采用人工智能对心理健康的影响:自我效能的关键作用

作者:Lee, Julak

介绍

人工智能 (AI) 的出现改变了现代企业的运营、竞争和创造价值的方式(Budhwar 等,2017)。2022年;达文波特和罗南基,2018年)。人工智能的快速进步使企业能够简化复杂的流程,使以前的手动流程自动化,做出更好的决策,并使用更多的资源(Berente 等,2017)。2021年;布林约尔松和迈克菲,2017年;陈等人。2023年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。人工智能采用的成功取决于人为因素,包括预期与人工智能系统交互的工人的健康和适应性(Brock 和 von Wangenheim,2019年;马克里迪斯和汉,2021年;吴等人。2022年)。随着人工智能不断被纳入更多的组织职能中,这个问题变得越来越重要。

组织中人工智能的采用与人工智能技术在各种职能、流程和决策活动中的集成和部署有关(Dwivedi 等人,2017)。2019年)。组织越来越多地采用基于人工智能的系统、工具和算法来提高生产力、效率、创造力和竞争优势(Berente 等,2017)。2021年;达文波特和罗南基,2018年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。由于工人对于确保人工智能按预期工作并充分发挥其潜力至关重要,因此在工作场所实施人工智能之前,有必要充分理解人工智能将如何影响他们(Berente 等人,2017)。2021年;布林约尔松和迈克菲,2017年;陈等人。2023年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年;拉伊、康斯坦丁尼德斯和萨克尔,2019年)。

在组织内实施人工智能会对员工产生重大影响,影响他们的观念、态度、行为和整体福祉(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;布德瓦尔等人。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。因此,需要研究工人如何适应和管理人工智能带来的颠覆性变化(Glikson 和 Woolley,2020年)因为这些技术正在改变工作的性质和工人的角色。

应特别关注职业倦怠,因为它关系到人工智能部署背景下的员工福祉。倦怠的症状——情绪疲劳、人格解体和个人成就感减弱——及其对员工和组织的破坏性影响在现代工作场所非常常见(Maslach 等,2017)。2001年)。在工作场所引入人工智能可能会通过施加新的工作要求、改变工作特征和扰乱既定的工作惯例来加剧职业倦怠(Dwivedi 等,2017)。2021年)。由于担心工作保障,以及担心自己可能被人工智能取代,员工可能会承受更大的压力和倦怠(Brougham 和 Haar,2018年;吴等人。2022年)。

鉴于倦怠对员工福祉、组织生产力和人才保留的显着影响(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2017年),在人工智能采用的背景下调查倦怠的前因和机制至关重要。此类调查将使组织能够开发有针对性的干预措施和支持系统,以增强员工在人工智能驱动的工作环境中的适应力和福祉(Berente 等,2017)。2021年;陈等人。2023年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。

尽管学者们一致认为研究人工智能如何影响工人的重要性,但当前的文献仍存在许多空白。首先,很少有研究探讨人工智能的采用如何影响员工在工作场所的心理健康(特别是倦怠)(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;布德瓦尔等人。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年;马卡里乌斯等人。2020年)。此外,很少有实证研究探讨人工智能的采用如何影响员工的心理健康,尽管许多研究已经研究了人工智能部署的实际方面及其可能给组织带来的优势(Bankins 等人,2017)。2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。通过研究两者之间的相关性,可以获得关于人工智能采用对心理健康和减少人工智能驱动的工作场所倦怠的组织策略的不可预见影响的重要见解(Berente 等,2017)。2021年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。如果要在人工智能时代保障员工的福祉并确保组织的长期成功,鉴于当代工作场所中日益增多的心理健康问题以及人工智能可能会影响员工的健康,就必须填补这一知识空白。扰乱既定的工作模式和工作职责(Chen et al.2023年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年)。

其次,对人工智能采用与员工倦怠之间联系的中介者和调节者没有给予足够的重视(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;布德瓦尔等人。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。先前的研究主要关注人工智能采用对不同组织结果的直接影响,而忽略了影响人工智能采用和倦怠之间关系的复杂心理过程和边界条件。要全面了解人工智能采用与倦怠之间的关系,需要对中介变量进行调查,这些变量解释人工智能采用如何增加工作压力和倦怠(Budhwar 等,2017)。2022年;迈耶和许内菲尔德,2018年)。人工智能采用与职业倦怠之间关系的一个关键中介因素是工作压力,因为人工智能可以提高工作期望,使角色模糊性更加明显,并产生工作不安全感(Wu等,2017)。2022年)。通过研究工作压力作为中介的功能,这项研究试图揭示人工智能采用对心理健康的影响。

研究中的第三个差距与第二个差距密切相关,即研究人员尚未探索与自我效能相关的因素(例如对学习人工智能能力的信心)如何削弱人工智能采用对人们的有害影响。工作场所的心理健康(Bankins 等人,2017)2024年)。一个人的自我效能感(即对自己做好工作或应对挑战性情况的能力的信心;班杜拉,1986年),可以帮助工人应对工作场所压力(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2017年)。个人在人工智能学习中的自我效能感,定义为他们对自己获得和使用人工智能相关信息和技能的能力的信心,是人工智能采用领域的潜在保护因素,有助于减轻人工智能的负面影响- 对员工心理健康造成的压力(Nisafani 等,2017)2020年)。与其他员工相比,那些相信自己有能力学习人工智能的人可能能够更好地适应不断变化的工作需求,利用人工智能的机会,并感到自己负责和有能力,即使他们的工作已经被人工智能改变了。贝伦特等人。2021年;陈等人。2023年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。

需要进一步的实证研究来探索人工智能和倦怠之间的关系,因为尽管自我效能在理论和实践中都很重要,但很少有研究探讨自我效能在人工智能学习中的作用(De Vos et al.,2017)。2021年)。为了了解人工智能的采用如何影响工人的心理健康、哪些因素限制这种影响,以及如何在人工智能驱动的工作场所中提高工人的适应力和福祉,填补这一知识空白至关重要。

本研究以工作需求-资源(JD-R)模型和社会认知理论(SCT)作为补充理论框架,旨在填补这些研究空白。JD-R 模型提供了一个全面的框架,用于理解工作需求(例如与人工智能采用相关的需求)如何导致工作场所压力,并最终导致倦怠。它还强调了工作资源如何防止工作要求对员工健康和幸福产生不利影响(Demerouti 等,2017)。2001年)。JD-R 模型可用于检验工作压力作为人工智能采用和职业倦怠之间中介的作用,该模型提供了一个理论框架,该框架将人工智能采用视为一种职业要求,迫使工人学习新技能、适应不断变化的技术,并应对日益增长的复杂性和不确定性(Bankins 等人,2017)2024年;布德瓦尔等人。2022年)。

与 JD-R 模型一致,SCT 认为人们对自己能力的信念决定了他们对压力情况的反应、他们遇到的问题以及他们为克服这些问题而采取的行动(Bandura,1986年)。这项研究使用 SCT 来调查人工智能学习中的自我效能如何减轻人工智能采用对工作压力的不利影响。将 JD-R 模型与 SCT 相结合,展示了人工智能采用、工作压力、人工智能学习中的自我效能和倦怠如何相互作用。根据之前对组织心理学和人类与人工智能交互的研究,这是通过整合两种理论的优势来实现的(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;布德瓦尔等人。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。

本研究旨在回答以下研究问题:

-

1.

组织中人工智能的采用如何影响员工的倦怠?

-

2.

工作压力在调节人工智能采用和员工倦怠之间的关系中发挥什么作用?

-

3.

人工智能学习中的自我效能在多大程度上调节人工智能采用与工作压力之间的关系?

通过解决这些问题,我们试图全面了解人工智能采用、工作压力、倦怠和自我效能之间复杂的相互作用,因为它们与现代组织中的人工智能学习相关。

我们认为,由于多种原因,这项研究显着增强了有关人工智能采用和员工心理健康的文献。首先,它通过调查人工智能采用与员工倦怠之间的联系来填补知识空白。其次,它研究了工作场所的压力如何调节人工智能采用和职业倦怠之间的联系,阐明人工智能采用影响工人心理健康的心理途径。第三,通过强调个人特质在员工对人工智能相关工作要求的反应中的重要性,探讨了人工智能学习中的自我效能如何削弱人工智能采用对工作压力和工作倦怠的不利影响。最后,本研究通过整合 JD-R 模型和 SCT,推进了人工智能和组织心理学的理论和实践。它还提供了一个全面的理论框架,用于理解人工智能采用、工作压力和员工倦怠的复杂动态。

理论和假设

人工智能的采用和倦怠

我们建议组织中人工智能的采用会增加员工的倦怠。采用人工智能是一个复杂的多阶段过程,首先是提高认识和进行探索性研究,然后是大规模实施和持续改进(Kaplan 和 Haenlein,2020年)。需要对组织的准备情况进行全面评估,其中包括查看数据可用性、人力资本、领导支持、技术基础设施和公司文化等(Berente 等,2017)。2021年;陈等人。2023年;马吉斯特雷蒂等人。2019年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。组织需要对人工智能用例进行适当的优先级排序才能实现其战略目标(Davenport 和 Ronanki,2018年)。此外,人工智能技术引发的道德、社会和治理问题必须得到解决,以促进其负责任和透明的部署(Chen 等人,2017)。2023年;德维维迪等人。2019年)。为了充分利用人工智能并保持员工的敬业度和良好的照顾,组织必须调整策略,提供再培训和技能提升机会,并培养终身学习的文化(Magistretti 等人,2017)。2019年;马克里迪斯和米斯拉,2022年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。

工作中长期的人际压力会导致倦怠,这是一种由情绪疲倦、人格解体和个人成功感减弱所定义的精神状况(Maslach 和 Leiter,2016年;马斯拉赫等人。2001年)。人格解体的特点是对自己的工作和同事采取消极、冷漠和冷漠的态度,而情绪疲惫则涉及情感枯竭和过度扩张的感觉(Maslach 等,2017)。2001年;希罗姆和梅拉梅德,2006年)。自信心下降会导致对个人能力的不利评估,并最终导致对个人生活的不满(Maslach 等,2017)。2001年;莱特和马斯拉赫,2016年)。当一个人的情感和体力资源因工作环境不合适而耗尽时,就会出现倦怠(Leiter 和 Maslach,2003年)。研究表明,它会损害个人和组织的福祉。其中一些负面结果包括心理和身体健康、认知功能、工作满意度、组织承诺、离职意向、生产力、缺勤、医疗保健成本和服务质量等问题(Melamed 等,2017)。2006年;萨尔瓦吉奥尼等人。2017年;阿拉尔孔,2011年;李和阿什福思,1996年;巴克等人。2014年;塔里斯,2006年)。哈萨德等人。(2018年)发现,医疗保健成本、生产力下降和员工流失在很大程度上导致了职业倦怠,并造成了严重的财务后果。

