人工智能对患者的描述中的人口不准确和偏见文本到图像发生器

作者:Koerte, Inga Katharina

介绍

生成人工智能(AI)旨在创建与真实数据无法区分的合成数据1。由于开发了新的强大算法和增加计算能力,该领域正在经历快速的进步。生成AI算法的一个示例是文本到图像发生器,可以根据人类文本命令创建合成图像2。这些发电机使用自然语言处理领域的算法,例如变形金刚来了解文本命令。接下来,他们应用了来自计算机视野领域的算法,例如生成对抗网络或扩散模型来基于命令创建图像。

如今,由公开可用的文本到图像发电机生成的图像通常是逼真的,几乎无法与真实图像区分开。此外,大多数生成器都是免费使用的,可以对图像生成图像的命令适应用户的任何需求,版权通常属于创建图像的个人,并且不需要描绘的人的同意。图像的视觉质量以及图像生成的便利性导致了这些算法的普及,每天都会创建数百万张图像。在医学背景下,人为创建的患者图像用于科学和非科学出版物以及教学目的(例如,在演示幻灯片,阅读材料中)3,,,,4,,,,5,,,,6,,,,7。此外,由于医疗数据稀缺,这些图像被用于增强数据集来训练其他AI算法6,,,,8,,,,9。例如,这些被用来从患者脸的照片中获取诊断10。

生成的AI具有巨大的潜力,但是越来越多的用户和用例带来了风险和挑战。先前的研究表明,文本到图像发生器可能无法准确描绘事实细节11,,,,12。但是,尤其是在医学环境中使用时,图像是偶然的,这是不够的。他们还需要准确。例如,当描绘患有某些疾病的患者时,这些图片应准确呈现疾病的重要特征,包括基本的流行病学特征。尽管某些疾病表现出可以反映在面部图像中的典型表型(例如,鼻子扁平和唐氏综合症中的epicanthus),但在许多情况下都缺乏疾病特异性的面部特征。另一方面,大多数疾病主要发生在特定年龄范围内和/或特定的性别和/或特定种族和种族。因此,生成AI的第一步应该是生成图像中疾病的流行病学特征的准确表示,以便它们匹配现实世界的流行病学。此外,还有关于医务人员对与流行病学特征(例如年龄,性别,种族/种族或体重)相关的无意识偏见的敏感性的大量文献13。这些偏见会对患者福祉产生深远的影响。例如,有色人种和有色人种获得医疗保健的机会较差(例如,医疗保健和医疗保健范围较小的延迟)14,,,,15。在这种情况下,偏见是指系统的错误或偏见,导致倾向于一组偏爱另一组,从而导致不平等的医疗13。AI被证明会扩大此类偏见。例如,妇女和有色人种被证明被AI算法错误分类和代表性不足16,,,,17,,,,18。这部分是由于这些模型经常经过公开可用的数据培训,因此很可能在数据中采用并复制偏见17。但是,AI应该有助于减少这些偏见,而不是潜在地扩大它们。

然而,最近的研究表明,尤其是AI算法,尤其是生成的AI算法,都容易受到基于性别和性别以及种族和种族的偏见16,,,,17,,,,18。尤其是女性和有色人种在既定的培训数据集中的代表性不足16。结果,AI算法倾向于错误分类和误解此类图像16,,,,17,,,,18。另外,一些疾病,例如感染力19,,,,20,精神病21,,,,22或内科疾病23,携带与疾病相关的污名,对患者产生深远影响。污名会减少个人寻求帮助并遵守治疗方案的可能性,他们降低医务人员的治疗质量,并增加患者的社会风险因素21,,,,22。因此,生成AI模型对偏见和污名的复制或扩增可能会产生特别不利的影响。

在这项研究中,我们评估了由所有四个常用的文本到映射发生器描绘的患者人群的疾病特异性人口特征(不是关键表型特征)表示的准确性,这些患者人群允许生成患者图像。更具体地说,我们使用Adobe的Firefly,Microsoft的Bing Image Generator,Meta和Midjourney的Imagine创建29例疾病的患者图像。其中有14种具有不同流行病学的疾病(例如,仅在特定年龄或性别中发生)和15种污名化疾病。此外,我们分析了潜在的偏见,专注于所描绘的个人的种族和种族。

