryland, North Carolina, Georgia, Florida and Arizona.

The number for one of those was linked directly to Profit Cookers. Its CEO, Kirk Mauriello, explained these weren’t different restaurants operating out of a single location, but virtual brands that provide their own menu and recipes to restaurants that license them. The company handles marketing and orders and pays the restaurant by the end of the week. The restaurant simply has to cook the food and hand it to a delivery driver.

Mauriello founded Profit Cookers in 2020 and has since expanded to 29 states and 300 restaurant “partners” that license its 30 virtual brands, each specializing in a dish or type of food, like mac and cheese or tacos. In New York state, 25 restaurants work with Profit Cookers, Mauriello said.

“We license only to locally owned restaurants around the country because we wanted to have good quality control,” he said. “We are helping the communities and helping those local businesses create a new business model within the restaurant business.”

Article continues below this ad

Mauriello said on average, restaurants that license Profit Cookers’ virtual brands make $250,000 more per year from those brands. For every $100 that comes from one of the virtual brands, 60% goes to the restaurant, the food delivery app gets about 30% and Profit Cookers takes the remaining 10%.

For the local restaurants interviewed by the Times Union, these virtual brands weren’t the main drivers of revenue. Papas, the Palace Diner owner, said they account for less than 1% of his sales, but “every little bit helps.”

Several virtual brands like “Sunrise Tacos” and “Eggy’s Omelettes” operate out of Palace Diner in Poughkeepsie.

Maria M. Silva/Times UnionPete Papageorgantis, the owner of Anna’s Restaurant in Newburgh, was approached by a sales representative for a virtual brand company offering him a license for their “Breakfast Beauties” brand, which sells breakfast sandwiches. At first, Papageorgantis was skeptical — his restaurant has been open since the 1980s and was able to stay afloat without food delivery apps. But he thought they had to “keep up with the times,” so he accepted the “Breakfast Beauties” license. The virtual brand brings one or two weekly orders, so Papageorgantis said he is considering discontinuing it.

Article continues below this ad

Restaurant operators like Papageorgantis are used to volatility in an industry that typically sees a 3% to 5% profit margin. While restaurants are generally performing better than last year, the industry continues to grapple with rising food, utility and labor costs, as well as declining patronage as Americans cut back on dining out, according to the 2025 James Beard Foundation industry report.

Having an online presence can lead to a 5% revenue increase, so many restaurants have jumped at the opportunity. In 2024, the online food ordering industry was valued at an estimated $353 billion and it is projected to reach $500 billion by 2029, according to CloudKitchens, a Los Angeles-based company that operates ghost kitchens and develops related technology.

“People found out how useful (the apps) were, and they didn’t have to leave their house, especially for families who have kids and have to go to a restaurant and sit down,” said Janet Irizarry, a former restaurant owner who created HudsonValleyEATS.com and teaches hospitality as an adjunct professor at the Culinary Institute of America. “The other thing is, (the apps) weren’t good before, but they’ve gotten better because so many people are using them … and restaurants also realized that using DoorDash or Uber Eats is a form of marketing.”

Who am I really ordering food from?

Despite the growth potential, some experts (and consumers on many Reddit threads) say these online-only brands pose transparency issues and food handling questions.

Article continues below this ad

In early 2020, online orderers were surprised to learn that behind the seemingly local Pasquales Pizza was a Chuck E. Cheese. Other restaurants have since jumped on the virtual brand bandwagon, including Denny’s, which has three virtual brands via a partnership with DoorDash — The Meltdown, The Burger Den and Banda Burrito — and Chili’s, with It’s Just Wings. These operate out of these restaurants’ existing kitchens, including in the Hudson Valley. Diners can order from the Meltdown inside Denny’s locations in Newburgh and Middletown.

“We have been transparent about Denny’s operating these brands since their inception almost five years ago,” said a Denny’s spokesperson when a reporter inquired about customers potentially being confused. “These brands give us the flexibility to meet guests where they are, particularly younger audiences who are more likely to discover and engage with restaurants through third-party delivery apps. The menus are designed to complement our classic Denny’s offerings while also reaching new fans who may be craving a burger, melt or burrito delivered right to their door. We advertise these brands exclusively via the delivery apps — allowing us to serve guests looking for variety.”

Questions from consumers have led food delivery apps to become more stringent on what they allow on their sites. On DoorDash, virtual restaurants are labeled as such. Two years ago, Uber Eats began cracking down on restaurants that duplicate menus under different names.

Restaurants and virtual brands using Grubhub have several requirements: they must “sufficiently differentiate themselves” from their parent brand, carry distinct menus so that they don’t crowd out other restaurants with duplicative offerings, and consistently meet high service standards.

Article continues below this ad

“If they fall short of these guidelines, they may be removed from the platform,” a Grubhub spokesperson said.

“We uphold high-quality standards on our platform, which include prohibiting the use of AI-generated menu photos,” a DoorDash spokesperson said. “As part of our regular content reviews, we work closely with partners — including Profit Cookers — to ensure all menu images accurately reflect the dishes customers will receive. When we identify images that don’t meet these standards, we promptly remove them, and where possible, replace them with genuine, representative photos.”

But Mauriello, from Profit Cookers, said the company uses AI-generated imagery because the technology has improved so much “that we can pinpoint it down to exactly what our food looks like.” If a restaurant partner had a health violation, Mauriello said the company would have to remove its brand from the business.

“The whole imagery isn’t the same as the experience, but people don’t want to look at food in a box online,” Mauriello said.

Article continues below this ad

A spokesperson from the state Department of Health said its rules when it comes to handling, preparation and storage apply to all food service operators, regardless of whether the establishment has a dining space or functions solely as takeout or delivery.

Tasting the menu

All the reporting made a Times Union reporter hungry. While scrolling DoorDash, she found a couple of restaurants that sparked her interest: Eggy’s Omelettes and Mac Mac Cheese.

The reporter ordered an assortment of random items — a Greek omelette ($15.99), a loaded bacon mac and cheese ($14.99) and a side of potato salad ($8.99) — and headed off to the location with the pickup instructions in mind: “This is a virtual brand — go inside Palace Diner to pick up order.”

Article continues below this ad

A Times Union reporter recently placed an order for loaded bacon mac and cheese, a Greek omelette and a side of potato salad from one virtual brand.

Maria M. Silva/Times UnionForty-five minutes later, the reporter picked up the food from the Palace Diner, which was still serving a few tables during late lunch. There was no mention of “Mac Mac Cheese” nor “Eggy’s Omelettes” in the restaurant, but multiple signs for DoorDash, Uber Eats and Grubhub. The food was behind the counter in two generic plastic bags with no branding, something Mauriello said was done to save on costs. Two receipts with the names of the virtual brands gave the only indication that the food didn’t come from Palace Diner.

Though, of course, it also kind of did.