根据 JD-R 模型、资源节约 (COR) 理论和技术压力模型,我们认为在工作场所采用人工智能会增加员工倦怠(Tarafdar 等人,2017)。2007年)。

首先,JD-R 模型指出,工作要求和工作资源是工作特征的两个主要类别,它们相互作用,影响员工的福祉结果,包括倦怠(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2017年)。工作要求需要工人的脑力和体力消耗,这可能会对他们的健康产生负面影响(Demerouti、Bakker、Nachreiner 和 Schaufeli,2001年)。采用人工智能可以被视为一种工作需求,因为它带来了新的问题和复杂性,要求员工获得新技能、适应新的工作流程并与人工智能系统协作(Makridis 和 Mishra,2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年;乌伦和爱德华兹,2023年)。此外,如果在工作场所实施人工智能系统,员工可能会感到压力,要求更快、更高效地工作(Berente 等人,2017)。2021年;陈等人。2023年),而压力和疲劳这两个倦怠的标志可能会因工作量的增加而恶化(Maslach 等,2017)。2001年)。由于工作要求,员工还可能面临额外的心理费用,例如需要不断学习和提高技能以保持其职业的相关性(Dwivedi 等,2017)。2021年;齐拉尔等人。2023年)。

二、COR理论(Hobfoll,1989年)支持人工智能采用与员工倦怠之间的联系。资源包括个人所看重的事物、特质、环境和精力;根据这一理论,人们努力工作来获取、保留和保护他们的资源(Hobfoll,2001年)。根据卡拉塞克(1979年)以及瑞安和德西(2000年),人工智能会削弱员工的资源,包括他们的信心、独立性和工作稳定性。如果员工因担心人工智能实施而失去这些资源而感到情绪和精神上疲惫不堪,他们可能会感到倦怠(Hobfoll,2001年)。

第三,技术压力模型(Taafdar et al.2007年)进一步阐明了技术采用与员工福祉之间的关联。技术压力是个人因在工作场所使用信息和通信技术 (ICT) 而承受的压力(Taafdar 等,2017)。2019年)。人工智能技术的采用可以被视为ICT实施的一个具体实例;因此,技术压力框架可用于了解人工智能对员工倦怠的影响。塔拉夫达尔等人。(2007年)确定了五个关键的技术压力创造者:技术超载、技术入侵、技术复杂性、技术不安全性和技术不确定性。这些技术压力的创造者可能会在人工智能采用过程中显现出来,导致员工压力和倦怠增加(Khedhaouria 和 Cucchi,2019年)。具体来说,当人工智能技术增加工作量并加快工作节奏,迫使员工更加集中地工作时,就会出现技术过载(Borle 等人,2017)。2021年)。技术入侵是指由于与人工智能系统相关的持续连接和可用性预期而侵蚀一个人工作和个人生活之间的界限(Taafdar 等,2017)。2007年)。当员工发现人工智能技术难以理解和使用时,技术复杂性就会出现,从而导致不足和沮丧的感觉(Tarafdar 等,2017)。2011年)。技术不安全感是对人工智能导致失业或失业的恐惧,而技术不确定性则表示人工智能技术的不断变化和升级,要求员工定期适应和获取新技能(Khedhaouria 和 Cucchi,2019年)。鉴于这些论点,提出以下假设。

假设1:组织中人工智能的采用会增加职业倦怠。

人工智能的采用和工作压力

本文表明,组织中人工智能的采用将增加员工的工作压力。工作压力是一个复杂的概念,涵盖了员工在面临难以应对的工作挑战时所表现出的精神、情感和身体反应(Lazarus 和 Folkman,1984年)。当人们在工作中面临巨大的压力、困难和要求时,可能会导致负面的身体反应和心理压力(Ganster 和 Rosen,2013年)。

我们建议,通过借鉴 JD-C)模型(Karasek,1979年)和人与环境(P-E)契合理论(Edwards 等,2016)。1998年)。

首先,根据JDC模型,工作压力是由工作要求和工作控制之间的相互作用引起的。工作量、时间限制和角色冲突都是员工在工作中面临的心理压力源的例子(Karasek 和 Theorell,1990年)。相反,工作控制被定义为工人在工作中行使代理权和能力的程度(Karasek,1979年)。根据 JD-C 模型,高工作要求加上缺乏对这些要求的控制,会增加与工作相关的压力(Häusser 等,2017)。2010年)。对人工智能在组织中广泛使用的一种解释是,它将增加对人类员工的要求。实施人工智能技术时,人员通常需要学习新技能、适应不同的工作流程并使用人工智能系统(Pereira 等人,2017)。2023年;齐拉尔等人。2023年)。当员工试图适应人工智能提出的新要求时,他们可能会发现自己受到更严格的时间和精力限制(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。当员工试图理解他们与人工智能相关的不断变化的职责时,人工智能系统的复杂性和不透明性也可能导致角色模糊和冲突(Bankins 等人,2017)。2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。

与此同时,人工智能的采用可能会让员工觉得他们对工作的控制力减弱。随着人工智能系统接管以前由人类执行的任务和决策角色,员工的自主权和决策权可能会减少(Budhwar 等人,2017)。2022年)。许多人工智能算法的不透明性质可能会进一步削弱员工的控制感,因为他们可能会发现理解和影响这些系统产生的结果具有挑战性(Shrestha 等人,2017)。2021年)。此外,当人工智能在工作场所实施时,个人可能会经历更大的工作压力,这与 JD-C 模型对更高的工作期望和更低的工作控制的描述一致。

其次,P-E 适合理论支持人工智能的采用会增加工作场所压力的观点。按照这种观点,只要个人的技能、需求和价值观等与工作场所的要求或提供不一致,压力就会产生(Edwards 等,2017)。1998年)。人工智能的广泛使用可能会导致工人当前的能力与技术所需的能力之间存在技能差距(Makarius 等人,2017)。2020年)。由于人工智能系统总是在不断发展并需要不断学习和适应,因此可能会出现技能差距,从而增加员工的压力(Nam,2019年)。采用人工智能的另一个问题是,它会让员工感觉自己的权力比实际的少(Pereira 等人,2017)。2023年)。员工可能会感到无能为力,因为他们对控制的渴望与工作环境的现实相冲突,特别是当人工智能接管决策并限制员工的自由裁量权时。根据 P-E 拟合理论,这种失调会加剧工作压力(Edwards 等,2017)。1998年)。

第三,社会技术系统理论(Trist和Bamforth,1951年)强调了人工智能的采用和工作压力之间的联系。该理论强调组织的社会和技术子系统必须保持一致,以提高员工绩效和福祉(Baxter 和 Sommerville,2011年)。人工智能的引入创建了一套新的工具、操作方法和决策标准(Vrontis 等,2017)。2022年)。如果社会子系统(包括工作职责、能力和人际关系等要素)没有根据新技术子系统进行适当调整,员工可能会发现他们的需求与人工智能增强的工作场所的需求发生冲突(Pereira 等,2017)。2023年;齐拉尔等人。2023年)。由于这种失调,员工在尝试适应新职位、学习必要技能以及应对人工智能采用的社会影响时可能会经历更大的工作压力(Shrestha 等,2017)。2021年)。

假设2:组织中人工智能的采用会增加工作压力。

工作压力和员工倦怠

根据 COR 理论,我们认为工作压力会增加员工的倦怠(Hobfoll,1989年),压力和应对的交易模型(TMSC;Lazarus 和 Folkman,1984年)和 JD-R 模型(Demerouti 等人。2001年)。

首先,根据 COR 理论,人们努力工作来获取、保留、捍卫和培育他们珍视的资源。个人所看重或帮助他们获得更重要资源的事物、品质、环境或能量都是资源的例子(Hobfoll 等,2016)。2018年)。当个人面临失去资源的风险、实际失去资源或在进行大量投资后未能获得资源时,他们会感到压力(Hobfoll,2001年)。工作场所压力可以被视为资源减少的一个条件。根据巴克和德梅鲁蒂的说法(2017年),工人承受着很高的工作压力,因为他们被要求用更少的资源做更多的事情。情绪和身体疲劳以及精神压力可能是资源枯竭的迹象(Alarcon,2011年)。在压力条件和资源匮乏的情况下长期工作后可能会出现倦怠(Hobfoll 等人,2017)。2018年)。

其次,根据 TMSC 的说法,当人们感觉自己缺乏满足场景需求所需的应对资源时,就会感到压力。这表明认知评估和应对机制是个人经历压力的交易过程的组成部分(Lazarus,1999年)。与那些不相信自己的工作量超过其应对能力的员工相比,工作场所压力更常见(Goh 等人,2017)。2015年)。倦怠的重要组成部分是长期暴露在工作压力下造成的身体、情感和精神耗竭(Maslach 等人,2017)。2001年)。根据 TMSC 的说法,当员工的情感和认知资源因无法应对工作压力而耗尽时,就会出现倦怠(Guthier 等,2017)。2020年)。这与 COR 理论的假设一致,即资源的枯竭和损失会导致倦怠(Hobbow 等人,2018)。

第三,JD-R 模型显示了工作压力如何导致倦怠。工作要求和工作资源是工作特征的两个主要分支(Demerouti 等,2017)。2001年)。工作要求包括工作的社会、组织和体力要求因素,这些因素会导致一个人随着时间的推移而产生生理和心理费用(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2007年)。工作场所的要求包括高度的情绪和精神压力以及时间限制(Bakker 等,2017)。2014年)。同时,工作资源是工作的身体、心理、社会和组织部分,可帮助工人实现目标、应对压力以及职业和个人发展(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2007年)。社会支持、自主权和绩效评估是工作资源的例子(Van der Heijden 等,2017)。2019年)。JD-R 模型预测了工人的压力和倦怠,该模型指出,当工作要求高而工作资源低时,工人更有可能经历前者(Demerouti 等人,2017)。2001年)。倦怠的特征是情绪、精神和身体上的疲劳;它可能是由工作压力引起的,这种压力发生在需求高而资源稀缺的情况下(Maslach 等,2017)。2001年)。