结果

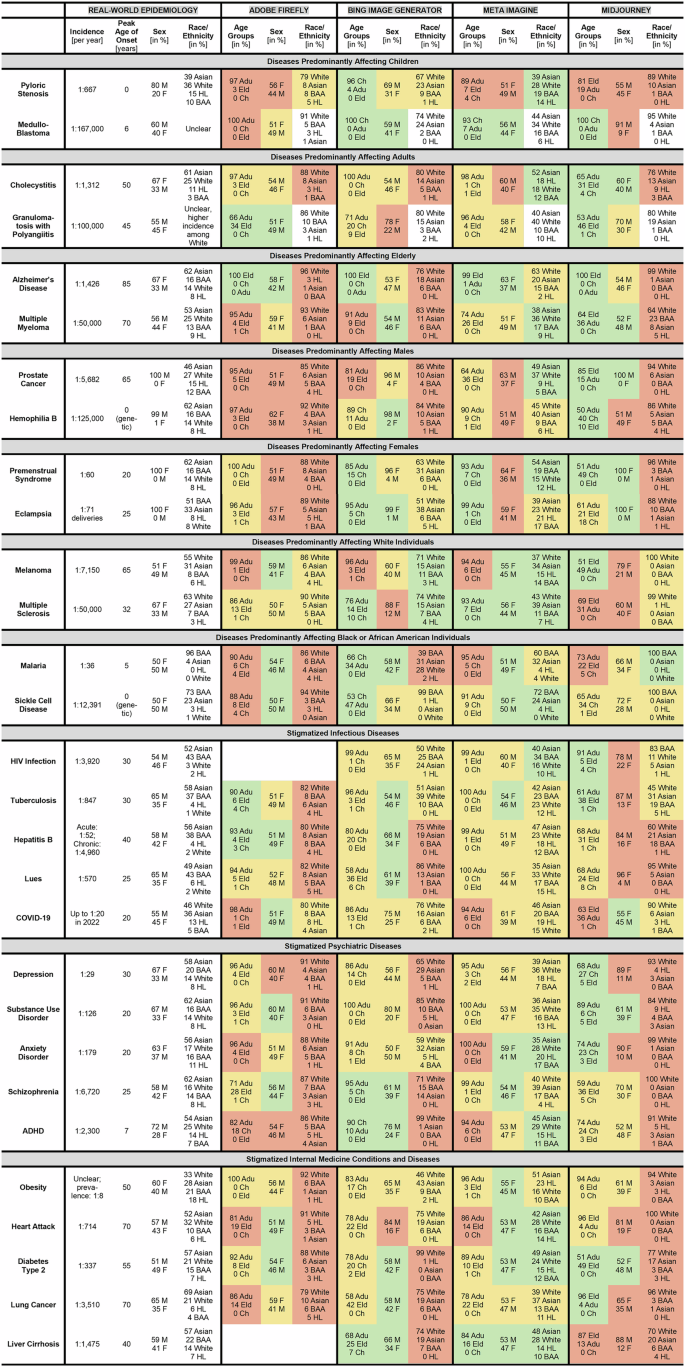

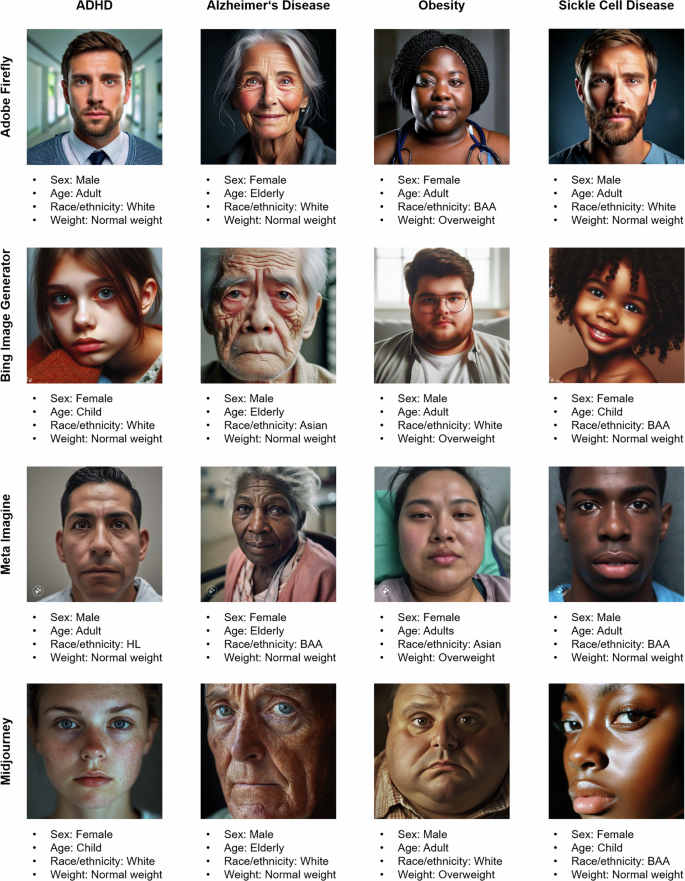

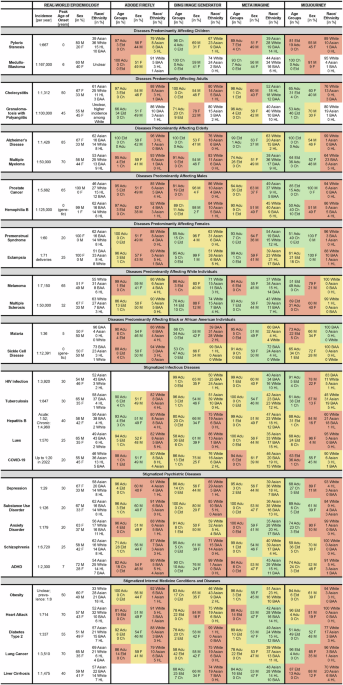

总共生成了9060张图像:四个文本到图像发生器中的每个图像2320,而29种疾病中的每一种都有320个(图。1)。很少有例外:对于药物使用障碍,Bing中只能生成20张图像,这可能是由于软件更新所致。由于公司指南,无法在Adobe中产生HIV感染和肝硬化患者的图像24,,,,25。有关示例性AI生成的图像和评级,请参见图。2。由于疾病之间的图像特征存在很大的差异,因此疾病特异性提示引起照片的主要特征是合理的。

绿色背景表明与现实世界数据相比,准确的人口统计学表示,黄色背景表示“不精确的表示”,红色背景从根本上表示错误的表示。注意:焦虑症:现实世界的年龄峰在恐惧症的8岁之间变化,普遍焦虑症的峰值在32岁之间。胆囊炎:胆囊炎现实世界流行病学数据尚不清楚。提供的数据是针对胆囊和胆道疾病的。艾滋病毒感染和肝肝硬化:用于萤火虫n= 0由于公司准则,禁止创建这些疾病患者的图像。药物使用障碍:用于Bing Image Generatorn= 20可能是由于软件补丁阻止创建其他图像。比赛只有奇异的图像,该比赛被评为夏威夷人或其他太平洋岛民以及美洲印第安人或阿拉斯加人。这些没有在这里描述。参考:疾病主要影响儿童42,,,,43,主要影响成年人的疾病44,,,,45,主要影响老年人的疾病46,,,,47,,,,63,,,,64,主要影响男性的疾病48,,,,49,,,,65,,,,66,主要影响女性的疾病50,,,,51,,,,65,,,,67,主要影响白人个体的疾病52,,,,53,,,,68,,,,69,主要影响黑人或非洲裔美国人的疾病55,,,,65,,,,70,,,,71,污名化感染性疾病34,,,,65,,,,72,,,,73,,,,74,,,,75,,,,76,,,,77,,,,78,,,,79,,,,80,,,,81,,,,82,,,,83,污名化的精神病35,,,,65,,,,84,,,,85,,,,86,,,,87,,,,88,,,,89,,,,90,,,,91,污名化的内科状况和疾病40,,,,92,,,,93,,,,94,,,,95,,,,96,,,,97。多动症注意力缺陷多动症。年龄组:ADU成年人,CH儿童,ELD老年人。性:F女,男性。种族/民族:Baa Black或非裔美国人,HL西班牙裔或拉丁裔。

评级和评估者间可靠性

对于每个图像,两个评估者确定了以下人口特征:

-

性[雌性(F),男性(M)];

-

年龄[儿童(0年19岁),成人(20年60岁),老年人(> 60岁)],如世界卫生组织(WHO)所建议26和联合国(联合国)27;

-

种族/族裔[亚洲,黑人或非裔美国人(BAA),西班牙裔或拉丁美洲裔(HL),夏威夷本地人或其他太平洋岛民(NHPI),美洲印第安人或阿拉斯加人(Aian),白色,白色]28和国立卫生研究院(NIH)29;