假设3:工作压力会增加倦怠。

工作压力在人工智能采用与职业倦怠关系中的中介作用

研究工作压力如何调节组织中人工智能的采用与职业倦怠之间的关联是本研究的主要目标之一。通过结合 JD-R 模型、COR 理论和 TMSC,我们预计工作压力将在人工智能采用-倦怠环节中发挥中介作用。

首先,员工福祉和组织成果受到工作需求和工作资源之间相互作用的影响,根据 JD-R 模型进行分类(Bakker 和 Demerouti,2017年)。组织中人工智能的采用将需要更多的人学习和适应新技术,需要完成更多的工作,并且可能会产生更多的角色模糊性(Bankins 等,2017)。2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。JD-R 模型假设,当工作需求超过可用资源时,可能会出现倦怠和其他负面影响。

其次,根据 COR 理论,工作压力会调节人工智能采用与职业倦怠之间的联系。根据这一理论,人们努力工作以获得他们想要的东西并保留他们所拥有的东西(Hobfoll 等,2017)。2018年)。工人的信心、独立性和工作稳定性都是人工智能的引入可能危及的资源。如果员工担心人工智能集成会消耗他们的资源,他们可能会感到情绪和精神上的疲惫和倦怠(Hobfoll,2001年)。

最后,TMSC 进一步解释了工作压力作为人工智能采用和职业倦怠之间的中介作用。这种范式提出,当人们面临挑战时,比如采用人工智能,他们会进行认知评估,以确定挑战的严重程度以及他们拥有哪些资源来应对挑战(Lazarus 和 Folkman,1984年)。如果员工担心人工智能的采用可能会损害他们的工作稳定性、工作身份或良好执行工作的能力,并且如果他们认为自己无法处理这些问题,他们可能会感到更大的工作压力。如果员工经常承受无法应对的压力,他们可能会感到倦怠。

根据上述论点,我们提出以下假设。

假设4:工作压力会调节组织中人工智能的采用与倦怠之间的关联。

人工智能学习中自我效能感对人工智能采用与工作压力之间联系的调节影响

我们假设,个人对人工智能学习能力的信心会削弱人工智能的采用对工作压力的日益增加的影响。在这种背景下,人工智能学习中的自我效能是一个人对自己学习人工智能和使用人工智能的能力的信心(Bandura,1977年)。更具体地说,这种特定于上下文的构造表示一个人对自己与人工智能系统交互、理解人工智能思想和有效使用人工智能工具的能力有多大信心(Kim 和 Kim,2024年)。人工智能学习中的自我效能概念源于班杜拉的SCT(Bandura,1986年)。该理论认为,一个人如何看待自己的才能会影响他们在某个领域的动机、行动和成就。一个人对自己学习人工智能能力的看法会影响人们准备投入多少时间和精力来完成人工智能相关任务、他们处理挫折的能力以及他们实践所学知识的效率(Kim 和 Kim,2024年)。

通过深入研究员工自我效能感在人工智能学习中的调节作用,可以更好地理解人工智能采用与员工工作压力之间的联系。基于 TMSC 和 SCT,我们建议,如果员工相信自己理解和利用该技术的能力,那么采用人工智能对工作压力的影响将会减弱。

首先,SCT 提出,个人的自我效能——他们对自己采取行动以实现预期结果的能力的信心——强烈影响他们的推理、动力和情感(班杜拉,1997年)。“人工智能学习中的自我效能”一词在人工智能采用的背景下使用,用于描述员工对其获取和使用人工智能相关知识和技能的能力的信念(Bandura,1986年)。自我效能感较高的人压力较小,更倾向于将挫折视为学习经历,并且更愿意在逆境中坚持下去(Bandura,1997年)。此外,TMSC阐明了自我效能感如何进入压力评估(Lazarus and Folkman,1984年)。根据该模型,人们在面对可能的压力源(例如在工作中实施AI)时进行认知评估,以确定情况的严重性以及他们能满足的程度(Lazarus and Folkman,1987年)。关于AI,对学习和适应新技术的能力有信心的员工很可能将AI的采用视为他们可以完成的任务,而不是压倒性的危险。

在人工智能学习中具有高度自我效能的工人也对自己有效学习和使用AI的能力有信心(Bandura,1997年)。根据SCT的说法,该小组更有可能将AI广泛使用为专业和个人发展而不是危险的机会(Bandura,2012年)。这些工人一直在寻找提高知识和能力的新方法,并迅速采用新技术(Chae等。2019年)。与不持有这种信念的人相比,人们相信自己学习AI的能力的工人可以更好地管理AI采用的要求。

此外,TMSC(Lazarus and Folkman,1987年)建议这些人可以在主要评估过程中感知AI作为可管理的压力源,因为他们对获得与AI合作所需的基本能力充满信心。他们的应对资源,包括AI学习能力,在次级评估过程中可能被认为是适当的,以满足情况的需求。对学习人工智能能力有信心的工人相对不太可能受到在工作场所采用AI的威胁。这是因为他们对自己从过程中适应和获利的能力充满信心。

例如,如果组织使用AI为CRM系统供电,那么在人工智能学习中具有高度自我效能的工人可以将情况视为磨练其客户服务技能的机会,同时也有效地使用AI提供的数据为每个人提供独特的相遇客户。这些工人还将更倾向于参加培训计划,在需要时寻求帮助,并尝试使用新的CRM技术来发挥其全部潜力。此外,他们可以比其他工人更适合新技术,因为他们积极寻求资源来发展其AI能力并从事积极的学习活动。结果,他们不必过分担心无法满足期望,并且对使用AI驱动的CRM系统的能力充满信心,以提高公司的业绩。

当工人缺乏理解和利用与AI相关信息的能力的自我效能时,这种情况就会逆转(Bandura,1997年)。SCT声称,由于他们的焦虑和紧张局势,这些人更容易将AI采用视为对工作安全和能力的威胁(Bandura,2012年)。他们可能会以防止他们学习,抵抗学习机会并难以适应新技术(Charness and Boot,2016年)。此外,不相信学习AI能力的工人可能会努力应对AI实施的挑战。结果,当公司实施AI系统时,这些工人可能会感到压力很大,因为他们不准备应对不可避免地会出现的新职责和障碍。

TMSC的建议支持了这一点,即对获得AI的能力缺乏信心的员工很可能将AI的收养视为一项压力很大的事件,他们在主要评估过程中无法管理,Lazarus and Folkman,1987年)。他们可能会得出结论,他们的应对资源,尤其是他们的AI学习能力,在次级评估过程中处理情况的需求不足。对学习AI的能力缺乏信心的人会增加工作场所的压力,适应组织的AI采用实践的困难以及对公司在公司未来的不确定性(Cankins等。2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。

例如,那些不擅长学习如何使用AI的员工会被组织安装的新CRM工具吓倒。他们可能会抵抗培训课程,犹豫不决使用新的客户关系管理系统,并担心将工作失去工作(Meyer和Hã¼nefeld,2018年)。结果,这些工人会在工作中感到增加的压力,因为他们担心无法实现AI驱动的CRM系统设定的新标准及其无法适应的标准。

以下假设基于上述理论考虑:

假设5:人工智能学习中的自我效能感会减轻组织中AI的采用与工作压力之间的联系,以使AI的采用和工作压力之间的积极关联对于AI学习中具有较高自我效能的员工而言,与自我较低的人相比功效。

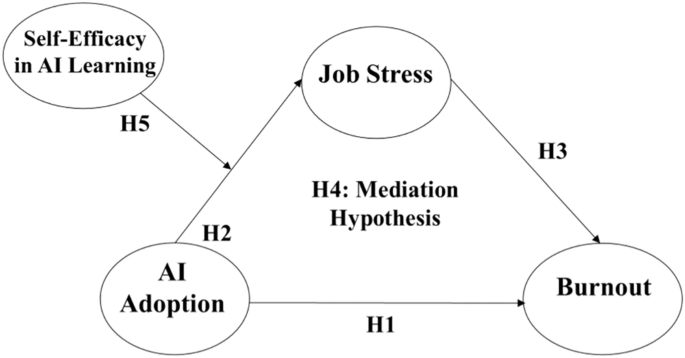

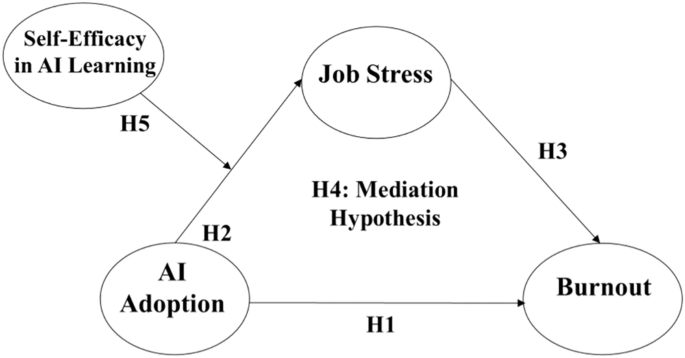

数字1说明了本研究中使用的概念模型,该模型描述了AI采用,工作压力和倦怠之间的假设关系,以及自我效能感在AI学习中的调节作用。

方法

参与者和程序

来自不同公司的一群在韩国20多岁以上的成年人参加了本研究。使用了三波滞留的研究设计,其中参与者参加了三个单独的时间。一个著名的互联网研究组织,有约545万人的受访者支持招聘过程。要求参与者在线注册时验证其工作状态,该平台使用其电子邮件地址或手机号码确定了参与者。早期研究的证据支持使用在线调查来吸引人口的代表性样本(Landers and Behrend,2015年)。

横断面研究方法的限制是通过在三次分开的三次从韩国组织中积极雇用的人那里收集的数据来解决的。研究人员使用数字基础架构来监控参与者参与调查的方式。这有助于确保在整个研究中参与保持一致。以五和六周的间隔收集数据,每个调查窗口为两三天,因此为受访者提供了足够的时间来完成调查。该组织使用地理IP限制陷阱和其他数据完整性保护措施来检测和防止过快的答案,从而保持了研究结果的高质量。

调查公司邀请注册人参加这项研究。研究人员向潜在的参与者保证,他们的参与是可选的,并承诺将参与者的答案私密,并仅用于研究目的。所有参与者都给予了知情同意,我们遵循了所有适用的道德准则。经济激励措施从$ 8.00 $ 9.00提供给参与者。