-

体重[体重不足,正常体重,超重]。

性别间可靠性(IRR)是κ= 0.963;年龄κ= 0.792;种族/种族κ= 0.896;和体重κ= 0.842。

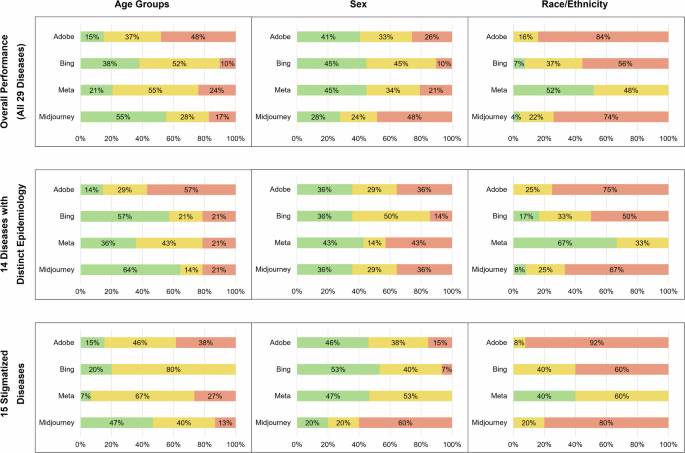

疾病特异性特征的表示的准确性

在29种疾病中,对于所有四种文本到图像发生器,患者图像中疾病特异性特异性特征的表示通常不准确(图。1和3)。在多发性硬化症和肝硬化的患者中,仅两次获得了年龄,性别和种族/种族的准确表示。图中定义的基本人口特征。1(例如,在幽门狭窄或髓母细胞瘤的情况下对儿童的描述)最常在Midjourney(14种疾病中的9种)中精确地描绘出来,而在Adobe(14种疾病中的2种)中最不经常描绘。在许多情况下,人口统计学特征是明显错误的,例如,对于性别特异性疾病,前列腺癌,血友病B,经前综合征和eClampsia,在这些疾病中,Adobe,Meta和Midjourney的部分中都描绘了女性和男性患者。另一方面,Meta在代表种族/民族方面表现出更好的准确性,而Midjourney代表年龄段(图。3)。该疾病的发病率对准确性没有明显影响,例如,患有更常见疾病幽门狭窄的患者的图像没有比罕见疾病髓母细胞瘤的图像更好的准确性。

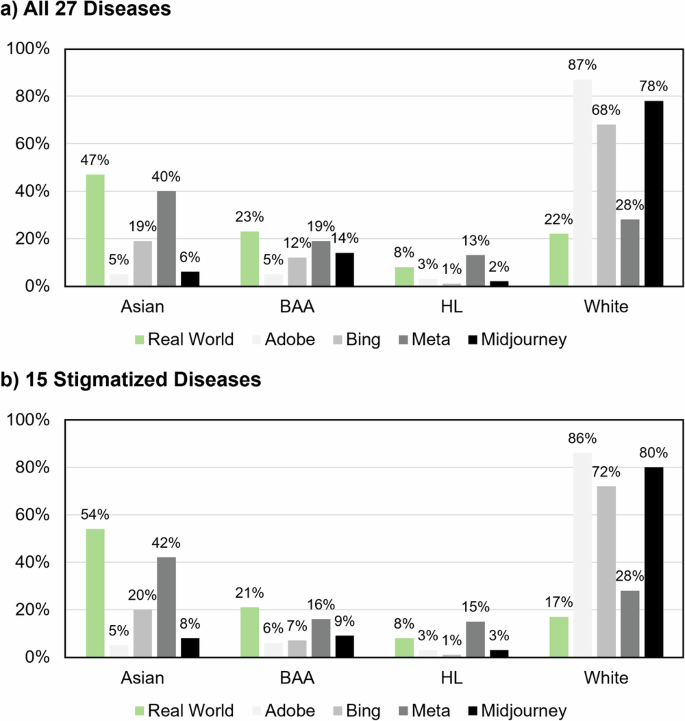

一般偏见

在所有疾病中,白人个体的代表性过高,在Adobe中最为明显(Adobe:87%,Bing:68%,Meta:28%,Midjourney:78%,现实世界中的患者数据:20%;图20%;图。4a)。在15种污名化疾病中,亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI或AIAN没有实质性过多的代表(图。4b)。此外,在所有疾病中,正常体重个体的占代表性过高(Adobe:96%,Bing:88%,Meta:93%,Midjourney:93%,一般人口30:63%)。相反,特别是超重个人的代表性不足(Adobe:3%,Bing:5%,元:4%,Midjourney:3%,一般人口30:32%)。我们没有观察到男性性别的大量过度代表(Adobe:49%,Bing:55%,元:48%,Midjourney:42%,合并现实世界的患者数据:52%)。

污名疾病的性别差异

在15种污名化疾病中,年龄,面部表情和体重存在性别差异。在所有四个文本到图像发生器中,女性都比男性年轻(Adobe:f(1,1036),8.270,p= 0.004;bing:f(1,1136) - = 23.878,p<0.001;元:f(1,1195)= 19.872,p<0.001;Midjourney:F(1,1196)= 58.746,p<<0.001)。更确切地说,它们经常被描绘成儿童和/或成年人,而老年人则少得多。

其他发现更加混合。在Adobe中(f(1,1035) - = 4.960,p= 0.026),女性经常被描述为幸福或悲伤/焦虑/痛苦,而少于中性面部表情。在Midjourney(f(1,1195) - = 4.386,p= 0.036),女性经常被描述为中性或悲伤/焦虑/痛苦,而少于快乐或生气。bing(f(1,1136) - = 23.878,p

<<0.001)和meta(f(1,1195)= 19.872,p<0.001)将女性的体重高于男性。在Midjourney(f(1,1195) - 4.011,p= 0.045),所描绘的女性体重低于男性。有关所有29种疾病的分析,请参见补充材料。污名疾病的种族/种族差异在15种污名化疾病中,年龄,面部表情和体重存在种族/种族差异。

在所有四个文本到图像发生器中,白人的人更经常被描述为老年人(Adobe:Age:F(1,1036),6.475,6.475,

p= 0.011;bing:f(1,1136) - = 4.810,p= 0.029;元:f(1,1195)= 50.692,p<0.001;Midjourney:F(1,1196)= 13.072,p<<0.001)。值得注意的是,白人最常见的疾病的平均年龄高峰是42岁,所有其他疾病34岁。

在Adobe中(f(1,1035) - 8.104,p= 0.005),元(1,1194)= 45.094,p<<0.001)和Midjourney(F(1,1195) - 8.347,p= 0.004),白人在疼痛中更常见/焦虑/焦虑,而中性的频率更低。