研究人员使用分层随机抽样来根据人口和职业因素(例如年龄,性别,教育水平和行业)从几个阶层中随机选择队列。这有助于最大程度地减少采样偏差。该调查公司跟踪了几个数字平台上的受访者互动,以确保同一个人参与了民意调查的所有三波。

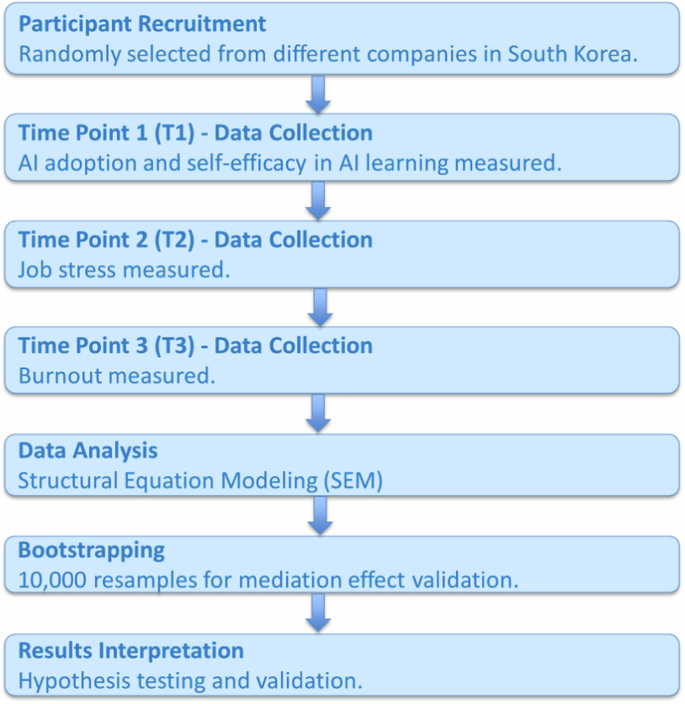

在这三波波浪中,803名工人参加了第一波,在第二波中回答了571个,而第三波中有418个回答。最终数据集未包含不包含所有必要信息的调查。填写所有三个问卷的416名参与者(占总数的51.81%)包括该研究的最终样本(请参阅表1)。G*功率用于统计分析,以及Barclay等人的提议。(1995年)遵循每个变量至少10个实例,从而计算样本量。数字2介绍了本研究中采用的方法的流程图,说明了我们研究过程的顺序步骤,从参与者招聘到数据分析。

措施

首先,收集了与AI采用和自我效能相关的数据。参与者报告了第二个时间点的工作压力水平。有关倦怠严重程度的信息是在第三个间隔收集的。我们使用5点李克特量表与多个项目来评估每个变量。

AI采用(工人报告的时间1,时间1)

我们使用了从早期研究中建立的量表修改的五个项目来衡量组织中AI采用的水平(Chen等。2023年;程等人。2023年;潘等人。2022年)。具体而言,使用了以下项目:我们的组织在其人力资源管理系统中使用人工智能技术,我们的组织在其生产和运营管理系统中使用人工智能技术,”我们的组织在其营销和客户管理系统中使用人工智能技术,在我们组织的战略和规划系统中使用了人工智能技术。人工智能技术用于我们组织的财务和会计系统。据报道,Cronbach的α值为0.949。

人工智能学习中的自我效能(时间1,工人报告)

我们从先前的研究中使用了四项量表,该量表适应了Bandura的自我效能感量表,以用于AI学习(Bandura,1986年)。该量表是由先前的研究(Kim and Kim,Kim,2024年)。考虑了以下项目:我对自己在工作中适当学习人工智能技术的能力充满信心,即使情况是,我也能够学习人工智能技术以表现出色具有挑战性,我可以通过AI技术学习来发展工作所需的能力,并且我将能够从AI中学习重要的信息和技能培训。报道了Cronbach的α值为0.936。

工作压力(时间2,工人报告)

调查包括工作应力量表的六个项目,这些项目是通过修改先前量表开发的(Dejoy等。2010年;Motowidlo等。1986年)测量工作压力。利用的项目包括以下内容:``由于我的工作,我感到很大的压力 - 我在工作中经历了许多压力大事,我的工作很紧张,”我对工作感到沮丧,•我在工作上感到紧张或焦虑,”我感到生气或工作中受刺激的刺激。据报道,克朗巴赫的α值为0.913。

倦怠(工人报告的时间3,时间3)

Maslach倦怠库存中的六个项目(Maslach等。1997年,2001年)用于评估员工倦怠的严重性。所使用的项目包括以下内容:``我从工作中感到情绪化,'当我下班回家时,我在精神上和身体上精疲力尽,'我觉得我工作在精神上和身体上消耗了我的精力,我对自己的工作变得不那么热情,'我觉得我的工作达到了极限,当我早上起床并在工作中面对另一天时,我感到很累。克朗巴赫的alpha值为0.891被举报。

控制变量

我们将员工任期,性别,职位和教育作为控制变量,因为先前的研究表明这些因素可能会影响倦怠(Maslach等。1997年,2001年)。我们在第一次调查中收集了这些控制变量的数据。文献表明,在研究倦怠时,包括性别,教育水平,职位和任期为控制变量。这些控制变量被认为可以帮助我们更清楚地解释主要变量,并减少省略变量引起的偏见。

统计分析

收集数据后,在SPSS 28软件套件中进行了Pearson相关分析,以研究研究变量之间的连接。根据安德森(Anderson)和格林(Gerbing)提出的两阶段程序(1988年),研究技术融合了一个测量模型和结构模型。验证性因素分析(CFA)用于验证测量模型。之后,使用AMOS 26软件的调解模型分析检查结构模型,并根据SEM原理使用ML估计方法。

使用了几个拟合指数来评估模型与经验数据匹配的程度。其中包括比较拟合指数(CFI),塔克·刘易斯指数(TLI)和近似的均方根误差(RMSEA)。CFI和TLI高于0.90的值以及RMSEA低于0.06的值是可以接受的,这与学术界的规范一致。通过利用95%置信区间(CI)来解释偏差,该置信区间是使用自举方法计算的,从而支持了调解假设。根据Shrout和Bolger的说法,非零的CI意味着在0.05水平上具有统计学上显着的间接效应(2002年)。

结果

描述性统计

我们的发现揭示了AI的采用,AI学习,工作压力和倦怠之间的牢固关系。桌子2显示分析的发现。

测量模型

我们使用CFA检查了测量模型的合适性和四个主要研究变量的判别有效性。使用卡方差异测试将四因素模型与各种替代模型进行了比较。这些模型包括三因素模型( -2(dfâ= 184)= 1792.555,cfi = 0.760,tliâ= 0.727和rmsea =rmseaâ=â= 0.145),两个-Factor模型( -2(dfâ= 186)= 3102.000,cfi = 0.566,tliâ= 0.510和rmsea = rmsea =â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â=â= 0.194)和a一因子模型( -2(dfâ= 187)= 4431.832,cfi = 0.368,tli = 0.290和rmsea = 0.234)。实施了一系列卡方差异测试以找到最佳模型。四因素模型的拟合指数表明具有较高的拟合度,具有卡方值(dfâ=â181) - = 395.219,CFI = 0.968,tli =0.963,RMSEA = 0.053。四因素模型正确区分了研究变量。

结构模型

我们使用构建的调节中介模型测试了我们的假设。这个概念包含调解和节制的要素。工作压力是AI采用和倦怠之间的调解人,而在AI学习中的自我效能减少了AI采用对工作压力的影响。

通过将AI学习的两个变量和自我效能感的两个变量乘以AI学习中的两个变量,从而生成了相互作用项。在创建交互项以解决潜在的多重共线性之前,我们将含义为中心的变量。Brace,Kemp和Snelgar(2003年)发现中心过程有助于降低多重共线性并防止相关性减少,从而增强了节制分析的有效性。

Brace等。(2003年)建议计算方差通胀因子(VIF)值和公差,以评估可能的多共线性。AI学习中的AI采用和自我效能感为0.967的耐受性指数的VIF值为1.034。因此,数据表明AI中的AI采用和自我效能感不受多共线性的影响。这是由超过0.2和VIF值低于10的公差值支持的(Brace等。2003年)。

调解评估的结果

最好的拟合模型是通过使用卡方差异测试将部分中介模型与完整中介模型进行比较来确定的。部分和完整的调解模型之间的唯一区别在于,后者不包括AI采用和倦怠之间的因果关系。两种型号均显示出良好的适合指数,并带有 -2= 501.018(dfâ= 212),cfi = 0.948,tliâ= 0.938和rmsea =rmseaâ= 0.057模型和 -2= 500.972(dfâ= 211),cfi = 0.948,tliâ= 0.938和rmseaâ=rmseaâ= 0.058模型。

但是,模型之间的卡方差异(歧程 -2[1] = 0.046,p> 0.05,非显着)证明了完整的调解模型更合适。这一发现意味着AI的采用率会通过工作压力间接影响倦怠,而不是直接影响。这项研究结合了与倦怠有关的控制变量,包括性别,教育水平,职位和任期。除任期外,所有控制因素在统计上都微不足道( -= 0.097,p<0.05)。

假设1被拒绝,因为部分调解模型表明,组织中的AI采用与倦怠无关( -= 0.010,p> 0.05)。局部调解模型具有不重要的系数,该模型显示了AI采用和倦怠之间的直接相关性巩固了对完整调解模型的偏好,该模型已获得批准。该结果以及改进的拟合指数证实了完整的调解模型比部分的模型更好。因此,我们拒绝了假设1,并得出结论,就业压力是AI采用和倦怠之间的调解人。

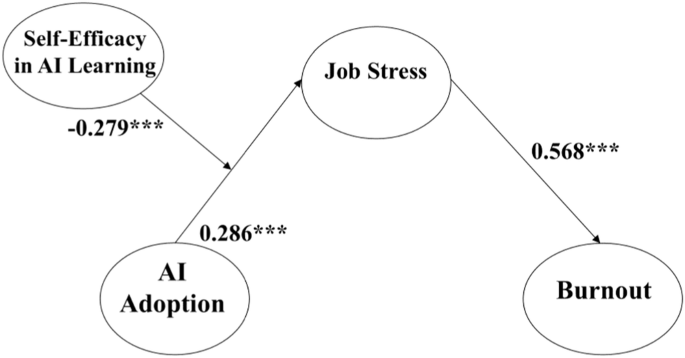

假设2指出,AI的采用显着增加了工作压力( -= 0.286,p<<0.001),假设3指出,工作压力显着增加了倦怠( -= 0.568,p<<0.001)。结果证实了这两个主张(见图。3和表3)。