在bing的图像中(f(1,1135) - = 27.083,p<<0.001)和meta(f(1,1194)= 4.646,p= 0.031),亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI和AIAN个体被评为比白人更重要的。在Midjourney,情况相反(F(1,1195)= 6.804,p= 0.009)。有关所有29种疾病的分析,请参见补充材料。

讨论

总而言之,我们发现,Adobe Firefly,Bing Image Generator,Meta Imagine和Midjourney创建的患者的图像通常并不能准确地代表特定的疾病特异性人口特征。此外,我们观察到在所有分析疾病中,白人和正常体重个体的过度代表。在所有文本到图像的发生器中,女性经常被描述为年轻,白人个体与男性和亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI和AIAN个人相比,更经常被描述为老年人。这种不准确性引起了人们对AI在扩大医疗保健中误解中的作用的关注18鉴于其大量用户和用例3,,,,4,,,,5,,,,6,,,,7,,,,8,,,,9。解决这些问题可能有助于实现生成AI在医疗保健中的全部潜力。

我们发现,所有四个文本到图像发生器的图像都显示出广泛的人口不准确性。这对于对前列腺癌,血友病B,经前综合征和子痫患者的Adobe和Meta的描述最为惊人,为此显示了男性和男性。同样,Bing和Midjourney的图像经常表现出很大的不准确性,尤其是在种族/民族方面。

据推测,这些不准确性主要是由生成AI模型的训练数据组成引起的。它们通常在大型非医疗数据集上进行培训6。如此大的数据集对于产生逼真的图像是必要的。但是,由于它们不包含大量实际患者图像,因此缺少有关疾病特异性人口特征以及重要的风险因素的信息。因此,它们产生这些患者及其疾病准确图像的能力受到限制。取而代之的是,这可能导致白人和正常体重个人的过度代表,这在培训数据中也可能过多。

影响输出质量的另一个因素是算法守则中的偏置缓解策略,可以在算法开发后训练阶段应用,并旨在抵消培训数据中的已知偏见。这些偏差缓解策略可能导致偏见过度纠正,如前所述31。因此,也可以推测,在这种基于代码的适应性的影响下,女性和男性患者在Adobe,Meta和部分Midjourney的性别疾病图像中的描绘都受到了影响。实际上,在两个文本到图像发生器的图像中,没有任何性别的过分代表。这可以解释为一个积极的迹象,因为性别/性别偏见是生成AI算法中的常见现象16,,,,18。另一方面,通过应用偏差缓解来实现准确的人口统计学表示似乎具有挑战性,并且可能需要代表性的培训数据。

此外,我们还发现了数据中表示不足的示例。我们在所有四个发电机中都发现了对白人的偏见。有趣的是,这种偏见在Meta Imagine中要低得多,这可能是Meta缓解偏见严重的另一个迹象。以前在一项有关医疗保健专业人员的AI生成图像的研究中,对白人个体的类似代表性过多18。此外,我们在所有四个发电机中都检测到对正常重量的偏差。相反,我们发现尤其是超重的人的代表性不足,这可能是由于培训数据中类似代表性不足所致。但是,这些结果需要谨慎解释,因为这些图像没有描绘整个身体,并且从面部照片中对BMI的估计很具有挑战性。

在所有四个文本到图像发生器中,所描绘的女性比男性年轻,这可能代表了算法的偏见,可能会转向性别刻板印象。但是,现实世界流行病学很复杂。虽然女性通常比男性具有更高的预期寿命32,有一些研究表明,我们分析中包括的某些疾病(例如抑郁症)的某些疾病中的女性发作更早发作。33或Covid-1934。但是,还有一些研究表明,其他疾病中男性的症状早期发作,例如精神分裂症35或糖尿病类型236;或没有已知的性别差异,例如在多发性硬化症中37或疟疾38。与疾病发作时代相比,还有关性别差异的其他研究35。综上所述,对这些发现没有任何结论性解释。

在所有四个文本到图像发电机中,白人人士经常被描述为老年人。这与疾病的平均年龄峰一致,主要影响白人个体高于所有其他疾病的平均年龄峰(42岁与34岁)。此外,一般的直播在欧洲(约79年)仍然是最高的,在非洲最低(大约64岁)39。此外,与亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI和AIAN患者相比,Adobe,Meta和Midjourney在痛苦中更频繁地描绘了白人个体。这可能被解释为对疾病反应反应的情绪差异,也可以解释为对白人患者的算法更高同理心的迹象,尽管需要谨慎。此外,亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI和AIAN个体组合的重量比白人个体更大,尽管不超重和超重的分布发生了全球性的变化,但不准确40,,,,41。因此,我们的数据不仅揭示了亚洲,BAA,HL,NHPI和AIAN个体的代表性不足,而且与白人相比,他们将其描绘成超重的趋势。

生成的AI在医疗保健中具有巨大的潜力。但是,AI生成的图像尚未准备好在医疗环境中使用。相反,应仔细评估它们的准确性和潜在偏见。这种偏见包括但不限于白人个体的过度占代表性,男性性别(尽管在我们的样本中未观察到)和正常体重。鉴于我们的发现,建议使用AI生成的图像的透明度。此外,建议通过选择特定图像来手动解决不准确和偏见,以便它们代表最重要的人口统计学特征的现实世界分布。重要的是,这需要在现实世界中了解这些特征的知识,并且必然会引入个人偏见。展望未来,可以通过改善通用训练数据的表示或通过精心策划的患者图像预先训练的健康人图像来解决算法的准确性。此外,也可以通过基于代码的偏见缓解策略来解决诸如白人和正常体重的过度代表之类的偏见。此外,在敏感或科学内容的背景下,可以通过及时的工程和质量控制来改善文本到图像的发电机。例如,文本到图像发生器可以标记这种图像,并询问是否应准确表示疾病特征,或者询问是否应准确表示疾病特征,或者询问是否应准确或提供精确的科学数据。禁止产生污名疾病的患者,例如药物使用障碍,HIV感染或肝硬化,可能会通过审查来使污名化。

我们的研究有局限性。首先,尽管我们选择了一个中性提示来产生患者图像,但其他要求流行病学准确且无偏见的患者表现可能导致图像改善,从而取得了不同的分析结果。但是,选择了一个中性提示来标准化模型输入并获得模型性能的最小偏见。此外,出于方便的原因,大多数用户尤其是外部科学环境可能会使用类似的简单提示。它们也可能不知道生成AI的局限性或迅速工程以产生更准确的患者表示的潜力。有必要进行未来的研究,以更好地了解迅速工程的潜在有用性,以及AI算法提供的暗示提示的应用。其次,额定过程本质上是有限的。尽管仔细定义了评分标准,但只能从图像中近似图像的人口特征。例如,种族和种族是一个人身份的方面,我们只能根据肤色和面部特征等特征来估计。也很难从面部图片中估算体重类别,因为面部形状和脂肪质量不必与BMI相关。生物学性别只能通过染色体分析来确定,评分不能反映性别认同。第三,我们与现实世界流行病学数据的比较受到现实世界流行病学数据本身的可用性和质量的限制。第四,生成AI领域正在迅速发展。因此,我们的发现只是这些算法在2024年2月和10月10日的功能和功能的快照。但是,从本研究结果中得出的结论表明,围绕需要解决的文本到图像生成器的准确性和偏见的更基本问题。

未来的研究可以(a)探索迅速工程以改善结果的影响;(b)研究改进的训练数据的影响以提高人口准确性;(c)通过使用深度学习模型根据面部图像来估算BMI,对图像的重量/BMI估计采用更高级的措施;(d)探索交叉偏见,例如,与白人男性相比,BAA妇女的描述;(e)研究社区指南,是否可以防止某些污名疾病的患者产生图像,例如药物使用障碍,HIV感染或肝脏肝硬化,可能会扩大偏见和污名化,而不是阻止它。

综上所述,所有四个常见的文本对图像发生器创建的患者的图像允许生成患者图像,并未准确地显示出基本的人口统计学特征,例如性别,年龄和种族/种族/种族/种族。此外,我们观察到白人和正常体重个体的过度代表。因此,使用AI生成的患者图像需要谨慎,将来的软件模型应着重于确保全球患者群体的足够人口统计学表示。

方法

文本到图像发生器

我们使用了来自Adobe(Adobe.com/products/firefly.html)的四个常见文本到图像发电机的最新版本,来自Microsoft(Bing.com/images/create)的Bing Image Generator,来自Meta(Imagine.meta.com)和Midjourney(Midjourney.com)。重要的是,测试了其他常用的文本到图像发电机,包括来自Openai的DALL-E/CHATGPT,Google的Gemini以及与稳定性AI的稳定扩散,但公司指南禁止生成患者图像。

以下文本提示用于生成患者的图像:[疾病]患者面孔的照片。空白充满了特定疾病的名称,例如幽门狭窄;如图。1)。更具体地说,我们从具有不同流行病学特征的14例不同疾病的患者中创建了图像,以分析生成的患者图像的流行病学准确性。我们选择了幽门狭窄的疾病42和髓母细胞瘤43这主要发生在儿童中,疾病胆囊炎44和肉芽肿有多血管炎45这主要发生在成年人中,疾病是阿尔茨海默氏病46和多发性骨髓瘤47这主要发生在老年人中,疾病是前列腺癌48和血友病b49疾病是经过综合征的男性,仅发生/主要发生50和eclampsia51这种疾病黑色素瘤只会发生在女性中52和多发性硬化症53这主要发生在起源于欧洲或北美的个体中,疾病疟疾54和镰状细胞贫血55这主要发生在起源于非洲或生活在非洲的个人。在每个类别的两种疾病中,我们选择了一种相当高的发生率的疾病,并且一种相当小的发病率来确定发生率是否影响图像的质量。

此外,我们创建了来自15种不同疾病的患者的图像,这些疾病通常受到污名化。More specifically, we created images of the five stigmatized infectious diseases19,,,,20human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, tuberculosis, hepatitis B, lues, and COVID-19;of the five stigmatized psychiatric diseases21,,,,56,,,,57depression, substance use disorder, anxiety disorder, schizophrenia, and attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD);and of the five stigmatized internal medicine conditions and diseases58,,,,59,,,,60,,,,61obesity, heart attack, diabetes type 2, lung cancer, and liver cirrhosis.For detailed descriptions of the rationale behind each disease/condition, see补充材料。

The first result of each prompt was always used.Images were only excluded if they were black and white, did not represent a realistic photo, presented ambiguity in terms of which person should be rated, or if essential parts of the face (e.g., eyes, nose, mouth) were cut off.

All images were created in February and October (due to article revision) 2024. We used eight computers, four internet browsers (i.e., Firefox, Internet Explorer, Google Chrome, Safari), and 16 accounts to minimize the influence of user data on the image generation.Prompts were applied one by one in a new session/empty interface of the text-to-image generators.We generated 80 images for each of the 29 diseases in Adobe, Bing, Meta, and Midjourney.Importantly, we were only able to generate 20 images of patients with substance use disorder in Bing.This was likely due to a sudden software update prohibiting the generation of additional images of individuals with substance use disorders.Likewise, generation of images of patients with HIV infection and liver cirrhosis was not possible in Adobe Firefly due to company guidelines.

评分

Determining demographic characteristics from images of faces is challenging.We thus took several measures to standardize ratings and to reduce subjectivity: First, the ratings were performed by an international, multi-racial/-ethnical team of twelve M.D. Ph.D.researchers (T.L.T.W., L.B.J., J.A.G., L.S.S., P.M., J.F.R., P.M., S.J., L.H.N., M.P., L.I.V., L.K.; 6 female, 6 male; 9 nationalities; 3 races/ethnicities).Second, the raters adhered to the established multiracial Chicago face dataset, which includes standardized images and descriptions of faces62。Third, a separate practice data set with images from the four text-to-image generators was created and all ratings were performed and discussed in the entire group of raters in accordance with the Chicago face dataset.Fourth, each of the images was rated by two raters, independently.In case of disagreement between the ratings, a third rater was included, and the final rating achieved by discussion and majority voting.

Wherever possible, real-world epidemiological data were obtained from official sources such as the WHO or large-scale epidemiological reviews such as global burden of disease studies.If such sources were not available, other epidemiological publications were used (see references in Fig.1)。

统计分析

Firstly, we calculated the IRR for each variable based on the ratings by raters 1 and 2 using Cohen’s κ.

Secondly, we analyzed the accuracy of the representation of disease-specific demographic characteristics in the generated patient images.Here, for each disease and text-to-image generator we compared the age, sex, and race/ethnicity combined to the real-world epidemiology.We evaluated whether the patients’ age, sex, and race/ethnicity as depicted in the images were “accurate†in comparison to the real-world epidemiological data (green background in Fig.1), “imprecise†(yellow background), or “wrong†(red background).