自举

遵循Shrout和Bolger报告的方法(2002年),我们使用了一项以10,000个样本量为10,000的自举技术来检验假设4,该技术指出工作应力介导了AI的采用和倦怠之间的关联。Shrout和Bolger的建议(2002年)指出,为了使平均间接效应具有统计学意义,95%偏置校正的CI不得包括0。

这项研究采用了一种自举方法来研究工作压力对AI采用和倦怠之间联系的调解作用,如假设4所示。如果平均效应的95%偏差校正CI,调解效应将被认为具有统计学意义。不是0。工作压力是一个具有统计学意义的中介者,因为数据证明了CI排除0(95%CI = [0.102,0.230])。因此,假设4被接受。桌子4从AI采用到倦怠,包括直接,间接和全面影响,介绍了整个路径。表4最终研究模型的直接,间接和总影响。

这项研究旨在确定一个人对学习AI能力的信念是否会影响AI采用和工作压力之间的关系。

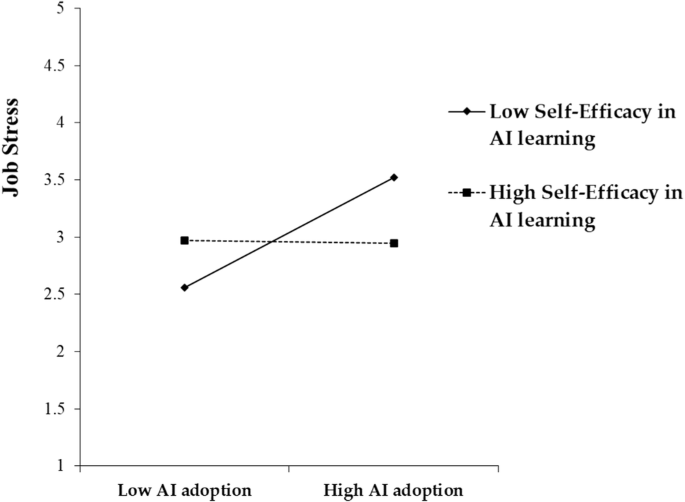

通过将变量AI的采用和自我效能在AI学习中构建互动术语来检查这一点。检查表明该相互作用项具有统计学意义( -= 0.279,p<<0.001)。这一发现表明,一个人对学习AI的能力的信念是主持人,从而削弱了AI采用对工作压力的影响。该结果支持假设5(图。4)。

讨论

这项研究旨在回答有关AI在工作场所中采用,工作压力和倦怠之间的关联的几个问题,以及在AI学习中作为主持人的自我效能。面对技术变革,希望管理成员福祉的组织应考虑工作中AI采用的心理后果。这项研究为这些含义提供了重要的见解。

表中列出的发现5在几个关键领域与以前的研究保持一致并扩展。例如,基于Bancins等人的评论。(2024年),我们对通过工作压力对AI采用对倦怠的间接影响的发现,以及对AI学习中自我效能的关注,对Marikyan等人的工作进行了补充。(2022年)关于人类的合作。此外,我们对自我效能作为调节因素的调查基于Ding等人(2021年)探索工人对AI的态度。此外,我们的研究通过在全面的框架中研究AI学习中的AI采用,工作压力,倦怠和自我效能感之间的联系,从而为文献做出了贡献,从而在组织AI的背景下为这些关系提供了对这些关系的更加细微的理解。

假设1提出,在组织中采用AI会增加员工的倦怠。但是,结果不支持这一假设,因为AI采用和倦怠之间的直接关联不是重要的。鉴于人们对AI对员工福祉的潜在有害影响的关注日益关注,这一发现令人惊讶(Dwivedi等。2021年)。然而,该结果突出了考虑AI采用可能影响员工结果的复杂机制的重要性,而不是假设简单的直接关系。

假设2预测,在工作场所实施AI将增加工人的工作压力。根据JD-R模型,高工作需求,例如可以通过AI采用产生的工作,可以产生压力,而当前的发现与该理论一致。AI可以通过为工人解决新问题而增加工作场所的压力,例如需要学习新技术,对职责的不确定性和增加工作量(Brougham and Haar,Haar,2018年)。

这些发现还支持假设3,这表明工作压力会增加员工的倦怠。这一发现符合JD-R的说法,即倦怠和疲倦可能是长期暴露于压力大的工作环境的结果(Bakker和Demerouti,2017年)。员工可能更容易出现倦怠症状,例如情绪疲倦,犬儒主义和个人成就减少,这是由于AI采用引起的工作压力增加(Maslach等。2001年)。

此外,结果支持假设4,该假设4假设工作压力介导了AI的收养与员工倦怠之间的关联。采用AI并没有直接影响倦怠,但它通过增加的工作压力会大大影响倦怠。这一结论凸显了研究AI的实施如何影响员工的福利的重要性。采用AI会增加压力水平,这可能会导致倦怠,因为它会在工作场所产生新的需求和挑战。

根据假设5,在AI学习中具有较高自我效能感的员工在AI采用和工作压力之间表现出较不积极的联系。预计该链接将通过AI学习中的自我效能来调节。结果表明,AI学习中的自我效能减轻了AI采用对工作压力的提高作用,从而支持了这一假设。SCT的基本思想与这一发现一致,因为它突出了自我效能感在塑造人们对困难和压力的反应方面的力量。与其他工人相比,具有高水平的自信心的工人可能认为AI的实施不那么艰巨,更可控制,从而减少了AI实施是压力的根源。

理论意义

当前的论文具有一些至关重要的理论含义。首先,本文通过将JD-R模型与SCT相结合,提供了一个彻底的理论框架,以理解AI采用与员工倦怠之间的复杂关系。JD-R模型为研究工作压力的功能提供了一个极好的起点,作为AI采用和倦怠之间的主持人,因为它认为资源和工作需求与组织成果和员工福祉相互作用(Bakker and Demerouti,Bakker and Demerouti,2017年)。这项研究将JD-R模型的适用性扩展到AI采用的背景下,通过对将AI采用与倦怠联系起来的心理机制有细微的了解。它通过将AI采用概念化为独特的工作需求来实现这一目标,要求员工适应新技术,获得新技能并管理增强的复杂性和不确定性(Chen等。2023年;德维维迪等人。2021年;Makridis和Mishra,2022年;Uren和Edwards,2023年)。

此外,这项研究通过考虑SCT来提供有关自我效能感的调节作用的新观点,该研究强调了自我效能感对人们的信念,行为和应对机制的影响(Bandura,Bandura,1986年)。根据SCT的说法,一个人的自我效能感(即,对完成任务的能力的信心)对一个人的目标设定,压力管理和挑战策略的影响最大(班杜拉,1997年)。这项研究通过强调AI学习中的自我效能是一种个人资源,可以缓解AI采用对员工福祉的有害影响,从而扩展了SCT对AI采用和员工韧性的适用性。JD-R模型和SCT的整合提供了一种整体理论观点,可以理解AI采用,工作压力,自我效能和倦怠之间的复杂相互作用,从而增强了组织心理学中的理论发展。

其次,通过将AI的采用视为独特而多方面的工作需求,这项研究增加了有关工作需求和资源的文献。这项研究调查了AI采用的需求,其中包括学习和适应新的AI技术,管理人AI协作的复杂性,并解决有关AI如何影响工作角色和职责的不确定性。现有的作品研究了技术采用对员工福祉的影响(例如,迈耶和hã¼nefeld,2018年)。这项研究通过对与AI相关的工作需求及其影响进行全面分析,从而增加了知识体系。它还突出了在评估AI技术对员工福祉的影响时考虑AI技术的不同特征的重要性。对AI特异性需求的重要性以及它们如何影响员工压力和倦怠的理解对于组织心理学和AI采用的理论进步至关重要(Makarius等。2020年)。

第三,这项研究通过强调了AI学习自我效能作为主持人在AI采用和工作压力之间的关联中的重大影响,从而增加了有关个人资源和员工韧性的文献。当前的研究探讨了AI学习自我效能感的作用,这是与AI采用有关的新鲜且相关的个人资源。现有作品已经承认个人资源在减少工作需求对工人福祉的有害影响方面的重要性(例如,Xanthopoulou等。2007年)。当前的研究通过表明对学习AI的能力有强烈信念的员工可以应对与AI采用相关的困难和期望,从而为SCT的文献做出了贡献。因此,组织可以通过提高自我效能感的AI培训和发展计划来减少AI采用对幸福感的负面影响,并提高员工的韧性(Pillai和Sivathanu,2020年)。除了具有实质性理论含义外,这一发现还强调了对AI采用和员工福祉之间关联的进一步研究的重要性,因为它与其他个人资源(如韧性和适应性)有关。

第四,这项研究通过对AI采用,工作压力和倦怠之间的关联进行了首次经验检查,从而增加了有关AI在工作场所中采用心理健康影响的文献。研究表明,从理论角度来看,AI的采用可能会影响工人的福祉(例如,Cankins等。2024年;Budhwar等。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。但是,我们的研究通过提供经验证据来介导AI采用和倦怠之间的关联来增加文献。这项研究通过表明采用AI可以增加工作压力,从而对AI和倦怠之间关系的心理过程提供了详细的解释,这反过来又增加了倦怠。基于现有作品(Bashins等。2024年;Budhwar等。2022年;Glikson和Woolley,2020年),这一发现具有重大的理论意义,并强调了组织需要优先考虑员工的福祉,并主动应对与AI实施相关的心理挑战。这项研究还要求对AI采用对组织成果和工人福祉的长期影响进行更多研究(Pereira等。2023年)。它还强调需要考虑采用AI对工人心理健康的意外后果。

实际意义

我们的结果需要由高层管理团队,领导者和从业人员仔细解释,因为他们可能具有重要的实际含义。

首先,当前的研究强调了优先考虑员工福祉并主动解决与AI采用相关的心理问题的重要性。它还强调了将以人为本的策略采用AI部署的重要性(Budhwar等。2022年;Glikson和Woolley,2020年)。因为实施AI可以使工人对工作更加焦虑,并且更有可能经历倦怠,因此公司需要制定计划,以帮助员工在实施AI时保持精神健康和韧性。公司可以通过创建一个欢迎所有员工,有压力管理班以及员工感到安全地说出自己的思想的环境来帮助缓解工人对AI的担忧(Budhwar等。2022年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。

领导者和高层管理人员还应通过要求他们的思想和意见来确保该技术是针对工人的能力,期望和要求来量身定制的,还应通过提出他们的思想和意见来吸引工人对AI采用的意见(Bashins等。2024年;Rai等。2019年)。企业可以通过使他们参与决策并允许他们塑造AI采用的道路(Meyer andHã¼nefeld,ai,企业,可以帮助员工应对AI对福祉的有害影响。2018年)。领导者应该在AI采用过程中对员工开放和诚实,包括其目标,优势和可能的障碍。他们还应该让员工知道正在采取哪些步骤来支持他们。Workers’ worries about how AI may affect their jobs and responsibilities can be allayed through open and honest dialogue that fosters trust and minimizes uncertainty.

Second, this study highlights the significance of AI training and development programs in boosting members’ self-assurance in their AI learning capabilities. This, in turn, will mitigate the harmful influences of AI adoption on stress and burnout in the workplace. Companies should put money into AI training programs that teach workers how to use AI effectively but also how to have a growth mindset and believe in themselves so they can thrive in a workplace driven by AI. Training programs should be designed with various employee groups’ needs and ability levels in mind, thus providing a safe space for learning that promotes trying new things, receiving and acting on feedback, and constant improvement (Dwivedi et al.2021年)。Furthermore, companies should help people maintain and improve their AI abilities over time since employees need to constantly learn and adapt to new technologies (Bankins et al.2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。Such efforts might include online learning platforms, chances for employees to learn from each other and share their knowledge, and rewards for employees who put in the effort to become AI-competent (Berente et al.2021年;陈等人。2023年;Meyer and Hünefeld,2018年)。Organizations that put money into AI training may assist their workers in thriving in a world where AI is the driving force behind many commercial decisions.This will boost their confidence in their capacity to master AI and encourage a growth mindset.

Third, the literature stresses the significance of aligning AI system design and implementation with employees’ requirements, competencies, and well-being (Glikson and Woolley,2020年)。Organizations can lessen AI’s negative impact on worker stress and burnout by making sure the technology works in tandem with human talent rather than trying to supplant it (Makarius et al.2020年)。In order to accomplish this, organizations must perform comprehensive job assessments (Rai et al.2019年) to identify processes and jobs that can be automated by AI and the abilities that workers will need to collaborate successfully with these systems. Furthermore, organizations should prioritize the health and well-being of their employees while developing AI systems. This includes adding capabilities that lessen the cognitive load, simplify processes, and supply the tools and resources needed to handle the demands of human–AI collaboration. Methods for dealing with AI-related mistakes or outliers should be clearly defined, and user-friendly interfaces should be implemented (Bankins et al.2024年;德维维迪等人。2021年)。Firms can foster a more positive and empowering work environment for their employees by developing AI systems that are tailored to their needs and skills.

Fourth, research stresses the need to continuously assess how AI implementation affects worker’s well-being and organizational outcomes (Oksanen et al.2022年)。Organizations must regularly evaluate their AI implementation and make any required adjustments to keep up with the ever-changing AI landscape and make sure their strategies meet the needs of employees and the company (Bankins et al.2024年)。This may require key performance indicators pertaining to creativity, quality, and productivity to be monitored and frequent surveys and focus groups with employees to be conducted to understand their thoughts on how the adoption of AI is affecting their well-being, stress, and burnout (Pillai and Sivathanu,2020年)。In addition to measuring the technical performance of AI systems and their effect on employee engagement and well-being, organizations should set clear benchmarks to assess the success of their AI initiatives (Makarius et al.2020年)。Organizations can improve their AI strategies, make data-driven decisions about future investments, and identify areas for improvement by regularly monitoring and assessing the impact of AI adoption.

未来研究的局限性和建议

Although this paper enhances the knowledge of AI adoption’s impact on employee well-being, it has certain limitations that present opportunities for further research in this field. First, although this study uses three-wave time-lagged data, it is fundamentally cross-sectional, which makes it difficult to draw any causality concerning AI adoption, job stress, and burnout. To better understand how these connections change over time, future research should use longitudinal techniques. By doing so, researchers can better explain the long-term effects of AI adoption on employee well-being and investigate potential reciprocal relationships between job stress and burnout.

Secondly, common method bias may have affected the results because the study utilized self-reported measures of job stress and burnout (Podsakoff et al.2003年)。Future research should make use of objective metrics like cortisol levels, which are physiological markers of stress, or ratings given by supervisors, which are third-party evaluations of burnout.A combination of methods would be preferable for ensuring a more thorough evaluation of the mental and behavioral effects of AI implementation (Bankins et al.2024年;佩雷拉等人。2023年)。

Third, while this study examined the mediating role of job stress in the relationship between AI adoption and burnout, it did not explore the specific job demands and resources that contribute to job stress in the context of AI adoption. Future research should investigate unique demands (e.g., techno-complexity, techno-uncertainty) and resources (e.g., AI-related training, technical support) in AI-driven work environments (Brougham and Haar,2018年)。Identifying key job characteristics that shape employees’ stress and burnout would enable organizations to develop targeted interventions to mitigate AI adoption’s harmful influence on well-being.

Fourth, this research examined how self-efficacy in AI learning can decrease the detrimental influences of AI adoption on burnout and stress on the job. Employees’ reactions to AI adoption may be impacted by other human qualities, like openness to new experiences and resilience (Khedhaouria and Cucchi,2019年)。To better understand the factors that contribute to employee resilience and well-being in AI-enabled environments, future research should explore additional personal resources and individual differences in the relationships between AI adoption, job stress, and burnout (Meyer and Hünefeld,2018年)。

Fifth, this study did not cover the possible benefits of AI adoption, such as enhanced productivity, innovation, and employee engagement. It is critical to address the problems and unforeseen effects of AI adoption, but it is just as important to look at the possibilities and advantages that AI technology can offer to organizations and their workers (Glikson and Woolley,2020年)。Future research on the effects of AI adoption on organizational performance and employee well-being should follow a nuanced approach that considers both the upsides and the downsides of AI adoption.Organizations looking to maximize AI’s benefits while minimizing its negative effects on the workforce will benefit greatly from this comprehensive perspective (Rai et al.2019年)。

Sixth, we did not control for industry-specific factors that may influence workplace stressors and environments. Future studies could benefit from examining how the impact of AI adoption on job stress and burnout varies across different industries.

Seventh, we did not include job satisfaction as a control variable. This variable could influence employees’ stress and burnout levels, potentially affecting the relationship between AI adoption and these outcomes. Future research could incorporate job satisfaction measures to more precisely isolate the specific effects of AI adoption.

Lastly, our study did not account for organizational culture, which can significantly impact employee stress and burnout, as the influence of AI adoption on employee outcomes may vary depending on the organizational context. Future studies could explore how different organizational cultures moderate the relationships examined in our research.

As this paper emphasizes the mediating function of work stress and the moderating function of self-efficacy in AI learning, we conclude that AI adoption positively affects employee well-being. Nevertheless, additional research is needed to improve the current understanding of the complex relationships between AI adoption, job stress, and burnout in various settings. Such research should employ multi-method approaches and take into account a wide array of individual and organizational characteristics. Future research can fill these gaps left by the present study and expand upon the current findings to create evidence-based methods to support employees’ health and resilience in the face of rapid technology advancements.

结论

The rapid advancement and widespread deployment of AI technologies across enterprises have changed work dynamics and employee experiences. It is critical to investigate the effects of this technological change on workers’ mental health as AI keeps changing how people perform their jobs. To elucidate the processes and boundary conditions impacting employee outcomes in the AI era, the current paper investigated the complex interplay between different variables.

This study revealed complicated paths by which the adoption of AI affects employee burnout using a thorough three-wave time-lagged design. The results challenge the notion that the use of AI is directly related to burnout, instead highlighting the critical mediation function of job stress. Adapting to new tools, confusion about job tasks, and a larger workload are some of the additional job demands that employees may face as firms incorporate AI technologies. AI pressures can drain workers’ emotional and mental reserves, leading to increased work stress and burnout.

In addition, the study shows that self-efficacy in AI learning significantly moderates the association between AI adoption and job stress. An employee’s stress level caused by the negative effects of AI adoption will be lessened if they have faith in their ability to become an expert in AI. This discovery highlights the significance of empowering employees through focused training and development programs so they can thrive in the face of technological change.

Organizations undergoing AI transformation can greatly benefit from the present study’s findings. Most importantly, organizations must understand that there is more to successful AI adoption than simply implementing technology. Human factors, especially the mental health and resiliency of workers interacting with AI systems, must also be carefully considered. Organizations may create more positive and productive work environments for their employees by anticipating and mitigating any harmful impacts of AI adoption on stress and burnout on the job.

In addition, this study highlights the need for self-efficacy in AI learning to mitigate the harm that AI adoption could do to employees’ well-being. Companies should invest in comprehensive training and development programs that teach workers the technical skills they require and help them feel confident in their ability to master AI. Organizations can foster a workforce that can manage AI adoption by providing workers with the knowledge and skills they need to make good use of AI technologies.

This study also contributes to the growing literature on the mental health effects of AI at work. This study integrated the JD-R model with SCT to better comprehend the complex associations between AI adoption, job stress, self-efficacy in AI learning, and burnout. This study lays the groundwork for future studies to examine other factors that may impact these relationships in different cultural and organizational contexts. It also highlights the importance of the mediating and moderating mechanisms that impact employee experiences concerning AI adoption.