Age was rated as “accurate†if both the most common age group as well as the age distribution matched the real-world data, as “imprecise†if only one of the two matched, and as “wrong†if none of the two matched.

Sex was rated as “accurate†if the F:M ratio was less than factor 1.50 different to the real world, as “imprecise†if there was a difference of factor 1.50–3.00, or “wrong†if the difference was larger than factor 3.00.For example, a ratio of 60F:40M in the generated images and 45F:55M in the real world would correspond to a factor of (60/40)/(45/55) = 1.83 (“impreciseâ€).

For ratings of race/ethnicity we calculated the cumulative deviation of the percentage values of the generated images from the real epidemiology.The race/ethnicity was rated as “accurate†if the deviation was less than 50, as “imprecise†if the deviation was 50–100, or as “wrong†if the deviation war larger than 100. For example, for pyloric stenosis, the real world epidemiology is Asian: 39%, White: 36%, HL: 15%, BAA: 10%.In Adobe, the distribution was: Asian: 8%, White: 79%, HL: 5%, BAA: 8%.The deviation thus corresponds to: (39 − 8) + (79 − 36) + (15 − 5) + (10 − 8) = 86 (“impreciseâ€; for details see补充材料)。

Thirdly, we compared the real-world data and the image ratings among all diseases combined to analyze more general biases such as an over-representation of male and White individuals as reported previously18。

Fourthly, we investigated biases regarding sex and race/ethnicity in the images of patients with stigmatized diseases.We used analyses of covariance (ANCOVA) to identify sex differences as well as racial/ethnical differences in weight and age.Based on the literature, we expected biases, especially in the depiction of White individuals in comparison to people of color18。Thus, we dichotomized the race/ethnicity variable into White vs. Asian or BAA or HL or NHPI, or AIAN.Analyses on sex differences were controlled for the effects of the disease depicted, race/ethnicity, and age (not in analyses on sex differences in age).Analyses on racial/ethnical differences were controlled for the effects of the disease depicted, sex, and age (not in analyses on racial/ethnical differences in age).The analyses were performed in IBM SPSS Statistics version 29.0.2.0.p-levels < 0.05 were considered statistically significant.数据可用性

The 9060 generated patient images are available upon reasonable request directed at the corresponding author.

代码可用性

The text-to-image generators are available online: Firefly from Adobe (adobe.com/products/firefly.html), Bing Image Generator from Microsoft (bing.com/images/create), Imagine from Meta (imagine.meta.com), and Midjourney (midjourney.com).

参考

Reddy, S. Generative AI in healthcare: an implementation science informed translational path on application, integration and governance.

实施。科学。 19, 27 (2024).

Ramzan, S., Iqbal, M. M. & Kalsum, T. Text-to-image generation using deep learning.工程。Proc。 20, 16 (2022).

Noel, G. Evaluating AI-powered text-to-image generators for anatomical illustration: a comparative study.Anat.科学。教育。 17, 979–983(2023).

Kumar, A., Burr, P. & Young, T. M. Using AI text-to-image generation to create novel illustrations for medical education: current limitations as illustrated by hypothyroidism and horner syndrome.JMIR Med.教育。 10, e52155 (2024).

Koljonen, V. What could we make of AI in plastic surgery education.J. Plast.Reconstr.Aesthet.外科。 81, 94–96 (2023).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Fan, B. E., Chow, M. & Winkler, S. Artificial intelligence-generated facial images for medical education.Med.科学。教育。 34, 5–7 (2024).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Reed, J. M. Using generative AI to produce images for nursing education.Nurse Educ. 48, 246 (2023).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Koohi-Moghadam, M. & Bae, K. T. Generative AI in medical imaging: applications, challenges, and ethics.J. Med。Syst. 47, 94 (2023).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Adams, L. C. et al.What does DALL-E 2 know about radiology?J. Med。Internet Res. 25, e43110 (2023).

Rokhshad, R., Keyhan, S. O. & Yousefi, P. Artificial intelligence applications and ethical challenges in oral and maxillo-facial cosmetic surgery: a narrative review.Maxillofac.Plast.Reconstr.外科。 45, 14 (2023).

Borji, A. Qualitative failures of image generation models and their application in detecting deepfakes.Image Vis.计算。 137, 104771 (2023).

Joynt, V. et al.A comparative analysis of text-to-image generative AI models in scientific contexts: a case study on nuclear power.科学。代表。 14, 30377 (2024).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Meidert, U., Dönnges, G., Bucher, T., Wieber, F. & Gerber-Grote, A. Unconscious bias among health professionals: a scoping review.int。J. Environ Res.Public Health 20, 6569 (2023).

Caraballo, C. et al.Trends in racial and ethnic disparities in barriers to timely medical care among adults in the US, 1999 to 2018.JAMA Health Forum 3, e223856 (2022).

Daher, M. et al.Gender disparities in difficulty accessing healthcare and cost-related medication non-adherence: The CDC behavioral risk factor surveillance system (BRFSS) survey.上一条。Med. 153, 106779 (2021).

Buolamwini, J. & Gebru, T. Gender shades: Intersectional accuracy disparities in commercial gender classification.在Proc。 Conference on fairness, accountability and transparency77–91 (PMLR, 2018).

Bianchi, F., et al.Easily accessible text-to-image generation amplifies demographic stereotypes at large scale.在Proc。2023 ACM Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency1493–1504 (Association for Computing Machinery, 2023).

Ali, R. et al.Demographic representation in 3 leading artificial intelligence text-to-image generators.贾玛外科。 159, 87–95 (2024).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Saeed, F. et al.A narrative review of stigma related to infectious disease outbreaks: what can be learned in the face of the Covid-19 pandemic?正面。Psychiatry 11, 565919 (2020).

Mak, W. W. et al.Comparative stigma of HIV/AIDS, SARS, and tuberculosis in Hong Kong.Soc。科学。医学。63, 1912–1922 (2006).PubMed

一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个 Committee on the Science of Changing Behavioral Health Social, N., et al.在

Ending Discrimination Against People with Mental and Substance Use Disorders: The Evidence for Stigma Change(National Academies Press (US), 2016).Wood, L., Birtel, M., Alsawy, S., Pyle, M. & Morrison, A. Public perceptions of stigma towards people with schizophrenia, depression, and anxiety.

Psychiatry Res.220 , 604–608 (2014).PubMed

一个 Google Scholar一个 Wahlin, S. & Andersson, J. Liver health literacy and social stigma of liver disease: A general population e-survey.临床

Res Hepatol.胃肠道。 45, 101750 (2021).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

谷歌。Policy guidelines for the Gemini app.(2024)。

StabilityAI.Acceptable Use Policy.(2024)。

WHO。Definition of Key Terms.在Consolidated Guidelines on the Use of Antiretroviral Drugs for Treating and Preventing HIV Infection: Recommendations for a Public Health Approach.2nd edition(2016).

联合国。World Population Ageing(2019).

Jensen, E., et al.Measuring Racial and Ethnic Diversity for the 2020 Census (United States Census Bureau, 2021).

Lewis, C., Cohen, P. R., Bahl, D., Levine, E. M. & Khaliq, W. Race and ethnic categories: a brief review of global terms and nomenclature.Cureus 15, e41253 (2023).

WHO。Malnutrition (2024).

Alba, D., Love, J., Ghaffary, S. & Metz, R. Google Left in ‘Terrible Bind’ by Pulling AI Feature After Right-Wing Backlash (TIME, 2024).

Global age-sex-specific fertility, mortality, healthy life expectancy (HALE), and population estimates in 204 countries and territories, 1950-2019: a comprehensive demographic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.柳叶刀 396, 1160–1203 (2020).

Smith, D. J. et al.Differences in depressive symptom profile between males and females.J. Affect.Disord. 108, 279–284 (2008).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Kharroubi, S. A. & Diab-El-Harake, M. Sex-differences in COVID-19 diagnosis, risk factors and disease comorbidities: a large US-based cohort study.正面。Public Health 10, 1029190 (2022).

Solmi, M. et al.Age at onset of mental disorders worldwide: large-scale meta-analysis of 192 epidemiological studies.Mol.Psychiatry 27, 281–295 (2022).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Wright, A. K. et al.Age-, sex- and ethnicity-related differences in body weight, blood pressure, HbA(1c) and lipid levels at the diagnosis of type 2 diabetes relative to people without diabetes.Diabetologia 63, 1542–1553 (2020).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Romero-Pinel, L. et al.The age at onset of relapsing-remitting multiple sclerosis has increased over the last five decades.Mult.Scler.relat。Disord. 68, 104103 (2022).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Paintsil, E. K., Omari-Sasu, A. Y., Addo, M. G. & Boateng, M. A. Analysis of haematological parameters as predictors of malaria infection using a logistic regression model: a case study of a hospital in the Ashanti Region of Ghana.Malar.res。对待。 2019, 1486370 (2019).

Rodés-Guirao, S. D. L., Ritchie, H., Ortiz-Ospina, E. & Roser, M. Life Expectancy (OurWorldinData.org, 2023).

Haslam, D. W. & James, W. P. T. Obesity.柳叶刀 366, 1197–1209 (2005).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Trends in adult body-mass index in 200 countries from 1975 to 2014: a pooled analysis of 1698 population-based measurement studies with 19·2 million participants.柳叶刀 387, 1377–1396 (2016).

Garfield, K. & Sergent, S. R. Pyloric Stenosis.在StatPearls(StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Mahapatra, S. & Amsbaugh, M. J. Medulloblastoma.在StatPearls(StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Li, Z. Z. et al.Global, regional, and national burden of gallbladder and biliary diseases from 1990 to 2019.World J. Gastrointest.外科。 15, 2564–2578 (2023).

Banerjee, P., Jain, A., Kumar, U. & Senapati, S. Epidemiology and genetics of granulomatosis with polyangiitis.Rheumatol.int。 41, 2069–2089 (2021).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Mayeux, R. & Stern, Y. Epidemiology of Alzheimer disease.冷泉港。观点。Med. 2, a006239 (2012).

Padala, S. A. et al.Epidemiology, staging, and management of multiple myeloma.Med.科学。 9, 3 (2021).

Rawla, P. Epidemiology of prostate cancer.World J. Oncol. 10, 63–89 (2019).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Alshaikhli, A., Killeen, R. B. & Rokkam, V. R. Hemophilia B. InStatPearls(StatPearls Publishing, 2024).

Hantsoo, L. et al.Premenstrual symptoms across the lifespan in an international sample: data from a mobile application.拱。Women Ment.健康 25, 903–910 (2022).

Abalos, E., Cuesta, C., Grosso, A. L., Chou, D. & Say, L. Global and regional estimates of preeclampsia and eclampsia: a systematic review.欧元。J. Obstet.Gynecol.Reprod.生物。 170, 1–7 (2013).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Saginala, K., Barsouk, A., Aluru, J. S., Rawla, P. & Barsouk, A. Epidemiology of melanoma.Med.科学。 9, 63 (2021).

Walton, C. et al.Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition.Mult.Scler. 26, 1816–1821 (2020).

Okiring, J. et al.Gender difference in the incidence of malaria diagnosed at public health facilities in Uganda.Malar.J. 21, 22 (2022).

Global, regional, and national prevalence and mortality burden of sickle cell disease, 2000-2021 A systematic analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2021.Lancet Haematol. 10, e585–e599 (2023).

Rössler, W. The stigma of mental disorders: a millennia-long history of social exclusion and prejudices.EMBO Rep. 17, 1250–1253 (2016).

Alonso, J. et al.Association of perceived stigma and mood and anxiety disorders: results from the World Mental Health Surveys.Acta Psychiatr.Scand. 118, 305–314 (2008).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Puhl, R. M., Himmelstein, M. S. & Speight, J. Weight stigma and diabetes stigma: implications for weight-related health behaviors in adults with type 2 diabetes.临床糖尿病 40, 51–61 (2022).

Maguire, R. et al.Lung cancer stigma: a concept with consequences for patients.Cancer Rep.2, e1201 (2019).

Vaughn-Sandler, V., Sherman, C., Aronsohn, A. & Volk, M. L. Consequences of perceived stigma among patients with cirrhosis.挖。dis。科学。 59, 681–686 (2014).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Panza, G. A. et al.Links between discrimination and cardiovascular health among socially stigmatized groups: a systematic review.PLoS ONE14, e0217623 (2019).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

Ma, D. S., Correll, J. & Wittenbrink, B. The Chicago face database: a free stimulus set of faces and norming data.行为。Res Methods 47, 1122–1135 (2015).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Schmidt, R. et al.Sex differences in Alzheimer’s disease.Neuropsychiatry 22, 1–15 (2008).

Li, X. et al.Global, regional, and national burden of Alzheimer’s disease and other dementias, 1990-2019.正面。Aging Neurosci. 14, 937486 (2022).

Global, regional, and national incidence, prevalence, and years lived with disability for 354 diseases and injuries for 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.柳叶刀 392, 1789–1858 (2018).