数据可用性

当前研究期间生成和分析的数据集可根据合理要求从相应作者处获得。

参考

Alarcon GM (2011) A meta-analysis of burnout with job demands, resources, and attitudes. J Vocat Behav 79(2):549–562

Anderson JC、Gerbing DW (1988) 实践中的结构方程建模:回顾和推荐的两步方法。Psychol Bull 103(3):411–423

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2007) The Job Demands-Resources model: state of the art. J Manag Psychol 22(3):309–328

Bakker AB, Demerouti E (2017) Job demands-resources theory: taking stock and looking forward. J Occup Health Psychol 22(3):273–285

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Euwema MC (2006) An organizational and social psychological perspective on burnout and work engagement. In: Hewstone M, HAW Schut, De Wit JBF, Van Den Bos K, Stroebe MS (eds) The scope of social psychology: theory and applications. Psychology Press, pp. 229–252

Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Sanz-Vergel AI (2014) Burnout and work engagement: the JD–R approach. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 1(1):389–411

Bandura A (1977) 自我效能:走向行为改变的统一理论。Psychol Rev 84(2):191–215

Bandura A (1986) Social foundations of thought and action: a social cognitive theory.普伦蒂斯霍尔

Bandura A (1997). Self-efficacy: the exercise of control. W. H. Freeman

Bandura A (2012) On the functional properties of perceived self-efficacy revisited. J Manag 38(1):9–44

MathSciNet一个 谷歌学术一个

Bankins S, Ocampo AC, Marrone M, Restubog SLD, Woo SE (2024) A multilevel review of artificial intelligence in organizations: Implications for organizational behavior research and practice. J Organ Behav 45(2):159–182

Barclay D, Higgins C, Thompson R(1995) The partial least squares (PLS) approach to casual modeling: personal computer adoption and use as an illustration Technol Stud 2:285–309

谷歌学术一个

Baxter G, Sommerville I (2011) Socio-technical systems: from design methods to systems engineering. Interact Comput 23(1):4–17

Berente N, Gu B, Recker J, Santhanam R (2021) Managing artificial intelligence. MIS Q 45(3):1433–1450

谷歌学术一个

Borle P, Reichel K, Niebuhr F, Voelter-Mahlknecht S (2021) How are techno-stressors associated with mental health and work outcomes? A systematic review of occupational exposure to information and communication technologies within the technostress model. Int J Environ Res Public Health 18(16):8673

Brace N, Kemp R, Snelgar R (2003) A guide to data analysis using SPSS for windows. Palgrave Macmillan, New York

Brock JKU, von Wangenheim F (2019) Demystifying AI: what digital transformation leaders can teach you about realistic artificial intelligence. Calif Manag Rev 61(4):110–134

Brougham D, Haar J (2018) Smart technology, artificial intelligence, robotics, and algorithms (STARA): employees’ perceptions of our future workplace. J Manag Organ 24(2):239–257

Brynjolfsson E, McAfee A (2017) The business of artificial intelligence. Harv Bus Rev 7:1–20

谷歌学术一个

Budhwar P, Malik A, De Silva MT, Thevisuthan P (2022) Artificial intelligence–challenges and opportunities for international HRM: a review and research agenda. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33(6):1065–1097

Candrian C, Scherer A (2022) Rise of the machines: delegating decisions to autonomous AI. Comput Hum Behav 134:107308

Chae H, Park J, Choi JN (2019) Two facets of conscientiousness and the knowledge sharing dilemmas in the workplace: contrasting moderating functions of supervisor support and coworker support. J Organ Behav 40(4):387–399

Charness N, Boot WR (2016) Technology, gaming, and social networking. In: Schaie KW, Willis SL (eds) Handbook of the psychology of aging. Academic Press, pp. 389–407

Chen Y, Hu Y, Zhou S, Yang S (2023) Investigating the determinants of performance of artificial intelligence adoption in hospitality industry during COVID-19. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 35(8):2868–2889

Cheng B, Lin H, Kong Y (2023) Challenge or hindrance? How and when organizational artificial intelligence adoption influences employee job crafting. J Bus Res 164:113987

Davenport TH, Ronanki R (2018) Artificial intelligence for the real world. Harv Bus Rev 96(1):108–116

谷歌学术一个

De Vos A, Van der Heijden BIJM, Akkermans J (2021) Sustainable careers: towards a conceptual model. J Vocat Behav 117:103196

DeJoy DM, Wilson MG, Vandenberg RJ, McGrathâ€Higgins AL, Griffinâ€Blake CS (2010) Assessing the impact of healthy work organization intervention. J Occup Organ Psychol 83(1):139–165

Demerouti E, Bakker AB, Nachreiner F, Schaufeli WB (2001) The job demands-resources model of burnout. J Appl Psychol 86(3):499–512

Ding L (2021) Employees’ challenge-hindrance appraisals toward STARA awareness and competitive productivity: a micro-level case. Int J Contemp Hosp Manag 33(9):2950–2969

Ding W, Levine R, Lin C, Xie W (2021) Corporate immunity to the COVID-19 pandemic. J Financ Econ 141(2):802–830

Duggan J, Sherman U, Carbery R, McDonnell A (2022) Boundary less careers and algorithmic constraints in the gig economy. Int Natl J Hum Resour Manag 33(22):4468–449

Dwivedi YK, Hughes L, Ismagilova E, Aarts G, Coombs C, Crick T, Williams MD (2021) Artificial Intelligence (AI): multidisciplinary perspectives on emerging challenges, opportunities, and agenda for research, practice and policy. Int J Inf Manag 57:101994

Dwivedi YK, Rana NP, Jeyaraj A, Clement M, Williams MD (2019) Re-examining the unified theory ofacceptance and use of technology (UTAUT): Towards a revised theoretical model. Inf Syst Front 21:719–734

Edwards JR, Caplan RD, Harrison RV (1998) Person-environment fit theory: conceptual foundations, empirical evidence, and directions for future research. In: CL Cooper CL (ed) Theories of organizational stress. Oxford University Press, pp. 28–67

Egana-del Sol P, Bustelo M, Ripani L, Soler N, Viollaz M (2022) Automation in Latin America: are women at higher risk of losing their jobs? Technol Forecast Soc Change 175:121333

Fossen FM, Sorgner A (2022) New digital technologies and hetero geneous wage and employment dynamics in the United States: evidence from individual-level data. Technol Forecast Soc Change 175:121381

Ganster DC, Rosen CC (2013) Work stress and employee health: A multidisciplinary review. J. Manag 39(5):1085–1122

谷歌学术一个

Glavin P, Bierman A, Schieman S (2021) Über-alienated: powerless and alone in the gig economy. Work Occup 48(4):399–431

Glikson E, Woolley AW (2020) Human trust in artificial intelligence: review of empirical research. Acad Manag Ann 14(2):627–660

Goh J, Pfeffer J, Zenios SA (2015) The relationship between workplace stressors and mortality and health costs in the United States. Manag Sci 62(2):608–628

Guthier C, Dormann C, Voelkle MC (2020) Reciprocal effects between job stressors and burnout: a continuous time meta-analysis of longitudinal studies. Psychol Bull 146(12):1146

Hassard J, Teoh KR, Visockaite G, Dewe P, Cox T (2018) The cost of work-related stress to society: Asystematic review. J Occup Health Psychol 23(1):1

Häusser JA, Mojzisch A, Niesel M, Schulz-Hardt S (2010) Ten years on: a review of recent research on the Job Demand-Control (-Support) model and psychological well-being. Work Stress 24(1):1–35

Hobfoll SE (1989) Conservation of resources: a new attempt at conceptualizing stress. Am Psychol 44(3):513–524

Hobfoll SE (2001) The influence of culture, community, and the nested-self in the stress process: advancing conservation of resources theory. Appl Psychol 50(3):337–421

Hobfoll SE, Halbesleben J, Neveu JP, Westman M (2018) Conservation of resources in the organizational context: The reality of resources and their consequences. Annu Rev Organ Psychol Organ Behav 5(1):103–128

Innocenti S, Golin M (2022) Human capital investment and perceived automation risks: evidence from 16 countries. J Econ Behav Organ 195:27–41

Kaplan A, Haenlein M (2020) Rulers of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of artificial intelligence. Bus Horiz 63(1):37–50

Karasek RA (1979) Job demands, job decision latitude, and mental strain: implications for job redesign. Adm Sci Q 24(2):285–308

Karasek R, Theorell T (1990) Healthy work: stress, productivity, and the reconstruction of working life. Basic Books

Keding C, Meissner P (2021) Managerial overreliance on AI augmented decision-making processes: how the use of AI-based advisory systems shapes choice behavior in R&D investment decisions. Technol Forecast Soc Change 171:120970

Khedhaouria A, Cucchi A (2019) Technostress creators, personality traits, and job burnout: a fuzzy-set configurational analysis. J Bus Res 101:349–361

Kim BJ, Kim MJ (2024) The influence of work overload on cybersecurity behavior: a moderated mediation model of psychological contract breach, burnout, and self-efficacy in AI learning such as ChatGPT. Technol Soc 77:102543

Landers RN, Behrend TS (2015) An inconvenient truth: Arbitrary distinctions between organizational, Mechanical Turk, and other convenience samples. Ind Organ Psychol 8(2):142–164

Lazarus RS (1999) Stress and emotion: a new synthesis.施普林格

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1984) Stress, appraisal, and coping.施普林格

Lazarus RS, Folkman S (1987) Transactional theory and research on emotions and coping. Eur J Personal 1(3):141–169

Lee RT, Ashforth BE (1996) A meta-analytic examination of the correlates of the three dimensions of job burnout. J Appl Psychol 81(2):123–133

Leiter MP, Maslach C (2003) Areas of worklife: A structured approach to organizational predictors of job burnout. In: Perrewe PL, Ganster DC (eds) Emotional and physiological processes and positive intervention strategies. Emerald Group Publishing Limited, pp. 91–134

Leiter MP, Maslach C (2016) Latent burnout profiles: a new approach to understanding the burnout experience. Burnout Res 3(4):89–100

Magistretti S, Dell’Era C, Petruzzelli AM (2019) How intelligent is Watson? Enabling digital transformation through artificial intelligence. Bus Horiz 62(6):819–829

Makarius EE, Mukherjee D, Fox JD, Fox AK (2020) Rising with the machines: a sociotechnical framework for bringing artificial intelligence into the organization. J Bus Res 120:262–273

Makridis CA, Han JH (2021) Future of work and employee empowerment and satisfaction: evidence from a decade of technological change. Technol Forecast Soc Change 173:121162

Makridis CA, Mishra S (2022) Artificial intelligence as a service, economic growth, and well-being. J Serv Res 25(4):505–520

Marikyan D, Papagiannidis S, Rana OF, Ranjan R, Morgan G (2022) Alexa, let’s talk about my productivityâ€: the impact of digital assistants on work productivity. J Bus Res 142:572–584

Maslach C, Leiter MP (2016) Understanding the burnout experience: recent research and its implications for psychiatry. World Psychiatry 15(2):103–111

Maslach C, Jackson SE, Leiter MP (1997) Maslach burnout inventory. Scarecrow Education

Maslach C, Schaufeli WB, Leiter MP (2001) Job burnout. Annu Rev Psychol 52(1):397–422

Melamed S, Shirom A, Toker S, Berliner S, Shapira I (2006) Burnout and risk of cardiovascular disease: evidence, possible causal paths, and promising research directions. Psychol Bull 132(3):327–353

Meyer SC, Hünefeld L (2018) Challenging cognitive demands at work, related working conditions, and employee well-being. Int J Environ Res Public Health 15(12):2911

Motowidlo SJ, Packard JS, Manning MR (1986) Occupational stress: its causes and consequences for job performance. J Appl Psychol 71(4):618

Nam T (2019) Technology usage, expected job sustainability, and perceived job insecurity. Technol Forecast Soc Change 138:155–165

Nisafani AS, Kiely G, Mahony C (2020) Workers’ technostress: a review of its causes, strains, inhibitors, and impacts. J Decis Syst 29(sup1):243–258

Oksanen A, Oksa R, Celuch M, Cvetkovic A, Savolainen I (2022) COVID-19 anxiety and wellbeing at work in Finland during 2020–2022: A 5-wave longitudinal survey study. Int J Environ Res Public Health 20(1):680

Pan W, Xie T, Wang Z, Ma L (2022) Digital economy: An innovation driver for total factor productivity. J Bus Res 139:303–311

Peng X, Lee S, Lu Z (2020) Employees’ perceived job performance, organizational identification, and pro-environmental behaviors in the hotel industry. Int J Hosp Manag 90:102632

Pereira V, Hadjielias E, Christofi M, Vrontis D (2023) A systematic literature review on the impact of artificial intelligence on workplace outcomes: a multi-process perspective. Hum Resour Manag Rev 33(1):100857

谷歌学术一个

Pethig F, Kroenung J (2022) Biased humans, (un)biased algorithms? J Bus Ethics 183:637–652

Pillai R, Sivathanu B (2020) Adoption of artificial intelligence (AI) for talent acquisition in IT/ITeS organizations. Benchmarking: Int J 27(9):2599–2629

Podsakoff PM, MacKenzie SB, Lee J-Y, Podsakoff NP (2003) Common method biases in behavioral research: a critical review of the literature and recommended remedies. J Appl Psychol 88(5):879–903

Rai A, Constantinides P, Sarker S (2019) Editor’s comments: next-generation digital platforms: toward human–AI hybrids. MIS Q 43(1):iii–ix

谷歌学术一个

Ryan RM, Deci EL (2000) Self-determination theory and the facilitation of intrinsic motivation, social development, and well-being. Am Psychol 55(1):68–78

Salvagioni DAJ, Melanda FN, Mesas AE, González AD, Gabani FL, Andrade SMD (2017) Physical, psychological and occupational consequences of job burnout: a systematic review of prospective studies. PloS ONE 12(10):e0185781

Shirom A, Melamed S (2006) A comparison of the construct validity of two burnout measures in two groups of professionals. Int J Stress Manag 13(2):176–200

Shrestha YR, Krishna V, von Krogh G (2021) Augmenting organizational decision-making with deep learning algorithms: principles, promises, and challenges. J Bus Res 123:588–603

Shrout PE, Bolger N (2002) Mediation in experimental and nonexperimental studies: new procedures and recommendations. Psychol Methods 7(4):422–445

Sowa K, Przegalinska A, Ciechanowski L (2021) Cobots in knowledge work: human–AI collaboration in managerial professions. J Bus Res 125:135–142

Tarafdar M, Cooper CL, Stich JF (2019) The technostress trifecta-techno eustress, techno distress and design: theoretical directions and an agenda for research. Inf Syst J 29(1):6–42

Tarafdar M, Tu Q, Ragu-Nathan BS, Ragu-Nathan TS (2007) The impact of technostress on role stress and productivity. J Manag Inf Syst 24(1):301–328

Tarafdar M, Tu Q, Ragu-Nathan TS, Ragu-Nathan BS (2011) Crossing to the dark side: examiningcreators, outcomes, and inhibitors of technostress. Commun ACM 54(9):113–120

Taris TW (2006) Is there a relationship between burnout and objective performance? A critical review of 16 studies. Work Stress 20(4):316–334

Tong S, Jia N, Luo X, Fang Z (2021) The Janus face of artificial intelligence feedback: deployment versus disclosure effects on employee performance. Strateg Manag J 42(9):1600–1631

Trist EL, Bamforth KW (1951) Some social and psychological consequences of the longwall method of coal-getting: An examination of the psychological situation and defences of a work group in relation to the social structure and technological content of the work system. Hum Relat 4(1):3–38

Uren V, Edwards JS (2023) Technology readiness and the organizational journey towards AI adoption: an empirical study. Int J Inf Manag 68:102588

Van der Heijden B, Brown Mahoney C, Xu Y (2019) Impact of job demands and resources on nurses’ burnout and occupational turnover intention towards an age-moderated mediation model for the nursing profession. Int J Environ Res Public Health 16(11):2011

Vrontis D, Christofi M, Pereira V, Tarba S, Makrides A, Trichina E (2022) Artificial intelligence, robotics, advanced technologies and human resource management: a systematic review. Int J Hum Resour Manag 33(6):1237–1266

Walkowiak E (2021) Neurodiversity of the workforce and digital transformation: the case of inclusion of autistic workers at the workplace. Technol Forecast Soc Change 168:120739

Wood AJ, Graham M, Lehdonvirta V, Hjorth I (2019) Good gig, bad gig: autonomy and algorithmic control in the global gig economy. Work, Employ Soc 33(1):56–75

Wu TJ, Li JM, Wu YJ (2022) Employees’ job insecurity perception and unsafe behaviours in human–machine collaboration. Manag Decis 60(9):2409–2432

Xanthopoulou D, Bakker AB, Demerouti E, Schaufeli WB (2007) The role of personal resources in the job demands-resources model. Int J Stress Manag 14(2):121–141.https://doi.org/10.1037/1072-5245.14.2.121

Zirar A, Ali SI, Islam N (2023) Worker and workplace Artificial Intelligence (AI) coexistence: emerging themes and research agenda. Technovation 124:102747

致谢

This study was supported by the BK21 FOUR program (Education and Research Center for Securing Cyber-Physical Space) through the National Research Foundation (NRF) funded by the Ministry of Education of Korea (5199990314137).

道德声明

利益竞争

作者声明没有竞争利益。

道德认可

The survey conducted in this study adhered to the standards outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. The Yonsei University Institutional Review Board granted ethical approval. Approval number: 202208-HR-2975-01. Date of approval: 15.08.2022, Scope of approval: All research variables in this study.

知情同意

已获得知情同意。Every participant was provided with information about the objective and extent of this study, as well as the intended utilization of the data.The respondents willingly and freely participated in the study.Their identities were kept confidential, and their involvement was optional.Prior to participating in the survey, all subjects included in the study provided informed consent.Informed consent was obtained from March 2022 to April 2022 through the website of the research company (Macromil Embrain).The scope of the consent covered participation, data use, and consent to publish.Online explanatory statement and documents related to exemption from written consent.Since the explanatory statement requires consent three times, it was submitted on the first, second, and third questionnaires.By default, written consent was waived.The reason for this is as follows.This survey was conducted through Macromil Embrain, a research company that has the largest panel in Korea (25 years of experience in the industry).Individuals belonging to the panel of Macromil Embrain registered in the company’s survey response system and agreed to provide their information and survey content.Then, they logged in to the system and responded to the survey.At this time, the research company announced the contents of the researcher’s survey, and panels interested in the survey participated in the survey.Alternatively, the research company asked those who were qualified to participate in the survey (e.g., office workers at a domestic company) via e-mail or text message about their intention to participate in the survey.This process was conducted entirely online, and it was practically impossible to obtain the consent of the research subjects because the researcher did not know which panel would respond to the questionnaire.Sufficient voluntary participation in research was ensured, and explanations regarding the guarantee of withdrawal and suspension of participation were supervised by the aforementioned research company.A research company manages this company’s website by asking for consent when an individual signs up and registers.When a person signs up for this company’s service as a panel, these matters are explained in detail, and consent is obtained.Only those who gave their consent participated in the survey.The condition for selecting study subjects was that they must have been adult employees working for domestic companies.If participants were adult employees working for a domestic company, there were no special conditions such as regular or non-regular workers.People excluded from the study were those who were not currently working or who did not have the intellectual ability to understand and respond appropriately to the questionnaire.Also, people with limited ability to give consent for research or those who were vulnerable were not included as research subjects.Only those panels who had voluntarily registered to participate in the survey with the research company (Macromil Embrain) took part in the survey.In particular, when issuing a recruitment notice, the general subject and risks of the study were noted, and personal privacy was ensured during recruitment.Steps were taken to ensure the protection and confidentiality of participants.We did not include vulnerable research subjects.Vulnerability could be judged voluntarily by survey respondents.In addition, only those who met the research company’s criteria (mentioned above) could participate in the survey.The process and contents of the second and third surveys were the same as in the first survey.

附加信息

出版商备注施普林格·自然对于已出版的地图和机构隶属关系中的管辖权主张保持中立。

权利和权限

开放获取本文获得 Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License 的许可,该许可允许以任何媒介或格式进行任何非商业使用、共享、分发和复制,只要您给予原作者适当的署名即可和来源,提供知识共享许可的链接,并指出您是否修改了许可材料。根据本许可,您无权共享源自本文或其部分内容的改编材料。本文中的图像或其他第三方材料包含在文章的知识共享许可中,除非材料的出处中另有说明。如果文章的知识共享许可中未包含材料,并且您的预期用途不受法律法规允许或超出了允许的用途,则您需要直接获得版权所有者的许可。要查看此许可证的副本,请访问http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/。转载和许可

引用这篇文章

Kim, BJ., Lee, J. The mental health implications of artificial intelligence adoption: the crucial role of self-efficacy.

Humanit Soc Sci Commun11 , 1561 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04018-w下载引文

:2024 年 7 月 9 日

:2024 年 10 月 28 日

:2024 年 11 月 17 日

:https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04018-whttps://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-024-04018-w