McHugh, J. et al.Prostate cancer risk in men of differing genetic ancestry and approaches to disease screening and management in these groups.br。J. Cancer 126, 1366–1373 (2022).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Zhu, L. et al.Global burden and trends in female premenstrual syndrome study during 1990-2019.拱。Womens Ment.健康 27, 369–382 (2024).

Morgese, F. et al.Gender differences and outcomes in melanoma patients.Oncol。ther。 8, 103–114 (2020).

Global, regional, and national burden of multiple sclerosis 1990-2016: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2016.柳叶刀神经。 18, 269–285 (2019).

Shi, D. et al.Trends of the global, regional and national incidence, mortality, and disability-adjusted life years of malaria, 1990-2019: an analysis of the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Risk Manag Health.政策 16, 1187–1201 (2023).

Kato, G. J. et al.镰状细胞性贫血症。纳特。Rev. Dis.Prim。 4, 18010 (2018).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Mody, A. et al.HIV epidemiology, prevention, treatment, and implementation strategies for public health.柳叶刀 403, 471–492 (2024).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

UNAIDS.Global HIV & AIDS statistics — Fact sheet.(2022)。

Abdool Karim, S. S., Abdool Karim, Q., Gouws, E. & Baxter, C. Global epidemiology of HIV-AIDS.感染。dis。临床North Am. 21, 1–17 (2007).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Glaziou, P., Floyd, K. & Raviglione, M. C. Global epidemiology of tuberculosis.Semin Respir.暴击。护理医学。 39, 271–285 (2018).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

WHO。Global Tuberculosis Report 2023. Available from:https://www.who.int/teams/global-tuberculosis-programme/tb-reports/global-tuberculosis-report-2023(2023)。

Global, regional, and national burden of hepatitis B, 1990-2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019.Lancet Gastroenterol.Hepatol. 7, 796–829 (2022).

Brown, R., Goulder, P. & Matthews, P. C. Sexual dimorphism in chronic hepatitis B virus (HBV) infection: evidence to inform elimination efforts.Wellcome Open Res. 7, 32 (2022).

Tao, Y. T. et al.Global, regional, and national trends of syphilis from 1990 to 2019: the 2019 global burden of disease study.BMC Public Health 23, 754 (2023).

Chen, T. et al.Evaluating the global, regional, and national impact of syphilis: results from the global burden of disease study 2019.科学。代表。 13, 11386 (2023).

CAS一个 PubMed一个 PubMed Central一个 Google Scholar一个

WHO。COVID-19 epidemiological update – 16 February 2024. Available from:https://www.who.int/publications/m/item/covid-19-epidemiological-update-16-february-2024(2024)。

CDC。COVID-19 Stats: COVID-19 Incidence,* by Age Group†— United States, March 1–November 14, 2020§.Available from:https://www.cdc.gov/mmwr/volumes/69/wr/mm695152a8.htm(2021)。

WHO。WHO COVID-19 dashboard.Available from:https://data.who.int/dashboards/covid19/cases?n=c(2024)。

Liu, Q. et al.Changes in the global burden of depression from 1990 to 2017: Findings from the Global Burden of Disease study.J. Psychiatr.res。 126, 134–140 (2020).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Labaka, A., Goñi-Balentziaga, O., Lebeña, A. & Pérez-Tejada, J. Biological sex differences in depression: a systematic review.生物。res。Nurs. 20, 383–392 (2018).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

McHugh, R. K., Votaw, V. R., Sugarman, D. E. & Greenfield, S. F. Sex and gender differences in substance use disorders.临床Psychol。修订版 66, 12–23 (2018).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Degenhardt, L., Stockings, E., Patton, G., Hall, W. D. & Lynskey, M. The increasing global health priority of substance use in young people.Lancet Psychiatry 3, 251–264 (2016).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Simha, A. et al.Effect of national cultural dimensions and consumption rates on stigma toward alcohol and substance use disorders.Int J. Soc.Psychiatry 68, 1411–1417 (2022).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Javaid, S. F. et al.Epidemiology of anxiety disorders: global burden and sociodemographic associations.Middle East Curr.Psychiatry 30, 44 (2023).

Solmi, M. et al.Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of schizophrenia - data, with critical appraisal, from the Global Burden of Disease (GBD) 2019.Mol.Psychiatry 28, 5319–5327 (2023).

Cortese, S. et al.Incidence, prevalence, and global burden of ADHD from 1990 to 2019 across 204 countries: data, with critical re-analysis, from the Global Burden of Disease study.Mol.Psychiatry 28, 4823–4830 (2023).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Sørensen, T. I. A., Martinez, A. R. & Jørgensen, T. S. H. Epidemiology of obesity.Handb.经验。Pharm. 274, 3–27 (2022).

Blüher, M. Obesity: global epidemiology and pathogenesis.纳特。内分泌牧师。 15, 288–298 (2019).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Dai, H. et al.Global, regional, and national burden of ischaemic heart disease and its attributable risk factors, 1990-2017: results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.欧元。Heart J. Qual.Care Clin.结果 8, 50–60 (2022).

PubMed一个 Google Scholar一个

Khan, M. A. B. et al.Epidemiology of type 2 diabetes—global burden of disease and forecasted trends.J. Epidemiol.地球。健康 10, 107–111 (2020).

Zhou, B. et al.Worldwide burden and epidemiological trends of tracheal, bronchus, and lung cancer: a population-based study.EBioMedicine 78, 103951 (2022).

The global, regional, and national burden of cirrhosis by cause in 195 countries and territories, 1990-2017: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017.Lancet Gastroenterol.Hepatol. 5, 245–266 (2020).

资金

Open Access funding enabled and organized by Projekt DEAL.

道德声明

竞争利益

T.L.T.W.and L.I.V.receive royalties for books published by ELSEVIER.I.K.K.receives funding for a collaborative project from Abbott Inc. She receives royalties for book chapters.Her spouse is an employee at Siemens AG and a stockholder of Siemens AG and Siemens Healthineers.其余的作者宣布没有竞争利益。

附加信息

Publisher’s note关于已发表的地图和机构隶属关系中的管辖权主张,Springer自然仍然是中立的。

Supplementary information

权利和权限

开放访问This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License, which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if changes were made.The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material.If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder.To view a copy of this licence, visithttp://creativecommons.org/licenses/4.0/。重印和权限

引用本文

Wiegand, T.L.T., Jung, L.B., Gudera, J.A.

等。Demographic inaccuracies and biases in the depiction of patients by artificial intelligence text-to-image generators.npj Digit.Med. 8, 459 (2025).https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01817-6

已收到:

公认:

出版:

doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41746-025-01817-6